When it comes to sculpture, we unfairly think of bronze as marble’s older, less glamorous sister. Bronze is more commonly associated with public monuments than with ‘fine art’, while marble is the medium of the Venus de Milo, of the Ecstasy of St Theresa, and of David.

Of course, this hasn’t always been so. Bronze has, for millennia, represented an ideal medium for sculpture, favoured by artists because of its versatility, its rich colouring and its ability to achieve the finest of detail.

Some of the first known sculptures were completed in bronze. Many artists – as we will see – are known more for their work in bronze than anything else.

And unlike marble, bronze encompasses the whole range of what we might consider ‘sculpture’, from small figurines, to monumental statues, to modern abstract pieces.

What is bronze sculpture?

A bronze sculpture from Ancient Egypt (left), known as 'Seated Wadjet', dating from 664 BCE - 332 BCE, shown together with modern sculptor Henry Moore's 'Family Group' (right), made in 1949

A bronze sculpture, often simply called ‘a bronze’, is a three-dimensional piece of art made by pouring molten bronze into a mould, before leaving it to solidify.

Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin, made by heating the two metals together and allowing them to cool. Nowadays a metal qualifies as bronze only if it adheres to a strict ratio of 88% copper and 12% tin.

In the past, however, the composition of bronze varied widely. The earliest ‘bronze’ products were actually made from copper and arsenic, and many ancient ‘bronzes’ have later been revealed actually to be brass, an alloy of copper and zinc.

Bronze sculpture is made via a process known as casting: pouring molten metal into a mould and leaving it to solidify.

Casting is a very different technique to the chiselling and carving associated with marble sculpture, or the modelling associated with ceramics, but is used to achieve the same effects as both.

Why did artists choose to make sculptures out of bronze?

For artists and sculptors, bronze represents an excellent medium for producing sculpture. While marble can be difficult to work with, and easy to break and damage, bronze is a hard and ductile metal.

Bronze is also preferable to other metals because, in the casting process, it is possible to achieve both detail and consistency.

As molten bronze solidifies in a mould, it expands slightly, thereby allowing for every detail of the mould to be captured. Similarly, as it cools further, it will once again contract, therefore allowing for the easy removal of the mould.

Depending on how the mould is made, this last property of bronze can mean that some moulds can be reused – so bronze sculptures, unlike stone ones, can easily be reproduced.

Lastly, bronze is esteemed by artists because of its rich colouring. Over time, bronze develops a distinctive patina, or burnish, which gives many bronze pieces the intensity for which they are so often lauded.

And as well as being patinated, bronze sculpture can also easily be silvered (producing silvered bronze) and gilded (producing gilt bronze, or ormolu), giving it an extraordinary variety of uses, from furniture to clock-making to jewellery and much more.

How is bronze sculpture made?

Bronze sculpture can be cast using a number of different techniques.

All of these techniques, however, utilise the basic principle of applying molten bronze into a mould and leaving it to set, before removing the mould, chasing the finished piece (refining and defining the object using a hammer) and applying a patina.

Exactly how the moulds are made, and exactly how the liquid bronze is applied to the mould, is where the technical variation occurs.

In Europe, for centuries bronze moulds were produced in workshops known as foundries: a founder is someone who makes a mould for bronze-casting.

The foundries utilised a set of established techniques for making bronze sculptures, and these included sand-casting, ‘lost-wax’ casting, and centrifugal casting. Most of these methods were methods utilised in antiquity.

By far the most common technique for producing bronze sculpture, however, is the ‘lost-wax’ method.

Lost-wax bronze casting

Lost-wax casting is perhaps the oldest and most primitive form of casting, and yet is still the most widely-used today. It’s also sometimes referred to as ‘investment casting’, or by its French name, cire perdue.

It is universally favoured by bronziers because of the fineness of detail which can be achieved through the use of wax and moulds.

The entire process of lost-wax bronze casting, from start to finish, is detailed in a video produced by the Victoria & Albert Museum. This method (sometimes known as ‘hollow lost-wax casting by the indirect method’) is the most commonly-used form of lost-wax casting, but there are some variations.

The most primitive and crude lost wax technique is known as solid lost-wax casting; simply achieved by making a model in wax, creating a mould around it, melting out the wax and pouring in the bronze.

Because of the way that bronze sets, it is extremely difficult to make large pieces using this form of the technique. More commonly, then, larger bronze pieces will be made using the method known as ‘hollow lost-wax casting’, which involves more steps, demonstrated in the video.

Hollow lost-wax casting by the direct method differs from the steps in the video in that the original model is made of clay, which is then coated in wax and placed into a mould. This means that the original clay model is lost in the casting process: it becomes part of the finished piece.

Indirect hollow lost-wax casting, by contrast, preserves the original model: the sculpture can therefore be reproduced.

Hollow lost-wax-cast bronze sculptures can be made either as one whole piece, or in parts which are then welded together.

For large bronze sculptures, the artist will almost certainly make the piece in separate parts which he or she will then weld together. Often, sculptors will make a large sculpture by first creating smaller figurines, which are progressively scaled up until the sculpture can become life-size or bigger.

Painted and patinated bronze sculpture

After the casting process is complete, the sculptor must finish and decorate the sculpture. The surface will be chased in order to achieve smoothness, and any imperfections or air bubbles will be filed down.

The bronze will then be patinated, or applied with a varnish (or combination of acid and wax) which will give the sculpture its rich hue. Some finished bronze pieces can have a green or yellowish tint, and sometimes they will even appear slightly gold in colour.

Patination helps the sculptor to direct the colour of the bronze to the tone he or she desires. Often the artist will apply patina to specific details or elements of the piece, thereby emphasising the fine details and giving the piece a sense of texture and depth.

Instead of being patinated, bronze sculptures are also sometimes gilded or silvered. This was especially popular in 17th and 18th Century France, and can be achieved using a range of different techniques. For more about the gilding process, read our blog on ormolu.

Bronze objects can often be applied with other materials as decoration, such as enamels, hardstones and other metals.

One particularly impressive means of decorating bronze is the art of cold-painting, which was developed by a group of artists working in Vienna at the end of the 19th Century, chief among them famed bronze founder Franz Xaver Bergmann (Austrian, 1861-1936).

A cold-painted bronze is a bronze sculpture which has had several layers of lead-based ‘dust’ paint applied to it. Cold-painting therefore differs from enamelling in that coloured enamel has to be fired before it can set on the surface of the bronze.

History of bronze sculpture

Humans first discovered uses for bronze around 5,000 years ago, ushering in the era we now call the Bronze Age.

Bronze in these early days was used for tools and weapons, but it was not long before humans also started using it for art.

Indeed, the use of bronze for both tools and sculpture in prehistory is a good illustration of just how closely related technology and art are.

As soon as humans began to make things which were useful – like tools and weapons – they began also to make things which were beautiful, like sculpted objects.

This close relation between technology and art would continue to shape bronze sculpture for the next 5,000 years: as bronze-making technologies became more sophisticated, so too did bronze sculpture.

Prehistoric and Ancient bronze sculpture

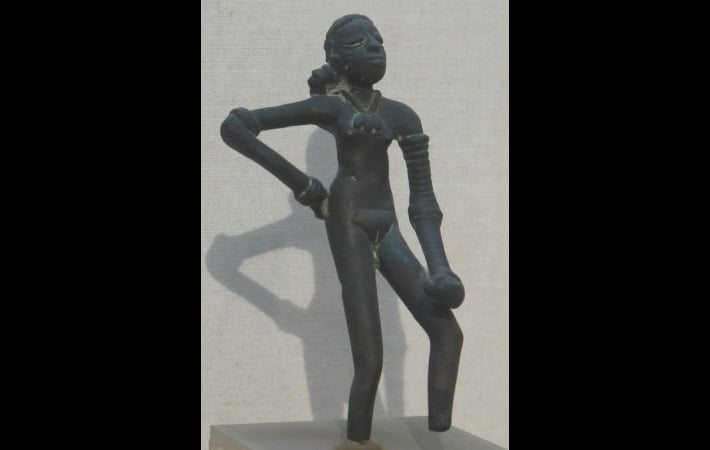

The 'Dancing Girl' of Mohenjo-daro, now held by the National Museum of New Delhi, India. © Jen via Wikimedia Commons

The Bronze Age is defined as the period from roughly 3000 BCE to around 1000 BCE, though this varies depending on the region of the world.

One of the very first known Bronze Age sculptures is known as Dancing Girl (pictured above), and was discovered on the site of the ancient city of Mohenjo-daro in the Indus Valley, modern-day Pakistan, and dates from around 2500 BCE.

What’s perhaps most astonishing about the sculpture is how well it has survived: though we know that many other civilizations of the same era – including in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China – were producing bronzes in large quantities, very few survive until the present day.

This is because bronze has a ‘resale value’: bronze figures can be melted down to make other objects, and so many large bronze sculptures from the past have been lost to scrap.

Stone, bone and ivory carvings and ceramics have, on the other hand, survived disproportionately well, because they cannot be so easily recycled.

Classical Greek and Roman bronze sculpture

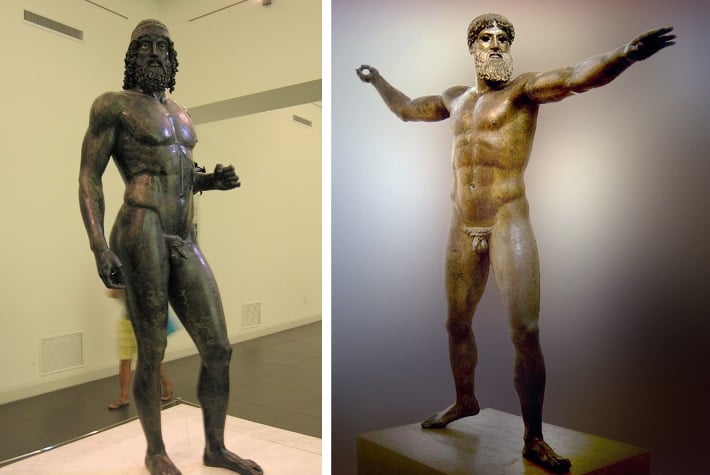

One of the Riace bronzes (left), together with the Artemision bronze (right), both 5th Century BCE. © Luca Galli and Ricardo André Frantz via Wikimedia Commons

This problem of survival was particularly true of the civilization perhaps most renowned for its sculpture: Ancient Greece.

The Greeks produced thousands of bronzes in the years between c. 700 BCE and c. 100 BCE, and these reached new levels of sophistication, but, for the reasons discussed above, very few survive.

The earliest Greek bronze sculptures came in the form of reliefs, made by hammering flat sheets of bronze over each other. These were crude affairs, particularly in relation to the civilization’s later achievements in sculpture.

The achievements of the Archaic and Classical Greeks in bronze-making were ground-breaking: for the first time in human history, artists had discovered a means of creating life-size, free-standing bronze statues. They achieved this by casting bronzes in parts and then welding the pieces together.

When the Romans took over the Greek heartlands in 146 BC, they continued the fine traditions of classical Greek sculpture, even going so far as to have plaster casts made of Greek statues in order to have them copied in bronze and marble.

Because bronze sculpture has barely survived since the Roman period, most of the evidence we have for what Archaic and Classical Greek sculpture looked like comes from these Roman marble copies.

That being said, a number of extremely rare and important Greek bronzes have been discovered in recent years, including the so-called Artemision bronze (c. 470-440 BC) and the Riace bronzes (c. 460-450 BCE), both pictured above.

These Greek bronzes give us some sense of the quality and monumentality of Ancient Greek bronze sculpture.

Medieval bronze sculpture

The Brunswick Lion, a 12th Century AD bronze figure, located in the Burgplatz in Brunswick, Germany

After the spread of Christianity across Europe during the latter stages of the Roman Empire (from the 1st Century BC until the 6th Century AD) and beyond, bronze sculpture fell into sharp decline.

This was largely a consequence of Early Christianity’s doctrinal opposition to monumental sculpture, preferring instead small ivory carvings and crucifixes.

From around 1000 AD, a period we know as the Romanesque period, there was something of a revival in sculpture. One of the most famous pieces of art from this period is known as the Brunswick Lion, dating from 1166, and is pictured above.

The Brunswick Lion is the earliest known hollow-cast bronze sculpture to have been made since antiquity – so for nearly 1000 years!

But it is precisely because of its exceptionality that the Brunswick Lion is so astonishing: even though in the Romanesque and Gothic (from c. 1200 - c. 1400) periods sculpture had been revived, these mainly took the form of ornamental stone carvings used as reliefs in churches rather than works in bronze.

One place where the tradition of bronze casting was kept alive in the Middle Ages was China, where there was a strong tradition of fine bronze sculpture.

Renaissance bronze sculpture

Panel from Lorenzo Ghiberti's gates to the Florence Baptistry, showing an allegorical relief of Adam and Eve, in gilt bronze

It was in the Renaissance, the period from roughly 1400-1600, that bronze sculpture once again returned to Europe.

The period was associated with a new interest in the art and civilizations of Classical antiquity: of Greece and Rome. Artists began to study the forms and techniques using artefacts from the Classical period, and attempted to recreate them.

As we have seen, it was because many of the surviving sculptures from Greece and Rome were marbles rather than bronzes, it was marble which became the main medium for sculpture. Michelangelo’s David is perhaps the archetypical Renaissance sculpture.

There were, however, a number of extremely important bronzes produced during the Renaissance: one of the earliest Renaissance bronze sculptures – often thought to be the piece which kickstarted the entire Renaissance movement in sculpture – was Lorenzo Ghiberti’s famous ‘Gates of Paradise’.

Ghiberti (1378-1455) completed the ‘Gates’ (actually the doors to the Florence Baptistry) after winning a competition in 1401 to design the new doors. He created 28 gilded panels, each one modelled with a Classicized Biblical scene in relief.

One of Ghiberti’s assistants, Donatello (1386-1466), also created a number of spectacular bronze figures in the early-to-mid 15th Century, including models of the Biblical figures David (c. 1425-30) and Judith (1455-60).

Mannerist bronze sculpture

Bronze figure of Mercury, after Giambologna. This figure was widely reproduced in the 18th and 19th Centuries. © Didier Descouens via Wikimedia Commons

The late 16th Century in Europe is generally considered to be a time when the High Renaissance – exemplified by artists such as Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael – was superseded by a newer, contiguous style known as Mannerism.

Mannerist sculpture in bronze was typified by Benvenuto Cellini’s (1500-1571) Perseus with the Head of Medusa, pictured at the top of this article.

Cellini’s piece was the first masterpiece to have been produced in bronze since Donatello, over half a century before. His choice of the medium was intended to be a bold statement, and to show that bronze casting could produce works that were on a par with marble works.

Cellini also believed that the act of pouring molten bronze into a cast was the act of giving a sculpture its ‘life-blood’: he was making his figure ‘come alive’.

It was also at this time that there was a growing interest in collecting among Europe’s powerful upper classes. These noble families began not only to commission monumental sculptures (like the Perseus) for grand public spaces, but smaller items for their homes.

The Flemish-born Italian sculptor Giovanni da Bologna (known more commonly as Giambologna) was particularly important in this story. He was a prolific sculptor, producing many bronze statuettes for important clients across Europe.

Baroque bronze sculpture

Giambologna's 'Kidnapping of the Sabine Women' in marble and bronze. The marble (left) is the original version in the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence, while the bronze (right) is a later copy

As the Mannerist period of the late 16th Century moved into the Baroque period of the 17th Century, the art of sculpture underwent some important transformations.

Baroque sculpture was more dynamic and dramatic than its Mannerist and Renaissance predecessors, and much of it was intended to be viewed ‘in the round’ rather than simply from the front.

Giambologna would become a master of the new style in bronze, creating pieces such as The Rape of the Sabine Women, pictured above. Here, the sculpture is intended to be viewed from all angles, and skilfully depicts a frozen moment of motion.

Giambologna's The Sabine Women was originally completed in marble, but Giambologna’s workshop would go on to made several reductions of the figure in bronze, and these would become enormously popular collectors’ items in centuries to come.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) was perhaps the most famous Baroque sculptor, and while he worked mainly in marble, several of his bronzes are widely revered, including his Corpus (1650), and his monumental canopy for the tomb of St Peter, St Peter’s Baldachin (1623-34).

Neoclassical bronze sculpture

Etienne Maurice Falconet's 'Bronze Horseman' at Senate Square in St Petersburg. © Andrew Shiva via Wikimedia Commons

The Baroque style in sculpture – and the late Renaissance passion for collecting – continued well in to the 18th Century.

As Baroque was replaced by Rococo, and Rococo replaced by Neoclassicism across the 18th Century, the uses of bronze in sculpture was limited to smaller decorative pieces.

Rococo sculpture found much of its expression in the new medium of porcelain: the leading makers of these sculptures were the influential factories at Sevres in France and Meissen in Germany.

Marble, on the other hand, was the preferred medium of the best known Neoclassicists of the later 18th Century, Antonio Canova (1757-1822) and Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844).

Where bronze was used for great works of sculpture, it was for dramatic commemorations of rulers, military heroes and famous national historical figures. Indeed, the association many of us make between bronze sculpture and public monuments was born in this late 18th Century period.

One of the most famous examples of such a monument is French sculptor Etienne-Maurice Falconet’s (1716-1791) monumental equestrian statue of Peter the Great of Russia for Senate Square, St Petersburg, known as Bronze Horseman.

As well as large-scale commemorative pieces, the Neoclassical age also saw a flowering of smaller bronze sculptures being incorporated into other decorative pieces, notably clocks and furniture.

The Empire style figural mantel clock is, for example, one of the iconic decorative items of the early 19th Century. Normally modelled as a Classical-style bronze figure atop a plinth, with the clock dial positioned centrally, these fine clocks stand as testament to the new versatility of the medium.

Bronze sculpture in the 19th Century

Italian-born sculptor Carlo Marochetti's bronze monument to Richard the Lionheart, outside the Houses of Parliament in London

The tradition of monumental and commemorative bronze sculpture in the Neoclassical style was continued by artists such as James Pradier (French, 1790-1852) and Carlo Marochetti (1805-1867).

Likewise, the use of small bronze figures as decorative pieces and as ornamentation for clocks and furniture also continued. The demand for these kinds of pieces were growing, as industrialisation was enriching ever greater numbers of people in European society.

This upsurge in demand would secure the success of the great Parisian bronze foundries of the 19th Century: among them Maisons Beurdeley, Barbedienne, Moreau, Picard and Susse Freres.

Many of the bronze sculptures produced in these foundries were replicas of older bronze and marble sculptures, by masters such as Giambologna and Clodion. By making astonishingly accurate casts of these masterpieces, the foundries tapped into a vast luxury market.

One particularly popularly-collected bronze figurine in the 19th Century was the Marly Horses, originally completed in marble by Guillaume Coustou (1677-1746) for the Chateau de Marly, and considered a masterpiece of French Baroque sculpture.

In the later 19th Century, new sculptors rose to fame for their pieces made solely for the domestic market: these included Jules Moigniez (French, 1835-1894), known for his animalier sculptures, and Franz Xaver Bergmann (Austrian, 1861-1936), renowned for his Orientalist bronzes and cold-painted works.

Modern bronze sculpture

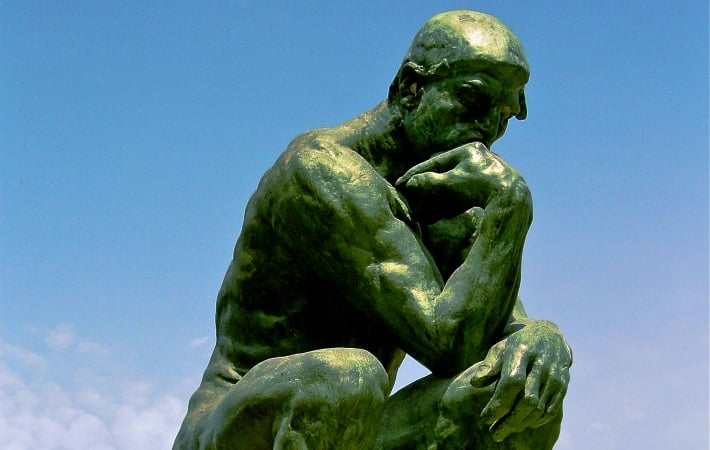

Top half of Auguste Rodin's iconic monumental bronze 'The Thinker'

Modern sculpture is often said to have begun with Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), which is all the more notable when we consider that he worked primarily in bronze.

It was perhaps Rodin’s influence which would inspire successive generations of modern sculptors to experiment with bronze, and use it for their sculptures.

Some important artists working in bronze in the 20th Century included Henry Moore (1898-1986), Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966) and Jean Arp (1886-1966) – to name just three of countless sculptors using the medium at the time.

Their abstracted and Surrealist pieces were all aimed to test the very definition of sculpture. The modern era has indeed been an age in which artists attempted to topple traditional hierarchies, hierarchies of 'high' and 'low' art, and of 'fine' and 'decorative' art.

It was because of their efforts that bronze was once again restored to its rightful place as a pre-eminent sculptural medium.

Browse Mayfair Gallery's collection of antique bronze sculpture.