We live today in an empire of glass, one which stretches from the tallest skyscraper to the smallest paperweight.

In every aspect of our life we are submissive to its seemingly infinite applications: we rely on it to build, to eat and drink, and even to see.

Glass, then, has a peculiar place in human history. We have relied on it for roughly 5000 years. And yet for most of that time, it was extraordinary difficult to make.

Indeed, even today the act of producing a sheet of glass from mere grains of sand seems like a kind of alchemy, a form of magic. The power to make glass was, since the beginning of human civilization, the power to transform nature into something more than itself.

What is glass and how is it made?

Most of us would be able to recognise glass if we saw it – it’s a solid material which is often (but not always!) transparent. It’s smooth to touch, non-malleable and can be moulded into any shape.

Unfortunately, though, at the chemical level, there’s no generally accepted definition for what glass is. Glasses can be made from a range of different combinations of ingredients, and each possesses subtly different qualities.

Generally, however, the main component of glass is a mineral compound known as silica (also called silicon dioxide or quartz). Silica is most commonly found in sand, which until fairly recently was used as the main ingredient in glassmaking.

To make glass, silica is combined with a range of different ingredients and then fired. The most common type of glass used today – and throughout its long history – is known as soda-lime glass, the type of glass that is clear and colourless to the naked eye.

Soda-lime glass production involves mixing together silica with ‘soda’ or sodium carbonate, and ‘lime’, or calcium oxide, before heating them together in a furnace at temperatures of around 1320 degrees Celsius. The molten mixture produced as a result is then worked into a shape and left to cool, producing solid glass.

A craftsman in his workshop pulling a length of molten glass into a shape. © Bentaylor13413 via Wikimedia Commons

In this process soda acts as a ‘flux’, an ingredient used to lower the overall temperature needed to produce molten glass, and lime as a ‘stabilizer’, an ingredient used to prevent the mixture from dissolving in water.

As you might expect, this basic recipe for glass production has varied quite considerably over the extremely long period that humans have been making glass. A number of different ingredients can be added to the mixture, all of which can produce different effects.

For example, the addition of different metallic salts to the process can give glass different colours; while the addition of lead oxide (a technique which results in ‘crystal’ glass) can increase the refractivity, and therefore the brilliance, of glass.

A history of glass

There is, then, no one single ‘right’ way to make glass.

Different techniques have been employed by different civilizations at different points in world history for different reasons, producing a wide range of different glass products.

Despite this wide variation in glassmaking techniques, glass as a material has been fairly consistently integral to human society, in the production of vessels (cups, bottles, vases), architectural features (windows), and other decorative pieces.

Indeed it’s perhaps because of, not despite, the vast possibilities that glass offers in terms of shape and colour that it has, for centuries, been thought of as an artistic and luxury material on a par with precious metals, gemstones and porcelain.

When was glass first made?

The first recorded instances of glass-like materials date as far back as the Stone Age (up to 3 million years ago!), when the naturally-occurring glasslike volcanic material obsidian would have been used by our prehistoric ancestors as sharp tools.

The process of glassmaking, however, is relatively newer, and can be traced back to and the civilizations of Ancient Syria, Egypt and Mesopotamia. It’s unclear which of these was the ‘first’ to start making glass, but glass objects from around 2500 BC have been found in all three regions.

These glass objects were largely decorative pieces – including cups, vases, and small plaques. These early pieces were not clear as we might expect, but vividly coloured, due to the impurities in the sand used to make up the glass mixture.

By the 9th Century BC techniques for producing colourless glass were developed in Syria, but soon afterwards glass production appears to have fallen into decline, to be revived once more in the civilization of Ancient Rome.

Roman glass and the discovery of glassblowing

Collection of Roman glassware from the 2nd Century AD, on display at the Musée Saint-Remi à Reims, Marne, France

Roman glass had been around for as long as Roman civilization itself: that is, since roughly the 8th Century BC. These early pieces were largely copies of Greek pieces, using Greek techniques.

These pieces served as vessels and containers, but were also used for more strictly artistic ends such as mosaic tiles.

Roman glass, however, only achieved true distinction in around the 1st Century BC, when craftsmen in the regions of the Roman Empire known as Syria and Judea (modern day Syria, Lebanon and Israel/Palestine) developed a revolutionary new glassmaking technique, one which is still widely practised today: glassblowing.

Glassblowing relied on a simple discovery: if you blow cool air into an amount of molten glass, it will start to inflate like a bubble. Mastering this technique meant that craftsmen could create any number of shapes in fairly quick time.

It’s difficult to understate quite how revolutionary this discovery was. Before the advent of glassblowing, artisans would form molten glass into shapes by wrapping it around a core, or by pouring it into a mould.

This was a time-consuming process, which did not always produce satisfactory results: the resulting shape would need to be painstakingly ground and polished before it could be finished.

Glassblowing, on the other hand, was a much speedier process, and one which used less glass to make the final product: glassmakers could, then, make more pieces and at much lower cost.

Once the technique had been discovered, it spread rapidly: by the 3rd Century AD there were important workshops all over Italy, Cyprus, Egypt and even as far as the Swiss Alps.

The word glass itself comes from this late Roman period, originating in the late-Latin/Germanic word glesum.

Glass in the Middle Ages

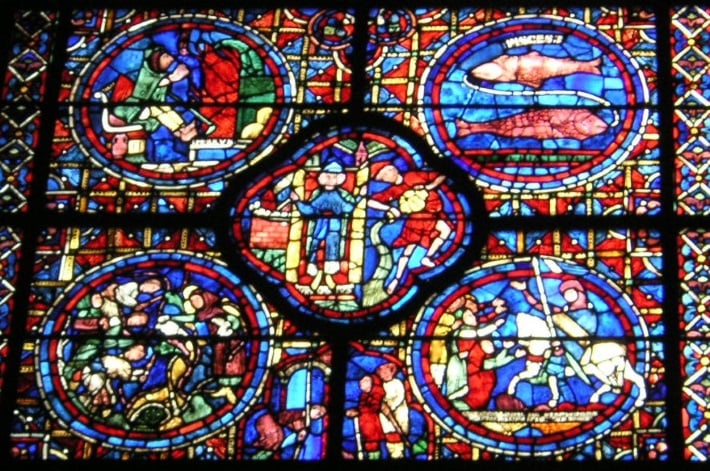

Stained glass window at Chartres Cathedral in France. Most of its 13th Century windows remain in tact.

In Europe, there appears to have been something of a decline in glass production after the fall of the Roman Empire. After the 5th Century glass, where it was seen in Europe, was largely imported from the Islamic world, at that time the leading centre of glass production in the world.

From around the 10th Century, however, there was something of a resurgence in European glass production. This was the first age of the stained-glass window, a new architectural feature which became heavily associated with the contemporary Romanesque and Gothic art styles.

Early examples of impressive stained-glass windows include those at the Basilica of St Denis (completed in 1144) and Chartres Cathedral (constructed between 1194 and 1220), both in France, and both seen as masterpieces of Romanesque architecture.

This resurgence of glass production in Europe led to the establishment of several new centres of glassmaking. Two of these, perhaps the most renowned even today, were the regions of Murano near Venice, and Bohemia in modern-day Czech Republic.

Murano glass is today synonymous with the finest luxury glassware. Amazingly, the glass workshops in Murano have been in operation since 1291, when they were relocated there from Venice following a devastating fire in the city.

Murano glass became highly revered in the Middle Ages, not least due to the quality of the sand on the island which allowed them to produce glass with few impurities.

In the 15th and 16th Centuries, craftsmen in Murano began to experiment with novel techniques for producing artistic and decorative glassware.

Techniques for enamelling (fusing coloured glass frit to the surface of a piece) and gilding (fusing ground gold to a piece), thought lost since the age of the Ancient Syrians in the 9th Century BC, were reintroduced by the Murano glassblowers.

Perhaps the most important innovation of the Murano glassblowers was their perfection of a technique to produce a completely clear, colourless glass, which they called ‘cristallo’, after the gemstone rock crystal.

Glassmakers in Bohemia also began production of luxury glassware from around 1250, and discovered, independently of Murano, the technique for making colourless glass.

Despite its origins in the High Middle Ages, the Golden Age of Bohemian glass came in the 17th Century, when Bohemian glassblowers were the pioneers of the Baroque style in glassware.

Artisans, and particularly the workshop of Caspar Lehmann (fl. early 17th Century) were especially revered for the innovative engraving and cutting techniques they developed, producing some exceptionally intricate pieces for important clients all over Europe.

Glass in the Age of Decoration

Crystal chandeliers in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles, perhaps the greatest achievement of the Age of Decoration

Murano and Bohemian glassware also became integral to the so called ‘Age of Decoration’ in the 18th Century. This was the age in which demand for luxury goods among Europe’s royalty and nobility soared, and artisans began to experiment with ever more complex techniques.

The 18th Century Bohemian glass workshops developed, for example, a technique which became known as ‘crystallo ceramie’, involving embedding a decorative ceramic object inside a piece of glass. This effect was most commonly employed in the production of paperweights, decanters, bottle stoppers and perfume bottles.

Perhaps the great developments of the Age of Decoration, however, took place in neither Bohemia nor Murano, but in England.

English glassmakers would emerge, by the middle of the 18th Century, as one of the foremost powers in luxury glass production in Europe.

From 1725, for example, English makers had started to produce so-called ‘cut glass’, glassware produced by cutting and grinding large pieces of solid glass and crystal into new shapes, and faceting the surface of pieces to create a ‘prismatic’ effect which allowed the glass to reflect and radiate light.

Of course, the greatest achievement of the English glassmakers was the discovery, in the 1670s, of the technique for making so-called ‘crystal’ glass. English ‘crystal’ was superior to Venetian ‘cristallo’ because it was more durable and easier to decorate.

What the English manufacturers understood better than any of their counterparts was that the appeal of glass lay in its ability to reflect, refract, and radiate light. Crystal could do all of these things, and more brilliantly than any other form of glass.

It’s not surprising, then, that in the 18th Century, glass – and crystal in particular – was widely used in the production of lighting fixtures. Crystal candlesticks and chandeliers became enormously popular among Europe’s elite precisely for the sparkle and brilliance they added to a room.

Crystal was so popular that by the beginning of the 19th Century, nearly all of Europe’s glassworks were producing elaborate pieces of tableware, vases, and lighting in crystal and cut glass.

One important new player in crystal glass production was the famed Baccarat company, the producers of some of the finest 19th Century glass pieces.

What is the difference between crystal and glass?

Top of a cut and engraved crystal wine glass. Note the distinctive, and rather beautiful, way that the decorations catch the light.

The major difference between ‘crystal’ as produced in 18th Century England, and other forms of soda-lime glass, was the addition of lead oxide to the glass mixture.

In today’s terms, the European Union classes any glassware with over 10% lead content as ‘crystal’ or ‘lead crystal’, and anything with over 30% lead as ‘high-lead crystal’.

It is this lead content which gives crystal its distinctive prismatic lustre: if caught by light in the right way, a piece of crystal will cast a spectrum – or rainbow – of colours around a room.

Additionally, lead crystal is heavier, thicker and more durable than standard glass – a feature which also makes it easier to engrave, grind and cut. It’s for this reason that crystal in the 18th Century was generally used for larger items, such as windows and grand chandeliers.

Industrial glass in the 19th Century

Photograph of the interior of the Crystal Palace in 1851, shortly before the Great Exhibition. One of the most notable featuers of the building was that a number of trees were planted inside it, as shown in this photograph.

The 19th Century was also the era of experimentation in glassmaking, assisted by the technological advances of the coming Industrial Revolution. It was also an era of competition among established – and emerging – glassmaking centres to develop ever-more complex and elaborate techniques.

Perhaps the greatest technological feat of glassmaking of the whole century was London’s Crystal Palace, finished in 1851 for the Great Exhibition of that year. The Crystal Palace was a vast structure, 564 metres long and 39 metres high, made out of sheets of glass totalling 84,000 square metres.

The sheets of glass used in the production were made using the novel ‘Rolled Plate’ method: that is, rolling out large quantities of molten glass until flat before cooling. This is why this type of glass is known as ‘plate’ glass.

Millefiori glass

A Rococo style millefiori Murano glass chandelier at the Ca' Rezzonico Palace in Venice. © Dider Descouens via Wikimedia Commons

At the same time in Venice, the Murano makers were developing their famous ‘millefiori’ technique, the form of glass for which they are perhaps best known.

Millefiori involving pouring layers of differently coloured glass around a steel rod to form a concentric design. The rod is then pulled thin (to form a piece known as a ‘murrine’), and the process is repeated until the final rod is cut and placed in a mould with other murrines to form the final shape.

Millefiori (literally meaning ‘thousand flowers’) pieces are extremely colourful, intricate pieces. The technique was most spectacularly employed on Murano’s famous chandelier on display at the Ca' Rezzonico in Venice, an intricate, flamboyant, Rococo-style masterpiece.

Cameo and opaline glass

But as well as pioneering new methods of glass production, glassmakers in the 19th Century looked increasingly to the past for inspiration.

Indeed, the 19th Century saw revivals in a number of older glassmaking techniques, including the Roman ‘cameo’ method (involving applying successive layers of glass to form a relief pattern), which was most famously employed on the 1st Century AD Portland Vase.

Front and back view of the famed Portland Vase, on display at the British Museum. The exterior decorations were created by applying successive layers of molten glass to form a relief decoration, which is then left to cool. This technique, known as 'cameo' glass, was revived in the 19th Century. © Marie-Lan Nguyen via Wikimedia Commons

Similarly, Baccarat in France was responsible for reviving the 16th Century Venetian technique of ‘milk glass’, that is, coloured opaque glass which could then be enamelled with designs. This was known, in the 19th Century, as opaline glass, after the gemstone opal which it was supposed to imitate.

Opaline glass was hugely popular in the period, particularly since it could come in a wide range of colours and offered a wide range of possibilities for decoration.

Art Nouveau glass

The iconic 'Tiffany Lamp', with stained glass shade

These revivals of older techniques were particularly associated with the Art Nouveau movement, which flourished in Europe in the late 19th Century.

In the Art Nouveau period, glassmaking was seen as an elite art form on a par with painting, sculpture, and jewellery.

Important glassmakers in this period were the French artists Emile Gallé (1846-1904), Jean Daum (1825–1885), and René Lalique (1860-1945) revered for their lush colour palettes, innovative forms and beautiful decoration.

Bohemia had seen a small decline in glass production during the 19th Century, but the industry was revived during the Art Nouveau period under Ludwig Lobmeyr (1829-1917), who founded a glass studio, known as J & L Lobmeyr, at Kamenický Šenov.

These Art Nouveau glassmakers also made a huge range of glass pieces, ranging from jewellery to vases to lamps, all using innovative techniques such as acid-etching and wheel engraving.

Perhaps the most iconic Art Nouveau glass piece is the Tiffany lamp, designed by American artist Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933), and pictured above.

Tiffany – founder of the eponymous world-famous jewellery brand – pioneered a new form of glass, which he called ‘lustred glass’. Tiffany lustred glass was made with the addition of metallic pigments, which gave his pieces a distinctive iridescent, metallic sheen.

Glass in the modern era

What was interesting about glassmaking in the Art Nouveau period was that artists were seemingly as comfortable using traditional, hand-making techniques as they were with mass production in large factories.

Lalique, for example, began producing Art Deco-style glass pieces on a large scale from the 1920s.

This uneasy tension between manual and machine techniques was one which continued into the 20th Century and beyond, particularly with new industrial developments.

English industrialist Michael Owen, for example, invented an automatic bottle blowing machine in 1903, while Sir Alastair Pilkington (of Pilkington’s Glassworks in St Helens, England) developed his revolutionary ‘float glass’ method in the 1950s.

The ‘float glass’ method, which allows for large sheets of glass to be produced on a machine conveyor quickly and cheaply, is the method by which 90% of flat plate glass is produced today.

It was perhaps as a reaction to these new methods of mass production that the artists Harvey Littleton and Dominick Labino in 1962 established the ‘studio glass’ movement.

This movement, based in Toledo in Spain, aimed to promote the revival of small glass workshops, and, ultimately, of glassmaking as a form of art. The studio glass artists in particular encouraged the technique of ‘free blowing’, or glassblowing without a mould, as an expression of maximum artistic freedom and total creativity.

It was the ideas of this movement which inspired famous contemporary glass artist Dale Chihuly, whose large scale glass sculptures and installations can be found all over the globe.

Dale Chihuly floral glass installation at Kew Gardens, London, England

Chihuly’s work is perhaps the ultimate symbol of how far glassmaking has come since its Bronze Age origins. Glassmaking is and always has been an enormously diverse art.

And yet, whether ancient or contemporary, glass has – and has always had – the power to evoke wonder and awe. Purity, simplicity, clarity and timelessness – these are the universal themes of the art of glass.