The late 19th century and early 20th was one of the most peaceful, prosperous, and influential periods in all European history. Considered a golden age in the history of the continent, it was both internationally the time when European nations and European civilisation exerted their greatest sway on the world, and domestically when France and other great nations flourished and prospered like never before: all the while maintaining a deep connection to their past.

The world of decorative arts and antiques offers the optimal lens with which to enjoy this period, and in particular, the work of Czech-born cabinetmaker François Linke, who is widely regarded as one of the finest ébénistes, makers, and craftsmen, not just of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, but of all time, certainly within the realm of French decorative arts and antiques.

His work, combining traditional and modern styles and methods, stands apart from his contemporaries, possessing an originality that the work of few other master craftsmen achieve. In this article we would like to share with you what it is that makes Linke’s work so good, why he commands such respect, and how he encapsulated the spirit of the French Belle Époque.

The French Belle Époque & Belle Époque Antiques

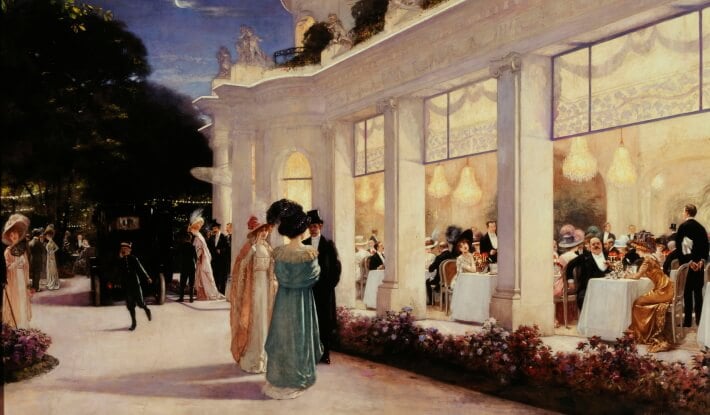

Une soirée au Pré-Catelan (An evening at Pré Catelan) by Henri Gervex, 1909. Less well-known now than Pissarro, Renoir, or Monet, Gervex and his paintings nevertheless give us unparalleled snapshot into the Belle Époque, and he depicted, better than anyone, the atmosphere, style, and modernity of Paris in this era.

While the term ‘Belle Époque’ could be applied to much of Western Europe and the wider English-speaking world, it generally refers to France from c.1870 to 1914, as we have explored in our blog: The Belle Epoque: Guide to the Age of Beauty. France was not so much the political centre of this period, as it was the cultural centre, known for its beauty, art and fashion, and the Parisian lifestyle.

Belle Époque is an anachronistic term: applied after the First World War to describe a Europe untainted by such horrific conflict. The dates for the period are usually taken as the end of the Franco-Russian War in 1871, and the beginning of trench warfare in Europe in 1914. But the period is important for more than the obvious and important fact that Europe was at peace, it was a time of immense cultural development and in many ways, it formed the origins of modernity.

This is the context and the time in which we find stepping forward a wave of bold, innovative, artists and craftsmen, working across all fields of cultural life and production. Artists and artisans began to break away from older methods and traditions, and instead look to the future, with a newfound optimism and ambition.

Antiques demonstrate this shift perfectly, most evident in the work of Francois Linke, France’s finest, and possibly last, great ebeniste.

A Linke commode formerly in Mayfair Gallery’s collection, with a beautiful parquetry scene on the front. The exquisitely conjured landscape crafted purely from inlay in various wooden tones demonstrates the quality of Linke’s work: rarely before had such three-dimensionality and atmosphere been conjured with this technique.

Francois Linke: His beginnings in the early Belle Époque

Born in June 1855, Linke grew up in the small town of Deutsch Pankraz, now known as Jítrava, in the Czech Republic. Closer to Dresden than to Prague, he found himself drawn westwards, travelling from Prague and Budapest to Germany, Weimar, and finally to Paris, where he settled in his early to mid-twenties.

In the brief autobiography he gives of his own life, Linke mentions only that he had a very hard apprenticeship with a ‘Monsieur Neumann’ in Reichenberg and worked in an unknown studio in Weimar before moving, disappointed with Germany, to Paris - perhaps the only suitable location for his budding ambition – where he was married and self-established at age 26.

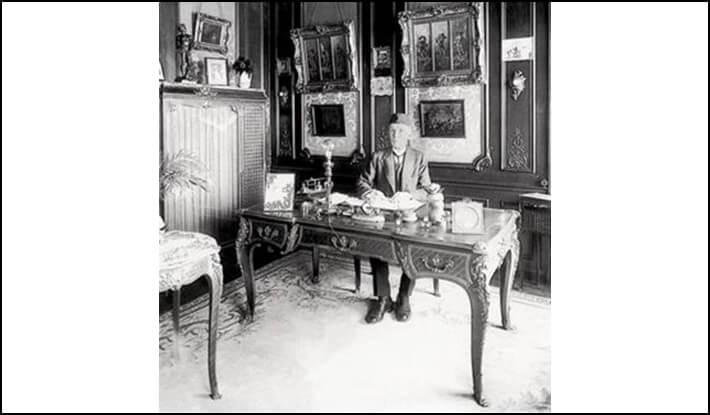

Francois Linke in his study c.1930, taken by an unnamed photographer. One would hardly suspect, judging from his modest appearance, that he would have had such an enormous impact on French art and design, or enjoyed such a prolific and successful career.

In the early years of the Belle Époque the style was defined by reproductions and copies of France’s former Royal periods and styles, as this fine piece, a direct copy of the famous Louis XV Bureau du Roi, now in the Wallace Collection, demonstrates.

Carl Dreschler, a copy of Louis XV’s Bureau du Roi, made after the alterations of 1794, when the original interlaced Ls of Louis XV were replaced with biscuit porcelain Sèvres plaques and elements of the marquetry decoration were changed.

Though exceptionally well crafted, it has a somewhat derivative quality: the craftsmen involved were clearly focused above all on reproduction. From a historical perspective this made sense: France had been through a seriously tumultuous period, thrown from crisis to crisis. It makes sense that in terms of decorative arts people were focused on stability and continuity: reasserting earlier styles rather than creating new ones, in order to give the wealthy of Paris a sense of security.

Linke did make versions of this piece in his career, and probably learnt from a young age by being involved in the production of ‘copy’ pieces such as this, but there is strong evidence of a creative streak from an early age, and by the time he made works in this model under his own name, they bear significantly more flair and freedom.

The urge to reproduce earlier works remained an undeniable force in the French psyche, and even Linke did not break from it. Works in the manner of Adam Weisweiler (1744-1820) and Jean-Henri Riesener (17834-1806), such as the piece below from the earlier years of Linke’s workshop, remained staples of his oeuvre throughout his life – the earlier pieces closer to the originals, the latter works closer to Linke’s own style.

Linke roll-top desk in the style of Jean-Henri Riesener. The piece, with its trellis decoration, vernis martin panels, and clear, square tapered lines and structure is very Neoclassical in style, with little of the Rococo flamboyance and ormolu grandeur that defines his mature output.

Collaboration with Leon Messagé and the Paris Exhibition of 1900: Linke’s Transitional Style

As his career progressed, Linke collaborated with the sculptor Leon Messagé. Though superbly skilled in woodwork, Linke required an artist’s eye to elevate the bronzes and mounts that adorned his pieces if he was truly to make his mark. By doing so, Linke succeeded in not just reproducing Louis XV pieces known in public collections; but in developing a new, transitional style, in line with changing tastes.

The continuing economic success of his workshop – and that of other makers – depended on the constant innovation of their craft. The prosperity of the Belle Époque helped guarantee a market for furniture houses such as Dasson and Beurdeley to some extent, but the French love of the Rococo style only extended so far. A way to adapt earlier styles and bring the old Romantic love of fantaisie through the waning years of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth was crucial.

For this he looked to Messagé, who had previously helped the maker most closely associated to Linke, Zwiener, win the Gold Medal at the 1889 Exposition Universelle. Together their shared expertise proved formidable, and the exquisite artistry of Messagé’s metalwork gave Linke’s work a grandeur, exuberance, and beauty that embodied the French Rococo with a newfound openness and creativity – unstifled and free.

A detail from a Linke side cabinet, that forms part of the Mayfair Gallery collection – the caryatid-like busts on the corners of many of Linke’s pieces, such as the one shown, are indebted to Messagé, and they imbue Linke’s work with a sensual, gracious femininity and sculptural appeal.

The telling moment, and most important single event of Linke’s career, was the Exposition Universelle of Paris in 1900. Having established himself as an independent maker and able to command his own workshop, he took the bold step of effectively staking his whole life and career on this event in an act of daring entrepreneurship.

The grand arch of the Paris Exposition of 1900. The French have always had a love of exposition and artistic display, and this exhibition at the turn of the 20th century was one of the most spectacular in history, with representatives from all arts and crafts present.

At this event, he made a series of highly costly works without any promise of success or of prospective buyers. Linke took advantage of the global stage offered by the event in order to put his pieces in front of an international clientele, and his gamble paid off.

What is perhaps most telling about Linke’s success at this exhibition is the degree of popularity and renown he enjoyed, at an event that simultaneously marked the high point of the Art Nouveau.

As such, it demonstrated his forward thinking and fashionability: here was a furniture and cabinet maker who was able to adapt the historical styles of royal eighteenth century France and make them into something modern and desirable.

An important Louis XV style bombe vitrine by Linke, c.1900, seen at the 1900 Exposition; the mounts by Leon Message (image courtesy of Sotheby's). This fine piece is an excellent example of Linke’s transitional style, improving upon earlier models, but not yet developed into something new and unique.

Linke’s grand style into the Twentieth Century

Linke developed his mature style in the years after the Paris Exposition by adopting many of the principles of the philosophical basis behind the Art Nouveau, in particular its insistence on function defining form and the idea nature should always be the ultimate source of inspiration.

The stylistic influence of the Art Nouveau is evident most clearly in the sinuous arcs, curves, and fluidity of form that characterises much of Linke’s mature output. Take, for example, his grande bibliotheque, or his bombe shaped vitrines. Compared to earlier works, for example Louis XVI Neoclassical or Napoleon III furniture, his works have an indulgence, grace, and grandeur to them that is more than just a revival of Louis XV Rococo or Baroque.

Left: Interior from the Horta Museum, Belgium – a beautifully preserved house to the Art Nouveau, demonstrating the elegance, grandeur, and luxuriousness of a movement inspired by nature, alongside a parquetry detail from Linke’s Grande Armoire (shown right), showing the Art Nouveau influence on his work.

His pieces are almost living libraries: pieces carved beautifully and hewn from wood, still embodying that living, breathing natural presence, and subsequently extravagantly embellished with gilding and bronze mounts. The curves and bombe-form of his pieces appeal to a natural foundation, and as such they have an honesty, beauty, and grace that makes them more than just a reinterpretation of earlier traditions. They form a connection between France’s traditional styles of the past, and the innovation and modernity of the Art Nouveau and hope for the future.

A wonderful example of this is his Grande Armoire, a watercolour of which, imagined in situ, is shown at the top of this feature. The wonderful natural quality of the work elevates Louis XV Rococo to a new level, springing with grace both from the wood from which it is made and from the wall in front of which it sits.

This evolution is evident when comparing a masterpiece: Linke’s Bahut Marine, with the Bureau de Roi and Riesener-inspired works shown above. This magnificent work, incomplete at the time of the Paris exhibition and finished in 1904 in time for the St. Louis World Fair, is so elaborate, creative, and lavishly furnished, that it makes earlier styles look tame. By the time Linke reached his mature style, a piece’s function became a mere starting point: he seemed determined to break down the divide between furniture and fine art: a piece’s beauty was the sole defining guiding principle.

Linke’s ‘Bahut Marine’: a unique piece, an ormolu-mounted kingwood, satine, mahogany and marquetry cabinet, with extensive gilding depicting water nymphs, river gods, and underwater life.

Gone too by this time are the stringent divides between decorative pieces, fine art, or larger-scale disciplines such as architecture – another tenant of the Art Nouveau. The piece has an architectural quality, and the façade appears like a portal into an otherworldly underwater realm, flowing with golden artistry and luxury. The artistic prowess of Leon Message combined with Linke’s design genius truly make this work a masterpiece from all fronts. Linke also accomplished all of this at a time when others failed to adapt. Dasson and Beurdeley, previously mentioned, and other great historical makers and furniture houses did not survive in the twentieth century, let alone thrive as did Linke.

The Legacy of Francois Linke and of the Belle Époque

The story of Linke is important because it is in ways the story of the Belle Époque itself. Within the promise of his work is also tied the promise of the era. He successfully brought traditional crafts into the 20th century, transforming and keeping alive a thriving field of decorative arts by adapting it to new tastes and changing artistic movements.

As a consequence the trauma and damage wrought by the Great War is all the greater: the tragedy of 1914 extended across all fields of life, and it created a sharp divide in history, breaking modern Europe away from its heritage to a large degree, and damaging some fields beyond repair: Linke is effectively the last great ebeniste, and in his work he embodies the culmination of one of Europe’s greatest artistic legacies.

Mayfair Gallery's collection of works by Linke

As a gallery specialising in the very finest decorative art from France in the 19th century, we often have the pleasure of showcasing works by Linke.

From his most grand creations, to works in the style of other makers and pieces that he revisited time and again during his career, Mayfair Gallery has seen it all.

Explore the works by Linke in our collection here.