From James Bond to Ocean’s 12, The Simpsons to Scooby Doo, the work of famed jewellery house Fabergé has captivated the popular imagination since the very beginning of the modern era.

It’s difficult to say exactly why Fabergé products, and especially the eggs, are known so universally across the globe. For many, Fabergé is the foremost symbol of modern luxury: every piece an exquisite treasure, carefully crafted from the most precious materials.

But more important than this, perhaps Fabergé pieces are emblems of a lost world, of the opulent majesty of pre-revolutionary Russia. They are a symbol of Emperors and Empresses, courts and palaces, war, rebellion, and diplomacy.

In their rich symbolism and their exceptional craftsmanship, Fabergé pieces are the closest a jeweller’s work can come to being fine art.

What is Faberge?

The House of Fabergé was founded in 1842 by Gustav Faberge (1814-1893), a goldsmith from a family of French émigrés, then living in modern-day Estonia. The jewellery house would swiftly move its operations to St Petersburg, and it would remain there for three generations.

It was during the second generation of Fabergé, under the control of Gustav’s son Peter Carl, that it rose to great prominence, thanks in no small part to the patronage he received from the Russian Imperial Court in the late 19th and early 20th Century.

The company name Fabergé changed hands several times over the course of the 20th Century, when it was acquired by the Rayette cosmetics company and later Unilever. The company name is now back with the Fabergé family.

Despite its turbulent 20th Century history, Fabergé’s turn-of-the-century heyday is still what gives it its fame.

It was responsible, in this earlier period, for the production of some of the most important and exquisite pieces of jewellery and objets d’art of all time.

In the late 19th and early 20th Century, Faberge were the leading practitioners of the goldsmith’s art. Pieces from this period are now in the most important collections globally – public and private – and sell for phenomenally high prices at auction.

The pieces produced by Fabergé were so innovative that they would go on to inspire a new style in the fields of jewellery and decorative arts. Fabergé style pieces would follow many of the same rules as the originals: they would be luxuriously, opulently decorated, expertly crafted, and ingeniously designed.

Who was Peter Carl Fabergé?

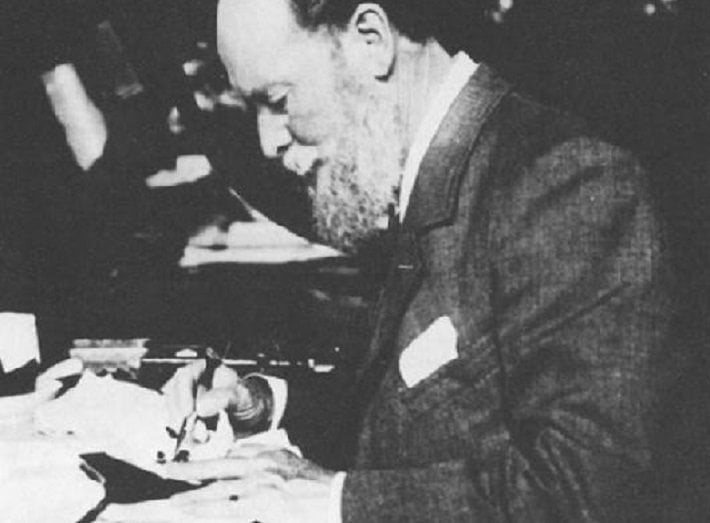

Peter Carl Faberge at work in one of his workshops

Peter Carl Fabergé, most commonly known as Carl Fabergé, Karl Fabergé, or sometimes simply Fabergé, was the man responsible for taking Fabergé to the heights it reached during the fin-de-siècle period.

It was he who made the famed Imperial Easter Eggs for Tsar Alexander III’s wife Maria, as well as introducing the other ranges of pieces which would make the company so greatly revered.

Indeed, though moderately successful, the House of Fabergé was a largely ordinary business until Peter Carl took over in 1882.

Carl joined the business in 1864, after undertaking a Grand Tour of Europe in which he learnt about – and became fascinated by – European art. He received training from a number of goldsmiths on the continent, before deciding to head back to St Petersburg to work for his father.

Those who knew him regarded him as a focused man with an acerbic wit. He insisted on studying every single piece before it went to market. He did not suffer fools gladly, as many of the craftsmen he had working for him found out to their cost!

It was this determination, and obsession with the finest, most beautiful art, that would drive Fabergé to become the greatest jeweller in the world.

When did Faberge live?

Peter Carl lived between 1846 and 1920; his working life being spent during the final years of the Russian Empire leading up to the 1917 Revolutions. During this time, the Russian court had a reputation for being extravagant and spendthrift, as well as for being Western in their outlook and culture.

Russian Tsars and noblemen had long tried to emulate what they saw as the magnificence and splendour of Europe. In their education, their fashion, their architecture and their art, the Russian elite were Europeans. Even the official language of the Russian court was French.

The Winter Palace in St Petersburg, Russia, built in the European Baroque style. © Florstein via Wikimedia Commons

Fabergé, both under Gustav and Carl, had tried to tap into this widespread Europhilia by making jewellery which resembled continental decorative arts.

Gustav, who was previously known as Gustav Faberge, even added the accent to the name ‘Fabergé’ in an attempt to make the company seem more French.

And yet, despite being born out of a desire to make Russia more European, Fabergé’s unique creations would end up achieving the opposite: convincing Europe of the beauty of Russian art.

Fabergé pieces would become totemic objects, the symbol of Russia in the world, a reminder to Europe of its ability to create beauty and luxury.

Where did Faberge operate?

Fabergé started trading in St Petersburg, but quickly found that demand for his products were growing faster than space allowed.

As the business grew, Fabergé opened workshops all over the Russian Empire and the wider world. By 1906 Fabergé had workshops in St Petersburg, Moscow, Odessa, Kiev and London.

The House of Faberge in Moscow, 1893; the building featured the Faberge showroom at the front, with the silver workshop attached.

Each workshop was supervised by a different master craftsman and specialised in different products. The Moscow branch, for example, specialised almost exclusively in silver tableware.

Each of Fabergé’s craftsmen also had their own distinctive style, and some of them – especially the masters of the St Petersburg workshop – became famous in their own right.

Erik August Kollin (1836-1901), was the first chief jeweller at Fabergé, working for Carl’s father Gustav from the very first days of the company. He was succeeded by Michael Perchin (also spelled ‘Perkhin’, 1860-1903), who became the master of the St Petersburg workshop from 1886 until his death and supervised the production of the most famous Fabergé eggs.

Perchin was then succeeded by his assistant, Henrik Wigström (1862–1923). Where Perchin's output was mainly in the Renaissance and neo-Rococo styles, Wigstrom's was closer to the Louis XVI and Empire styles.

What did Faberge make?

Of course, Fabergé is most famous for his Imperial eggs, on which more later, but these represented only a tiny proportion of the output of the great jewellery house.

Snuff boxes, picture frames, table clocks, walking sticks, jewellery, silverware, even miniature items of furniture and doorbell cases – any precious objet d’art you can think of, Fabergé probably made it.

Fabergé designed pieces in order to find the most artistic and innovative ways of displaying precious stones and materials.

For Fabergé, it did not matter whether the object was a traditionally ‘precious’ item like a pendant, or a ‘novelty’ item like an automaton doorbell: what mattered in the end was its intricacy, its originality, and its quality.

Fabergé took inspiration from the history of European arts as well as from traditional Russian crafts to make his pieces. His work displays an extraordinary breadth, both in the objects he created and in the techniques used to make them.

So whilst the Imperial eggs are by far the most famous of all of Fabergé's works, the whole range of other Fabergé pieces often display his extraordinary skills just as aptly.

Likewise, many of the best Fabergé style pieces replicate not just the eggs, but also the other pieces made by Fabergé. A few of the most common and famous ranges of Fabergé and Fabergé style objects are outlined below.

Faberge flowers

'Lily of the Valley', made from gold, enamel, diamonds, and jade, in an onyx vase, held at the Virginia Museum of Fine Art. © Chuck Redden via Wikimedia Commons

Fabergé started making its range of hardstone flower models from the 1880s. As with most Fabergé products, they drew inspiration from a range of sources to make something innovative, original, and splendid.

These flower studies combined a number of different artistic traditions. There was, for example, a widespread fascination among the 19th Century Russian elite in botany.

Flowers from France used to be transported by train to Russia on ice, purely so that Russian aristocrats could decorate their palaces. Fabergé flowers were clearly designed to appeal to this market for French flowers.

Additionally, the use of finely-cut stones, often precious gems such as agate, quartz, malachite and lapis lazuli, to make up the flower petals was a clear nod to the long tradition of Russian lapidary craft in the 18th and 19th Centuries.

One amazing feature of many Fabergé flower models was the rock crystal ‘vase’ in which the gold stem was mounted, which used a deliberate trompe l’oeil effect to give the appearance of real water.

Faberge animals

Hippopotamus carving by Faberge in nephrite jade, with diamond eyes, c. 1900, housed at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. Stone animal carvings were often rotund, quasi-comical figures.

As well as flower studies, Fabergé created a wide range of hardstone animal models, again carved from semi-precious stones like rosequartz, agate, amethyst and peridot.

Elephants and pigs were the most common animals made by Fabergé – their ‘eyes’ were normally made from precious stones and metals like diamonds and rubies.

Many of the animal models were created for important clients, including the British Royal Family, for whom Fabergé made custom miniatures of their pets! Queen Alexandra, wife of King Edward VII (reigned 1901-1910), was known for being particularly fond of these animals.

These models were occasionally combined with automaton technology so that parts of the animals moved, although these were much rarer.

The Faberge eggs

Faberge's 'Renaissance' Imperial egg, completed 1894 for the Imperial Family. © Михаил Овчинников via Wikimedia Commons

The Fabergé eggs are, however, the most impressive and revered objects produced by the company. It was the eggs which propelled the company to its legendary status.

Clearly they look impressive from first sight, but exactly how they came to be regarded as the pinnacle of the jeweller’s art requires a longer explanation.

Why where the Faberge Eggs made?

Partly what makes the eggs so valuable is the fact that they were commissioned and owned directly by the Imperial family, who ruled over Russia.

Rather than simply being another piece of art in the family’s vast collection, the eggs had a personal quality, and were given as gifts by members of the family to each other.

Peter Carl Fabergé first had contact with the Russian Imperial family through his father’s goldsmithing company, which had been employed to restore some of the pieces in the Hermitage Museum’s collection.

This work gave the young Carl a unique opportunity to study the pieces on display, and at an exhibition in the early 1880s, Fabergé exhibited a replica of a 4th Century BC gold bangle which he had been restoring.

The Tsar, Alexander III (1881-1894) was said to have announced, upon seeing Fabergé’s piece, that he could not distinguish the replica from the original.

It was the start of a long relationship between Carl and the court, and would lead, in 1885, to Fabergé’s appointment as ‘Goldsmith by special appointment to the Imperial Crown’.

The same year, Alexander III first commissioned Fabergé to make an Easter present for his wife, Maria Feodorovna. The gold, enamel and diamond egg which Fabergé eventually produced was such a success that the Tsar swiftly commissioned Fabergé to make a new Easter egg every year.

In the years that followed, Fabergé was given increasingly more artistic freedom to create the piece as he desired. There was, however, only one condition: every piece should contain a surprise.

Faberge's first Imperial Egg, the 'Hen Egg', was completed in 1885, and features the gold yolk, the 'hen' and a white enamelled exterior. Notice how this first Egg is simpler in design to many of the later Eggs. © Михаил Овчинников via Wikimedia Commons

What were the Faberge eggs made of?

These eggs were elaborate affairs, and varied significantly in design over the years. There were, however, a number of similarities between them which made them recognisably ‘Fabergé’.

All of Fabergé’s eggs were made with a naturalistic ‘shell’ made from enamel on a thin gold backing. The crisp, delicate enamelling gave the eggs a particularly authentic feel, like the shell of a real hen’s egg. The eggs then normally opened to reveal a gold ‘yolk’ which contained the surprise.

Materials used in Fabergé eggs normally included gold, silver, platinum, diamonds, enamel, and rubies. All of the most luxurious, expensive and extravagant materials made their way into the Fabergé eggs.

And because these were presents for the Tsar’s family, many of the eggs also featured Imperial insignia and portraits of the Romanov family, painted on ivory in miniature.

Perhaps the most iconic egg was the Coronation Egg (shown below), produced in 1897 for the coronation of Tsar Nicholas II’s wife Alexandra Feodorovna as the Empress of Russia.

Faberge's Imperial Coronation Egg, completed in 1897. © Miguel Hermoso Cuesta via Wikimedia Commons

It has an outer shell made from gold, enamelled in yellow using the guilloché technique. The ‘surprise’ on the inside of the egg takes the form of a miniature enamelled gold replica of the Tsarina's coronation carriage, which formerly contained an emerald stone.

How many Faberge eggs were made?

Fabergé made 69 Easter Eggs in total, of which 50 were the ‘Imperial Eggs’ made for the Tsar’s family.

This included one egg per year made for the Empress Maria, wife of Alexander III, and two eggs per year for the wife (Alexandra) and mother (Maria) of Tsar Nicholas II. They were made every year between 1885 and 1917, except 1904 and 1905 during the Russo-Japanese War.

The remaining eggs were made for exceptionally wealthy clients, including several for the industrialist Alexander Ferdinandovich Kelch, the Duchess of Malborough, and Baron Edouard de Rothschild.

Of the total 69 eggs, 57 have survived; and of the 50 Imperial Eggs, 43 have survived.

The mystery attached to the missing or ‘lost’ eggs is partly what makes them such an intriguing subject for popular culture, not least since their ‘discovery’ is always the subject of huge media fascination.

The discovery, for example, of the Third Imperial Egg of 1887 at a flea market in America caused a huge sensation.

Faberge's third Imperial Egg, completed in 1887, was recently discovered at a flea market in America. © Wartski via Wikimedia Commons

Where are the Faberge eggs now?

Many of the eggs are held in private collections around the world. The Russian businessman Viktor Vekselberg is known to have the world’s largest private collection of Fabergé, including ten of the original Imperial Eggs. Most of these were bought from the American Forbes family.

The British Royal Collection also has a large number of Fabergé eggs as well as other Fabergé pieces, and there are large public collections of Fabergé on display at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in the USA, the Faberge Museum in St Petersburg and the Kremlin Armoury in Moscow.

What are the Faberge eggs worth now?

As they are mostly part of large collections, Fabergé eggs are extremely rarely traded as part of publicised sales.

One relatively recent sale of a Fabergé piece was the Rothschild Egg, produced for Germaine Alice Halphen for her engagement to Baron Edouard de Rothschild in 1905.

The egg sold in Christie’s in 2007 for nearly £9 million, making it the most expensive piece of Fabergé ever to have sold at auction.

Why is Faberge so famous?

All Fabergé pieces – the eggs, the flowers, the animals and the rest – have come to be viewed as amongst the most exquisite objets d’art produced anywhere in the world at the time, and possibly of all time.

There is a certain amount of intrigue and glamour attached to the fact that many of Fabergé’s pieces were produced for the most important and wealthy clients in the world at the time, certainly, but there are many other reasons why his pieces, and pieces made in in the Fabergé style, have come to be seen as so exquisite.

To start, Fabergé’s jewellery is deeply original and individual. Pieces were not mass produced and did not fit a certain formula. He produced an enormous range of different pieces, to suit different tastes and styles. Only a few of his pieces were made to be worn – the majority were made to be kept, displayed and treasured.

As Fabergé famously said in an interview of 1914, ‘Tiffany, Cartier, and Boucheron are people of commerce. I am the artist jeweller. You can spend millions of rubles and buy strings of pearls – but if you want something artistic, you have to come to me.’

But as well as their artistic qualities, Fabergé pieces are revered for their technical qualities.

Fabergé pioneered the use of several innovative and painstaking production processes, thanks in no small part to his obsessive perfectionism. He would make 10 or more wax models per item, starting completely from scratch if he was not pleased, and would insist on inspecting every single product before it was sold.

This included reviving the so-called ‘lost art’ of enamelling. Many craftsmen in Europe were making use of the technique in the 19th Century, but very few outside of Japan were applying it to fine pieces of jewellery.

Detail from one of Faberge's eggs completed for a private client, known as the 'Kelch Rocaille Egg'. Notice the particularly fine, elaborate finish on the green guilloche enamel. © Hank Gillette via Wikimedia Commons

He perfected the guilloché technique as well as the en ronde bosse enamelling technique, and invented a new method of application which involved adding layers of differently-coloured enamel to a piece, giving the object a sense of texture and lustre.

In addition to his technical and artistic accomplishments, Fabergé became famous because he made a lot. Across the five workshops, the output of the company was huge.

Fabergé made pieces suited for a range of people, including the very wealthy but also for the expanding Russian middle classes. Indeed, the tableware produced by his Moscow silver workshop was so popular among the Russian middle classes that they talked about ‘setting the Fabergé’ rather than ‘laying the table’.

No matter who was buying the pieces, Fabergé objects were regarded as objects of desire, of luxury, and of artistic beauty.

How can I recognise a Faberge piece?

The most important thing to look out for when determining whether a piece is Fabergé or not is the quality.

Fabergé pieces, and the best Fabergé style pieces, should be made from precious materials, and they should display a superior quality of metal casting, enamelling, and jewel setting.

Real gold and silver should, for example, be hallmarked; and the quality of enamelling can be tested by looking for unevenness, ‘bubbles’ under the surface, and consistent colouring.

Faberge’s marks

Fabergé did, of course, have his own mark, which most commonly looked like the following:

A Faberge mark. The mark also often appeared with the twin headed Imperial Eagle above it

There were, however, different marks for different workshops: St Petersburg pieces, for example, are marked ‘Fabergé’ in Cyrillic script, while Moscow pieces are marked ‘K. Fabergé’ in Cyrillic, and London pieces are marked ‘Fabergé’ in Latin script.

Because the marks were easy to copy, the existence of a mark does not equate to authenticity and is not always the best guide to the value of a piece. Collectors and buyers should look for quality above all else.

What is Faberge style?

‘Fabergé style’ pieces are pieces made outside of his workshops, but which use the same models, subject matters and stylings as Fabergé pieces. These vary quite significantly in quality, but the best utilise only the finest materials and aspire to the same levels of craftsmanship as employed by ‘real’ Fabergé pieces.

Fabergé style pieces are the same kinds of objects that Fabergé himself made, including animal sculptures, hardstone flower models and, of course, the eggs.

Indeed, the very best objects produced in the ‘Fabergé style’ are fine works of art in their own right and allow collectors to own magnifcent treasures of supreme quality, but without the huge price tag attached original Fabergé works.

Faberge in the modern era

The Fabergé company lived on into the 20th Century (even if it was not strictly a jewellery company!) but it was never able to surpass the heyday of its time under the leadership of Peter Carl.

It was for this period in its history that Fabergé will be remembered as the foremost jewellery company in the world.

The Fabergé eggs have become deeply ingrained in popular culture throughout the 20th Century, appearing in a vast array of popular books, films, and TV shows.

And in art, too, Fabergé continues to inspire: contemporary US artist Jonathan Monaghan recently created a famous series of prints titled ‘After Fabergé’, in which he updated the eggs for the digital era, giving them modern, everyday features like solar panels, mini Starbucks cafes, and USB charging ports.

In doing so, he aimed to ‘transform an iconic symbol of status and wealth into uncanny objects composed of modern furniture [and] computer parts’, thereby attesting to the synonymity of the name Fabergé with luxury, wealth, and craftsmanship.

What greater compliment to the work of the great jeweller?