What is enamel?

You might encounter the word ‘enamel’ when you brush your teeth, drive your car, take the train, or cook using your pots and pans. It covers your jewellery, decorates your glassware, coats road signs and insulates electrical wiring.

Enamel, seemingly, is everywhere. Or is it?

When people talk about enamel, they are actually often confusing several, very different, types of material. Tooth enamel is very different to enamel paint, which in turn is very different to porcelain or vitreous enamel, the type of enamel you’ll find on an antique object.

Quite simply, vitreous enamel is a mixture containing powdered, or ground, glass, which is then applied to the surface of a piece and fired. It has the hardness of metal but the delicacy of glass, and it’s colourful, slightly translucent and stunningly beautiful.

Indeed, this kind of enamel – the enamel you’ll encounter on an antique object – is a complex, precious and beautiful material which has a history stretching back thousands of years, and which requires an extremely high degree of skill and precision to use.

Many of the finest and most precious antique pieces in existence feature enamelled decorations: these include vases, jewellery, precious boxes, clock dials, frames, even furniture.

What does enamel look like?

Enamel is a smooth, hard, glass-like material which normally appears on antique pieces as a colourful, decorative exterior coating.

Chemically, enamel has a number of properties which make it especially valuable: it is unreactive, hard, easy to clean, resistant to burning and scratching, and does not lose its colour over time.

Gold, enamel, and diamond snuffbox by Jean-Marie Tiron. The plaque on the lid of the box is made from painted enamel. © Wmpearl via Wikimedia Commons

The best way to test if an antique piece is coated with enamel is to tap it (softly!) with your nails. It should sound like a particularly delicate, thin, metallic form of glass.

How is enamel made?

One important thing to remember about enamel is that it is a coating, not a base material. Enamel is too brittle on its own, and so it is most often used to cover and decorate metals: iron, copper, aluminium, silver, and gold.

The process of enamelling a metal involves forming a powdered glass paste and mixing it with various pigments to give it a colour. Cobalt oxide, for example, is the pigment which produces the colour blue.

The paste is then applied to the surface of the metal, and fired at a high temperature (normally around 1500 degrees Celsius).

There are a wide range of different ways enamel can be applied and fired, each of which gives a range of different effects. Some are as old as enamel itself, and date back thousands of years, while others have been discovered more recently.

The main techniques for enamelling, and how to identify them, are outlined below.

Cloisonné enamel

Cloisonné enamelling is the oldest and most highly regarded technique for producing decorative enamel ware.

The cloisonné technique, confusingly, actually predates enamel: its first known use was in Ancient Egypt in around 4000 BC for setting stones into jewellery.

‘Cloisonné’ refers to any decorative effect produced by applying fine wires to the surface of an object to form the outlines of shapes. These shapes are known as ‘cloisons’ and, in the cloisonné enamelling process, they are filled in by enamel paste which is then fired.

Chinese cloisonne enamel incense burner from the Ming Dynasty, c.1450-1550. Notice the gold outlines of the flower shapes: these are the 'cloisons' into which the coloured enamel paste is fired

Cloisonné enamel pieces are well-known for their beautiful, intricate, two-dimensional surface designs.

Champlevé enamel

Similar to cloisonné, champlevé enamelling is another old and highly revered technique.

Instead of forming shapes on a metal’s surface using wires, champlevé enamelling involves carving ‘pits’ into the actual surface of the metal into which enamel is poured.

The 'Becket' casket, in champleve enamel on copper, currently on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Notice how the exposed metal (the yellow / gold coloured parts) are slightly 'raised' above the enamel (blue and green). © Marie-Lan Nguyen via Wikimedia Commons

Guilloché enamel

Guilloché enamelling involves engraving an intricate pattern onto the surface of a material, and then covering the whole surface of the material in enamel paste before firing, giving the piece a stunning glossy, textured finish.

This technique is most commonly associated with the work of the Russian jeweller Fabergé, discussed below.

Plique-à-jour enamel

Plique-à-jour enamelling is one of the most complex and difficult techniques, similar to cloisonné in that it involves the application of enamel into shapes formed by wires. The difference is that, in plique a jour wares, the metal base or backing is dissolved or rubbed away, leaving a translucent panel of enamel.

This technique was perfected by Japanese craftsmen in the later 19th Century, before becoming popular in Russia and Scandanavia.

Plique-a-jour enamel bowl by acclaimed Japanese craftsman Namikawa Sosuke, for the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900. Note how there is no backing, and the light shines through the bowl like a stained glass piece. © Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

Basse-taille enamel

In the technique of basse-taille enamelling, the base metal is cast into a low relief pattern, and translucent enamel poured into it. The resultant surface is flat, but reflects the light to show the relief beneath it.

The Royal Gold Cup at the British Museum, shown below, is perhaps the prime example of the use of this technique. It was made for the French Royal Family in the 14th Century and later belonged to both English and Spanish monarchies.

Detail from the Royal Gold Cup on display at the British Museum, showing the baisse-taille enamel work. © BabelStone via Wikimedia Commons

Ronde-bosse enamel

Most enamelling techniques involve applying enamel to the surface of a metal. The ronde-bosse (meaning ‘in the round’) technique, however, involves the application of enamel around a metal core. It is also sometimes described as encrusted enamel.

Whilst in other enamelling techniques, enamel is painted, or applied only to the front surface of a metal object; in ronde-bosse enamelling, the entire object is effectively 'dipped' in enamel paste before being fired.

En résille enamel

Finally, the en résille technique is an extremely rare and highly intricate form of enamelling, involving etching a design into glass and then lining the grooves with enamel-coated gold foil. It was first used in 17th Century France, but underwent a revival in the mid-20th Century, led by the famed American metalworker, Margaret Craver.

Antique enamel: what was it used for?

So the production of artistic enamel is a complex, sophisticated process, requiring a high level of skill to execute. And yet it has been in use for thousands of years.

The first known example of vitreous enamel ware is a set of rings found in Cyprus which, incredibly, date from the 13th Century BC. And a number of other ancient cultures in the first millennium BC also made use of enamel products, mostly using primitive cloisonné techniques. These included ancient Greek, Chinese, Celtic and Georgian civilizations.

Ancient Celtic enamelled bronze plaque from the 1st Century AD, probably used for equestrian or military equipment, held at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge, UK. © Gun Powder Ma via Wikimedia Commons

It was not, however, until the Middle Ages that artisans and craftsmen started to experiment widely with enamel, producing some of the most complex and delicate pieces in existence. The most important periods and centres for enamel production throughout history are outlined below.

Byzantine cloisonné enamel

The first medieval civilisation to produce valuable enamel pieces was the Byzantine Empire (285 - 1453 AD), the direct descendants of the ancient Eastern Roman Empire in modern-day Greece and Turkey.

The Byzantines in particular perfected the cloisonné technique, by soldering thin strips of gold onto metal backings to form the cloisons into which the enamel would the applied. There is also some surviving evidence of Byzantine plique-à-jour and champlevé enamelling.

Byzantine enamel wares tended to come in the form of precious and religious objects, such as icons, panels, and crowns, as well as staurothekes, relic boxes which supposedly contained fragments of the Cross on which Jesus died.

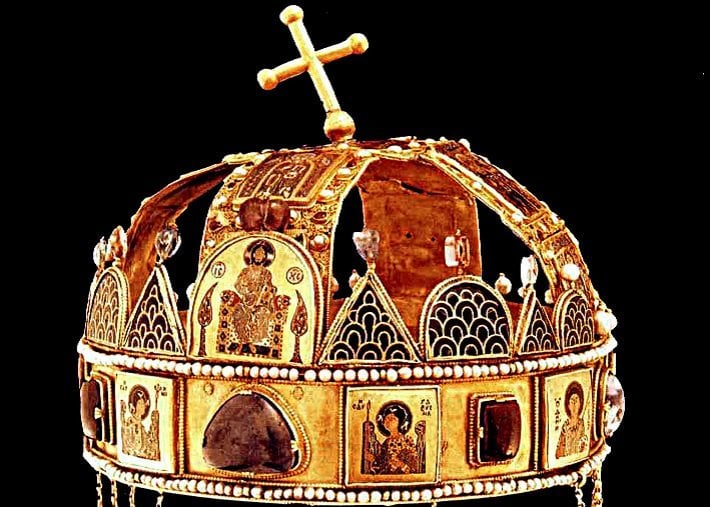

Perhaps the most famous surviving example of Byzantine enamel work is St Stephen’s Crown, which is still used today as the crown of the King of Hungary.

The Holy Crown of Hungary, also known as St Stephen's crown, gold with Byzantine cloisonne enamel highlights

Made by goldsmiths and enamellers in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) in around 1070 AD, the large gold crown was presented as a gift to King Geza I of Hungary by the Byzantine Emperor Michael VII Doukas and features delicately enamelled depictions of both men.

Limoges enamel in the Middle Ages

The know-how of the Byzantine enamellers gradually spread around Europe and Asia and created several new centres of enamel production during the Middle Ages.

Perhaps the most important of these was the French town of Limoges, which quickly became Europe’s leading enamel production hub between the 12th and 16th Centuries. Fourteenth-century Limoges was to enamel what nineteenth-century Sevres was to porcelain.

Champlevé enamel wares were associated with the early period of Limoges’ production: the base metal was mostly copper, but a few exceptional pieces used silver and gold.

Limoges enamel was used to decorate candlesticks (attesting to the importance of lighting in the Middle ages), book covers (known as ‘treasure bindings’), the tombs of the rich, mirror backs, dishes, and caskets.

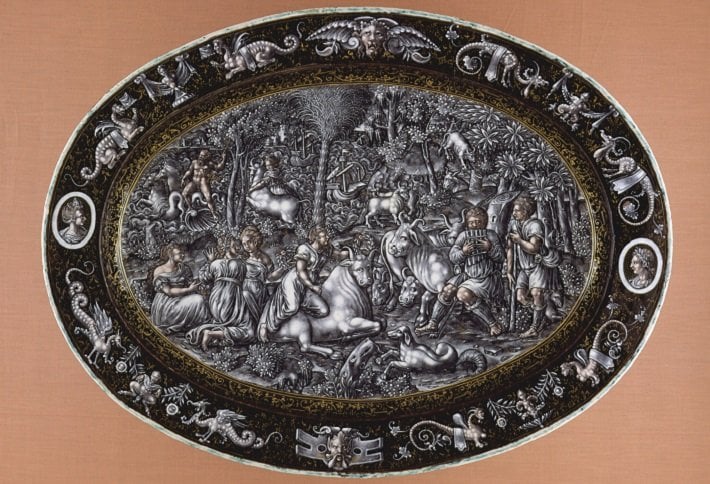

A 16th Century Limoges painted enamel dish, depicting the mythological scene of 'The Rape of Europa'

At the height of the Renaissance in the 16th Century, Limoges’s craftsmen also started producing painted enamel plaques and triptychs in the popular Mannerist style.

Production at Limoges fell into decline after the 17th Century, largely owing to a lack of patronage, but there was something of a revival in the latter 19th Century, which largely coincided with the development of the Art Nouveau style.

Persian Meenakari enamelling

At roughly the same time that Limoges enamel was dominant in Europe, a new decorative style took off in Persia (modern-day Iran). It was known as Meenakari, a word which refers to the blue colour of many of the pieces.

Meenakari is a colourful style of cloisonné enamel, applied most often to small, delicate pieces of jewellery, precious boxes and dining sets.

It’s difficult to find reliable information about the origins of Meenakari, but we know that it was popular during the era of the Safavid Empire in Persia (1501-1736 AD), and soon spread to India. Today it is most commonly associated with Indian jewellery and objets d’art.

Detail from a modern day Iranian Meenakari plate

Chinese Canton enamel

Unlike porcelain - which was invented in China and copied by Europeans - Chinese artisans learned enamelling from Europe, and the Canton region became a centre for enamel production in China.

Material evidence suggests that the cloisonné technique had reached China by the 13th Century, having arrived with French travellers to the region. These travellers had brought Limoges enamel wares with them, which had so impressed their Chinese hosts that they began attempting to create their own cloisonné pieces.

Despite its beginnings in the Middle Ages, it wasn't until the 18th Century that Chinese Canton enamel reached its full potential. The pieces produced during this period – stunning vases, jardinieres and tea sets – quickly found a market not only in China but across the Western world too.

Cantonese enamel objects, together with porcelain products made in the region, can often be identified by their colour palette of pinks (known as famille rose) and greens (known as famille verte).

Detail from an 18th Century Chinese Canton enamel jug. Notice the famille rose and famille verte colours on the surface

Viennese enamel in the 19th Century

Some of the most fine and detailed enamel objects ever produced derive from Vienna, which as a city largely filled the void left by the decline of Limoges to become Europe’s leading centre of enamel production in the 19th Century.

The Viennese artisans created enamel relics in a very distinctive style, and Viennese enamel objects are identifiable by their pink-centric colour palettes, and the use of painted court and landscape scenes.

Important enamel artists operating in Vienna during this period include Hermann Ratzersdorfer and Hermann Bohm, both of whom specialised in Renaissance style enamelled silver pieces of jewellery and tableware.

Detail from a 19th Century Viennese enamel and silver ship by Hermann Bohm, one of Vienna's finest craftsmen.

Japanese Meiji period enamel

The Meiji period of the late 19th Century in Japan is often known as the ‘Golden Age’ of cloisonné enamelling, and many exceptional pieces – vases, teapots, caskets – found their way into Europe, where they became highly desirable.

Most Japanese enamel production in the Meiji period centred on the town of Toshima, under the leadership of important artisan Tsukamoto Kaisuke (1828-1887).

It was in Toshima at the end of the 19th Century, and later in Tokyo, that Japanese makers started to experiment with new, complex techniques, including plique-à-jour (called shōtai-jippō in Japanese) and ronde-bosse.

Russian enamel and the House of Fabergé

No discussion of the history of enamel could be complete without mentioning Carl Faberge, the French goldsmith and jeweller who achieved worldwide fame for his delicate, luxurious and beautiful designs.

Although his most famous pieces were the Imperial Easter Eggs, made as gifts for the wife of Tsar Alexander III, Faberge was also renowned for items of jewellery and objets d’art.

Faberge used enamels in nearly all of his most precious pieces, including as the ‘shell’ for the Imperial Easter Eggs. The guilloché enamel technique was particularly associated with Faberge, and with later Russian objects made in the Faberge style.

Faberge-style cigarette box in green guilloché enamel

What is enamel used for now?

As the 20th Century progressed, manufacturers found ways of producing enamel on a mass scale, giving the material a whole range of new uses and purposes, outside of the artistic. This industrial form of enamel is normally fired at much lower temperatures than artistic enamel, and is therefore slightly different in composition.

It was thanks to this development that industrial enamels now coat the surfaces of cookware, home appliances, water heaters, bathtubs, toilets and laboratory equipment, not to mention road signs, whiteboards and outdoor advertisements.

So in the 20th Century enamel became a material of mass industry at the same time as remaining a material of skilled artisanry. It was a material of mundanity as well as a material of value. It was the material of bathtubs as well as the material of jewellery boxes.

It was, in short, something of a paradox.

And yet, enamel’s banal cameos in everyday life did not, and do not, detract from its desirability as an artistic material. Enamelled pieces of decorative art, especially antique pieces, remain highly sought after and extremely valuable.

Perhaps this is because enamel has always been about something more than itself. It has been about celebrating a tradition of fine craftsmanship, skill, and, ultimately, the pursuit of beauty.