Visitors to the Great Exhibitions of the 19th Century often wrote of being dazzled by the monumental glass structures, fountains, lighting fixtures and sculptures that they encountered – whether Joseph Paxton’s vast Crystal Palace, or F. & C. Osler’s monumental chandeliers.

Of all the glassware on display at the exhibitions, however, it was the French firm Baccarat’s which most consistently impressed contemporary observers. Their showings in 1855, 1867 and 1878 in particular caught the attention of important artistic patrons from all over the globe, from Portugal to Japan, and from America to India.

By the second half of the 19th Century, the company had established itself as Europe’s leading crystal glass manufacturer. Consistently praised for their timeless design, Baccarat pieces from this era are still today widely coveted.

What is Baccarat crystal?

The Baccarat company is one of France’s oldest and most established glass-working factories, and is still in operation today.

As well as producing spectacular display pieces for exhibition, Baccarat also made glass products for the wider market. By the start of the 20th Century, ownership of a set of ‘Baccarat crystal’ glasses was a symbol of wealth and refined taste.

And although it was Baccarat’s crystal glassware – perfectly clear, lustrous works of heavy, lead-based glass – which was (and is) their most sought-after product, in the 19th Century Baccarat made a wide variety of different types of glass, including opaline, millefiori and cristallo ceramie works.

How is Baccarat crystal made?

Baccarat crystal glass is made, like any other glass, by adding lead oxide to a mixture containing silica, a ‘flux’ such as soda (sodium carbonate) and a ‘stabiliser’ such as lime (calcium oxide).

One of Baccarat’s great innovations in the 19th Century was to devise a method for producing an even clearer, more brilliant crystal glass by adding nickel oxide to the mixture.

The raw ingredients are then heated together in furnaces which reach temperatures of around 1500 degrees Celsius. These furnaces take up to a month to get up to full heat, and so they are rarely left unheated.

The molten glass is then taken out of the furnace and blown or pulled into a shape. Normally this will be done with the use of a mould. Once the component shapes of a piece of glass have been created, they will then be put back into the furnace so that they fuse together.

After the finished piece has formed and cooled, it will then need to be decorated. Baccarat glasses are sometimes gilded, or applied with gold powder which is fused onto the surface of the glass.

Very often Baccarat glassware will be engraved. This is achieved by cutting a pattern into the glass, either with a stone or copper grindstone, or with acid.

Acid engraving involves covering the glass in bitumen, a tough tar-like material, to show the negative of the intended pattern. The glass is then dipped in acid which cuts away at the uncovered part. The bitumen is then washed off and the object polished.

A history of Baccarat glass

Aerial view of the town of Baccarat. © Sebastien Beaujard via Wikimedia Commons

Baccarat was founded in 1764 by King Louis XV in the town of Baccarat in the Lorraine region of Eastern France.

Baccarat was not France’s first glass workshop: there had also been a long-running history of glass production in the town of St Louis, also in Lorraine.

The first head of the Baccarat factory in the mid-18th Century was the-then Bishop of Orléans, Cardinal Louis-Joseph de Laval-Montmorency, eager to found a prestigious artistic workshop in his diocese.

Baccarat’s early production consisted of windows, mirrors, and items of tableware. It was not until the 19th Century that the factory’s production would broaden significantly, in both style and techniques.

Baccarat in the 19th Century

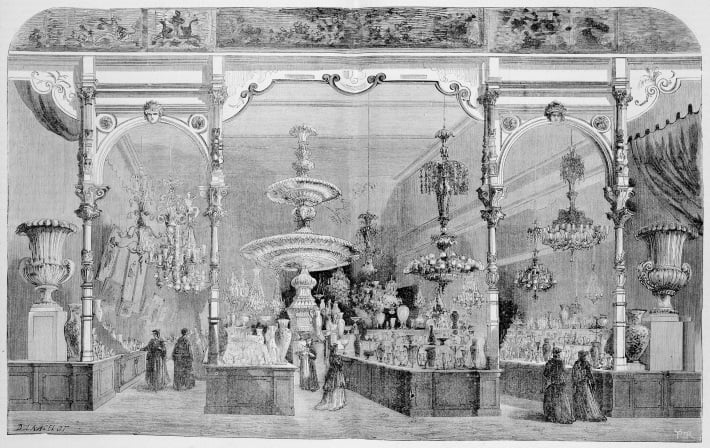

Baccarat's display at the 1867 Paris Exposition Universelle. Note the monumental crystal fountain in the centre of the display.

The period around the turn of the 19th Century had been a difficult time for the factory, owing to the French Revolution of 1789 and the subsequent period of war, Empire and invasion.

It was when the factory was acquired by a Belgian entrepreneur named Aimé-Gabriel d’Artigues that Baccarat’s fortunes turned. In 1816 Baccarat began production of fine lead crystal, using the techniques which had been developed by the English glassmakers of the later 18th Century.

It was at this point also that the firm was renamed as the Compagnie des Cristalleries de Baccarat, and, significantly, the period in which it received its first royal commission.

The firm’s work had been exhibited annually at the National Exhibition of Industrial Products from 1823, and had caught the eye of the restored Bourbon monarch, Charles X.

In 1828 Charles X visited the factory and was presented with two glass vases, a ewer, a tea service and a water set. These impressed him so much that he commissioned an extensive glass dinner service for the Tuileries Palace.

It was this visit which would start a long line of French monarchs, Emperors and heads of state commissioning glassware from the Baccarat factory. In the mid-19th Century, both King Louis-Philippe and the Emperor Napoleon III would become important customers of the factory.

At the 1855 Exposition Universelle in Paris, Baccarat won its first gold medal for a pair of monumental, 90-light standing candelabra.

It would go on to win more medals at the 1867 fair in Paris, where it exhibited a 24-foot tall glass fountain; and in 1878 where it displayed a glass ‘Temple of Mercury’ which contained a monumental sculpture of the Roman god.

Baccarat abroad

Baccarat chandelier and crystal balustrade in the Dolmbahce Palace, Istanbul. © Peace01234 via Wikimedia Commons

Baccarat’s strong showings at the Great Exhibitions of the 19th Century would earn it admirers and customers from further afield, including in Ottoman Turkey, Portugal, Japan, and India.

One of Baccarat’s great successes in the later 19th Century was the furnishings it provided for the Dolmbahce Palace, residence of the Ottoman Sultan in Istanbul.

Several monumental Baccarat crystal chandeliers were built for the palace, including the famous one which hangs above the so-called ‘Crystal Staircase’ in the Palace’s entranceway, pictured above. The staircase’s balustrades are also made from Baccarat crystal.

In the 1880s, Baccarat opened a new showroom in Bombay, as a reflection of the growing demand in Asia for its work.

Being brought into contact with the rest of the world also influenced the Baccarat company’s own designs, and it started to incorporate elements taken from Chinese, Japanese and Islamic art into its work.

Production at Baccarat continued into the 20th Century, and the factory opened new showrooms in America. In the 1990s, Baccarat began making jewellery and perfume as well as glass. Today it continues to operate as a luxury glass manufacturer.

How is Baccarat crystal marked and signed?

Baccarat's mark, which it provided as a paper label with piece from the 1860s, and started engraving on pieces made after 1936.

Unlike the great porcelain manufacturers of the 19th Century, Baccarat did not have a defined system for marking its pieces when it was first founded.

Some of its early paperweights (made between the years 1846 and 1849) were stamped with the letter ‘B’ followed by the year date.

But it was only as late as 1860 that Baccarat began to adopt any kind of trademark at all, and even then this took the form of a paper label attached to the product. Post-1860 items with their original paper labels are now extremely rare.

The paper label contained the mark that Baccarat would use for much of the rest of the 19th and 20th Centuries: a circular seal containing a decanter, with a cup and wine glass either side.

It was only as late as the 1930s that Baccarat began to engrave its mark on the glass, instead of providing a paper label.

Nowadays, Baccarat pieces contain a scripted laser-etched mark which reads Baccarat.

Baccarat glassware

Because Baccarat has been around for such a long time – over 250 years now – the range of its products, in both decorative style and technique, is extremely wide.

Below is a run-through of some of the company’s most famous and elaborate pieces from its history. Most of these were made in the 19th Century, when Baccarat was receiving its most important commissions from its clients.

Baccarat tableware and stemware

Baccarat crystal centrepiece and furniture at the Baccarat Museum, Paris

It was to design table services and drinkware that Baccarat was first commissioned by the French crown.

One of its more famous designs was its 1867 ‘Jusivy’ table service, originally made for the Exposition Universelle in the same year. After the exhibition, the service was moved to the Elysée Palace in Paris, now the official residence of the President of France, where it now resides.

Baccarat was also responsible, in 1841, for designing one of the most iconic wine glasses of the 19th Century, the Harcourt glass.

First commissioned by King Louis-Philippe of France, the thick, short-stemmed glass was immediately prized for its distinctive prismatic lustre, an iridescence-like effect of reflecting a range of colours depending on its position relative to a light source.

Baccarat vases

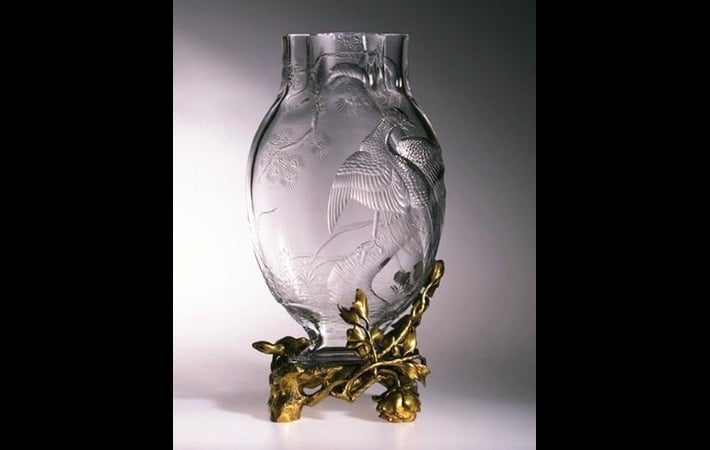

Art Nouveau era glass vase by Baccarat, 1890-1900, on display at the V&A in London. © Victoria and Albert Museum

Baccarat also produced a variety of designs for glass vases in the 19th Century: many were part of important commissions, while many more were produced for sale.

Baccarat’s crystal vases were highly prized objects. The above example, on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum, is one of the company’s late 19th Century creations. It has been designed to imitate Chinese rock crystal carvings in its form and decoration.

In addition to crystal vases, Baccarat – and especially its decorator Jean-Francois Robert – pioneered a method of decorating opaque glass vases with enamel colourings. The resulting works, titled ‘opaline’ glass, reached their peak of popularity during the 1860s.

These milky, ‘opaline’ glass vases often featured hand-painted floral decorations and closely resembled fine porcelain. They were hugely popular among Victorian collectors.

Baccarat lighting: crystal candelabra and chandeliers

Three drawings from the Baccarat archives, Paris. Left: illustration of a gilt bronze mounting for a monumental crystal fountain, produced for the 1867 Exposition in Paris. Centre: The 'Tsar's Candelabrum', illustration of the monumental candelabra produced for Nicholas II of Russia in the 1890s. Right: The 'Tsarina's Candelabrum', another monumental candelabra produced for the Russian court in 1897.

Perhaps the most impressive and opulent glassware to have been made by Baccarat in the 19th Century, however, were the monumental lighting fixtures it produced for exhibitions and royalty across the globe.

Baccarat astonished contemporary audiences in 1855 when it exhibited its 17.5 foot (5 metres) tall candelabra at Paris’ Exposition Universelle. The candelabra stem were completed in a green-tinted crystal glass which contemporary observers titled ‘malachite crystal’.

In the same year, Baccarat also debuted a monumental 157-light chandelier, pictured at the top of this article. Known as the ‘Tuzla’, Baccarat was later commissioned to make similar designs for the Ottoman Sultans and the Shahs of Persia. A version of the chandelier today hangs in the Baccarat Museum in Paris.

Other monumental chandeliers made by the Baccarat company in the 19th Century include those produced for the Dolmbahce Palace, discussed earlier. In 1873, Baccarat received a large order from the Shah of Persia, Naser od-Din, for crystal lighting fixtures.

Lastly, Baccarat also completed, in the late 19th Century, another famous pair of monumental candelabra, this time for the Russian Imperial Court under Nicholas II.

Indeed, Nicholas placed so many orders with Baccarat in the 1890s that the company was forced to open an entirely new workshop dedicated to fulfilling them.

These candelabra, known as the ‘candelabra du Tsar’, never actually made it to Russia owing to World War I and the Russian Revolution which followed. One of the pair is now on display at the Baccarat Museum, while the other is in the Plaza Hotel in New York.

Baccarat today

Original 19th Century Baccarat pieces are today highly prized collectors’ items. Many of its most iconic designs – for exhibition and otherwise – can also be found at the firm’s museum in Paris, on the site of the ‘Chateau’, the residence of the firm’s directors.

Baccarat continues to operate as a manufacturer of luxury glassware. The company proudly proclaims that its 21st Century pieces are ‘shaped by the dialogue between heritage and modernity’.

That this 'dialogue' is able to happen - that is, the fact that many of its most famous 19th Century pieces are still in production - attests to the elegant, timeless quality of the originals.