It is easy to think of sculpture simply as a decorative art, but tracing the history of sculpture back to its origins reveals a much more complex story.

The history of antique sculpture reveals a fascinating story and demonstrates how sculpture has been used for reasons as diverse as political, commemorative, religious and historical.

Ritual and display: the earliest carved creations

Thousands of years ago, our prehistoric ancestors carved in rock or wood before they began to produce cave paintings. Sculpture is therefore likely to be the oldest form of visual art.

This early arrival of sculpture was partly born from necessity, as the very first carved objects took the form of practical tools to be used rather than artworks to be admired.

However, as technical abilities developed and the art of carving became more widespread, sculptures for use in rituals became commonplace.

Intriguingly, the prehistoric peoples seem at first to have simply replicated the carved tools, weapons and vessels in oversized versions, and used these as religious offerings.

Polished jadeite axe from the Neolithic period, held in the Museum of Toulouse © Didier Descouens via Wikimedia Commons

Soon, figures of men, women, and animals were created, and used in ritual settings to honour the spirits.

The shape of the figures seem to represent the desire of the devotee. For example, oddly shaped male figures seem to indicate prayers for strong sons, while overly large animals express a hope for abundant game and fish.

Such works were often crafted from precious, impractical materials, so it is plausible that these early sculptures could also have been used for display.

For example, in China, Mexico and Neolithic Europe, jade and other types of greenstone were used.

A kneeling statue, shown below, dating to the Chinese Shang dynasty (13-11th Centuries BC) demonstrates the skill and craftsmanship involved in the ancient Chinese art of jade carving.

A Chinese jade statuye from the Shang dynasty © Zcm11 via Wikimedia Commons

Fit for a Pharaoh: sculpture in the ancient Egyptian world

The first ancient culture to truly explore the potential of sculptural art was ancient Egypt.

Much of ancient Egyptian visual art was strongly rooted in their belief in life after death, and was created in accordance with this.

Bodies of rulers and nobility were buried in monumental tombs and pyramids, accompanied by all the provisions that the deceased might require in the afterlife.

Within these tombs too would be statues of life-size, or even larger, which were carved in materials such as slate, limestone or precious alabaster.

Such statues often depicted the Egyptian rulers, nobility and gods, to watch over the deceased in their tomb.

Perhaps more intriguing than these large works are the hundreds of small statuettes that survive from the Egyptian pyramids. These miniature works were made from clay or wood, and exhibit an astonishing degree of naturalism.

Each statuette depicts people engaged in everyday activities, such as cooking, sailing and farming. These small sculptures were thought to bring pleasure to the deceased in the afterlife, by portraying images of desired or enjoyed events.

Ancient Egyptian wooden model of a cattle shed from the tomb of Meketre, c.1981–1975 BC

Crucial to Egyptian sculpture was its clear presentation of more abstract ideas. Just as prehistoric offerings rendered animal body parts larger to express hope for a good hunt, so too did the Egyptian sculptors use size to convey ideas.

This is true of the depiction of Pharaohs in ancient Egyptian sculpture, who are made larger than figures of a lower social status.

A good example of this is the colossal figure of Ramses II, positioned at the entrance to his tomb at Abu-Simbel in Egypt.

The monumental sculpture of Ramses II at the entrance to his tomb in Egypt; a human figure can be seen seated in front of the statue for scale

Here, sculpture is used to convey the strength, power and command of the political leader.

Similarly, the Egyptians often combined features from various creatures to symbolize ideas. For example, the human head of the pharaoh Khafre was added to the crouching figure of a lion to form the Great Sphinx of Giza.

This suggests that the Pharoah possesses the powerful combination of human intelligence and animal strength.

It is clear that for the ancient Egyptians, sculpture was representative of more than just decorative ambition.

Rather, it could be used for political and burial purposes, to show the power of Egyptian kings and to aid the deceased in a joyous afterlife.

Sculpting perfection: Classical sculpture in ancient Greece

Despite the sculptural success of ancient Egypt, it was the ancient Greeks who became truly synonymous with the art of sculpture.

Sculpture became one of the most important forms of expression for the Greeks, with the human figure as the principal subject matter.

Beginning in the late 7th Century BC, the ancient Greeks’ sculptural abilities rapidly progressed. The 7th to the 4th Centuries BC saw a momentous shift from archaic, abstract forms to more naturalistic ones.

Figures became more realistic and detailed; these changes can be clearly seen below when comparing a standing male figure from the Archaic period with one from the Classical period of ancient Greek sculpture.

The Anavissos Kouros in the Archaic style, 6th Century BC (left) and Polykleitos' Spear Bearer in the Classical style, 5th Century BC (right) © after Polykleitos the Elder via Wikimedia Commons

The function of ancient Greek sculpture was multi-faceted. While some may have been intended for decorative purposes, much sculpture was created for political and historical reasons, to demonstrate the greatness of the ancient Greek race, or for religious reasons to honour gods and goddesses.

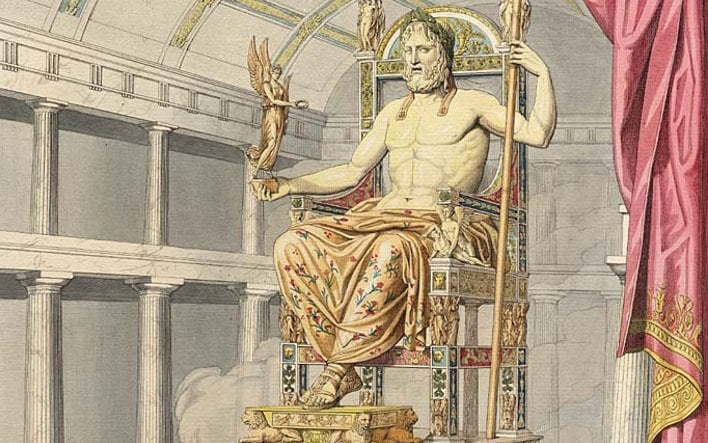

Indeed, ancient Greek sculpture is famous for its cult images, such as the colossal statue of Zeus at Olympia, which was created in the 5th Century BC by the Greek sculptor Phidias.

At over 13m high, this monumental work was carved to honour the deity, and to provide worshippers with a tangible form to direct their devotion towards.

Although the original sculpture was destroyed in the 5th Century AD, from ancient Greek descriptions and images on coins it is clear that the statue was a particularly lavish affair, embellished with gold, ivory, ebony and precious stones.

French art writer Quatremere de Quincy's impression of the statue of Zeus at Olympia, c. 1815

Back to reality: ancient Greek Hellenistic sculpture

Classical Greek art, which lasted throughout the 4th and 5th Centuries BC, was intent on depicting an idealised form of the human body, and the glory of ancient Greece.

These principles are evident in Polykleitos’ spear bearer (see above), with the figure’s muscular physique and symmetrical features.

By contrast, later Greek sculpture from the Hellenistic period chose to emphasise realism rather than perfectionism.

A new interest developed in the more extreme phases of life, such as childhood and old age, and sculptors began to depict their subjects in as detailed a way as possible, not shying away from portraying difficult and uncomfortable ideas.

A profound example of this is the below image of the Hellenistic sculpture of the drunken old woman, who sits clutching desperately at an empty wine jar, her eyes imploring pity and kindness from the viewer.

Hellenistic sculpture depicting a drunken old woman: the original on the left; a later copy on the right, showing the original placement of the woman's hands around the wine jug

Roman rule and its influence on sculpture

Although the ancient Greeks were defeated by the ancient Romans centuries later, the conquering nation were greatly impressed by the artwork of ancient Greece.

In fact, ancient Greek sculpture had been imported to Italy even before the Romans defeated the Greeks.

From the early days of the Republic, Romans imported examples of Greek art, ordered copies of famous Greek works, and commissioned Greek sculptors to carve Roman subjects.

The inventiveness of Roman sculptors added to this Greek heritage, and by building upon the work of their predecessors, Roman sculpture became more and more advanced.

Importantly, the Roman sculptors were the first to truly explore sculpture as a medium of portraiture.

The Roman use of sculptural portraiture was often for political purposes, and in an age with a largely illiterate population, sculptural busts of Roman rulers, such as the one below, became essential to signify the power of the Empire to the Roman people.

Statue of the Emperor Augustus, 1st Century AD © Till Niermann via Wikimedia Commons

This phenomenon was particularly true for the Roman colonies, where often there was an additional language barrier and visual art was all the more important. Images of the Empire and Emperor hoped to inspire devotion to Rome and its grandeur in the viewers.

The statute of the Emperor Augustus (above), for example, with its raised hand and serious gaze, conveys an image of might, strength and nobility.

Thus Roman sculptural portraiture became symbolic not only of the Emperor, but of the Roman Empire as a whole, and aimed to instil feelings of devotion in the viewer.

However, despite their exceptional talent and beautiful works, sculptors were not regarded as 'artists' but rather as craftsmen, who created works with the commission and support of patrons.

Even in ancient Greece, sculptors appear to have retained much the same social status as other artisans, and perhaps not much greater financial rewards. As a result, much of the sculptural work produced in the ancient world was unsigned.

This status contrasts greatly with the present day understanding of the creation of sculpture, which is regarded as the realm of the artist.

Early Christian sculpture

After the fall of Rome and the rise of Christianity, the production of large sculptural art began to diminish in Europe.

While the Roman tradition of portrait busts continued, the creation of monumental religious sculpture fell into decline.

This was partly due to religious doctrine, and thus sculpture that was created in the early Christian period largely consisted of smaller, more decorative works such as book coverings or diptychs.

It was not until the 11th Century that sculpture was once again embraced as a figurative art form for monumental works, when there was a general revival of the arts across Europe.

The primary style to emerge from this was the Romanesque, which combined elements of the Roman tradition with early Christianity.

The majority of Romanesque sculpture is Biblical in subject matter, with a great variety of themes depicted.

The purpose of these sculptural carvings, particularly those inside churches, was to instil the Christian doctrine in their viewers.

Scenes of the Last Judgement, for example, remind believers to recognise wrongdoing and repent, while large images of the Crucifixion convey the notion of redemption, and Christ’s love for humanity.

Visual representation of the Christian doctrine was particularly important for a society with a largely illiterate population.

Gothic Sculpture

Sculpture after the 12th century gradually changed from the clear, concentrated abstractions of Romanesque art to a more natural and lifelike appearance.

Human figures shown in natural proportions were carved in high relief on church columns and portals.

While the intention of Gothic sculpture remained similar to that of its Romanesque predecessor – that is, to make clear seminal aspects of the Christian faith – Gothic sculpture differed from earlier Christian art.

This change was largely a stylistic one, which had visual and emotive repercussions.

Gothic figures are depicted much more realistically than those made during the Romanesque period. The faces of the statues have expression, and their garments are draped in a natural way.

Detail of the Last Supper from Tilman Riemenschneider's in Bavaria, early 16th Century © Rebecca Kennison via Wikimedia Commons

The events and people depicted in these Gothic style sculptures are thus more relatable and realistic than previous forms, and resonated more profoundly with the Christian viewer.

Importantly, the Gothic era saw the rise in popularity of smaller devotional carvings, intended for personal use. These included miniature triptychs and figures such as the Virgin Mary, often carved in precious ivory.

As the Gothic craftsmen became more adept with sculpting in miniature, further intricate objects began to appear.

These included mirror cases, combs and caskets featuring elaborately carved scenes, which were used for both practical purposes and as marriage or engagement gifts.

Detail from a Gothic mirror cover, the Siege of the Castle of Love, c. 1350-70

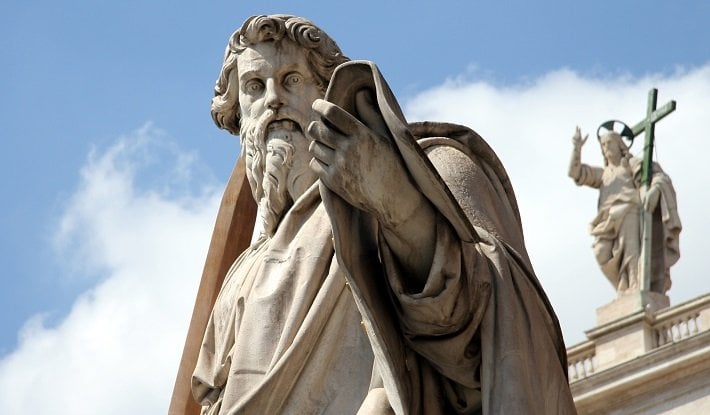

Sculpture in the Renaissance

Despite the success of Gothic sculpture in Western Europe, artistic styles were undergoing dramatic changes in Italy.

As early as the 13th Century the Italians planted the seeds of a new age: the Renaissance.

Although the elements of Romanesque and Gothic art contributed to the formation of Renaissance sculpture, Italian artists were interested in reviving the Classical approach to art, inspired by the forms of ancient Greece and Rome.

A mid-15th Century carving for example, by Renaissance artist Luca della Robbia, shows clear influence from ancient Greek and Roman sculpture.

Detail of a carving, Cantoria, by Luca della Robbia, mid-15th Century © I, Sailko via Wikimedia Commons

With its depiction of cherubs, naturalistic forms and traditional instruments, della Robbia's carving would not look out of place on a Roman sarcophagus, or as part of a Greek templar frieze.

The most significant change in art that occurred in the Renaissance was the new emphasis on glorifying the human figure.

No longer did sculpture only represent idealised saints, angels, and other religious images, but instead began to depict the human form in a more lifelike manner.

Artists began to experiment with form, style and proportion, to create sculptural works that not only stressed the glories of the Christian faith, but also the glories of humanity and mortal beings.

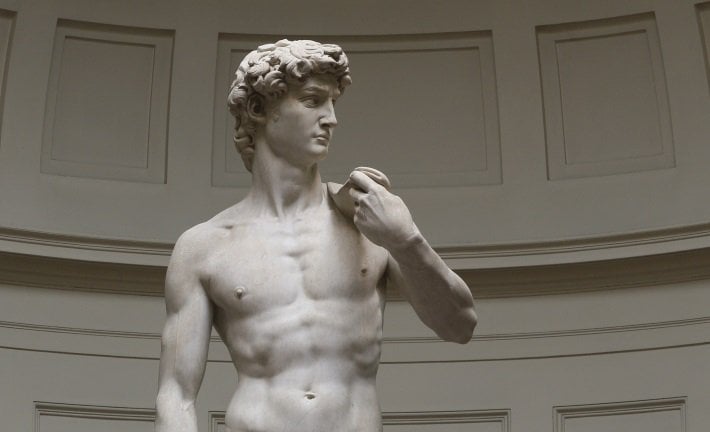

Michelangelo (1475-1564) unquestionably became the dominant figure in 16th-century painting and sculpture, and he is thought by many to be the greatest single figure in the history of art.

Perhaps the most iconic of Michelangelo’s works is the sculpture of David, created in 1504.

Slightly inclined in a gentle contrapposto pose, a trope borrowed from Classical Greek and Roman sculpture, the young Biblical hero David is depicted before his battle with Goliath.

David, by Michelangelo, early 16th Century © Jörg Bittner Unna via Wikimedia Commons

Depicting David before battle marks an important change in the artistic canon.

Instead of being portrayed as victorious after the giant’s defeat, as previous sculptors chose to depict him, David appears tense, and ready for battle.

The emphasis of Michelangelo’s David is not on the victorious and heightened glory of the fight, but rather on the human, emotional trajectory: the sculpture portrays the young hero in a state of potential vulnerability, making him relatable and altogether more human.

Depicting subjects in a more realistic, human state was of central concern to Renaissance artists, which led to an increased popularity in portrait sculpture.

Importantly, much of the Renaissance period was marked by a large increase in state patronage of sculpture intended as public art in city centres.

Similarly, as the upper classes grew in wealth and mobility, they commissioned sculptural art for their homes.

Thus, in the Renaissance, sculpture became a medium of art that could be enjoyed by individual and public alike, be it in a wealthy nobleman’s home or in a historic city centre.

Yet for the majority of the Renaissance period, even as sculptors began to experiment more freely and with more autonomy, sculpture was perceived as a relatively low craft, especially when compared to painting.

However, this perception began to change, particularly with the evident astonishing skill possessed by sculptors such as Michelangelo.

Mannerist and Baroque sculpture

As the Renaissance period came to a close, Mannerist sculptors, who attempted to build on and surpass the Renaissance style in form, finish and design, came to the fore.

What's more, these sculptors were now held in higher regard than their Renaissance predecessors had been.

This shift was not solely on account of artistic merit, but rather a changed attitude toward sculpture at the time. Indeed, artists such as Giambologna (1529-1608) became wealthy and enjoyed socialising with the upper echelons of society.

After a period of sharp argument over the relative status of sculpture and painting, sculptors producing standalone works were finally recognised on an equal level with painters (that said, much decorative sculpture on buildings remained in the remit of tradesmen).

Sculptors in the 16th and 17th Centuries continued to use the human figure as the subject of their works, but the form and style of compositions was ever changing.

Sculpture in the Baroque, for example, focussed more on the three dimensional representation of dynamic movement and energy within figural works, and portraying groups of figures assumed new importance.

Additionally, Baroque compositions were often designed to be viewed from multiple angles, and reflected a general continuation of the Renaissance move away from relief works.

As Giambologna’s Rape of the Sabine Women (below) demonstrates, Baroque sculpture was designed to be viewed 'in the round', making it ideal for display in large public spaces.

The Rape of the Sabine Women by Giambologna, 16th Century © Thermos via Wikimedia Commons

This period saw sculptors afforded greater freedom of expression and style, and hence sculpture in the Baroque flourished, with works combining the aesthetic ideals of early Renaissance works with a new and vibrant dynamism of movement.

Rococo sculpture in the 18th Century

Whilst Baroque sculpture was concerned with larger, expressive pieces, which were often designed for public viewing and admiration, there was a growing demand for smaller works.

As the emphasis on decorative interiors grew across 18th Century Europe, the wealthy nobility began to desire works that could be appreciated in their homes, which, for the most part, meant smaller figures and groups.

These smaller, more delicate sculptures were perfectly suited to the flamboyance of the Rococo style.

Primarily concerned with the portrayal of beauty and gaiety, Rococo sculpture offered a refreshing cheerfulness after the intensity of the Baroque.

The Rococo period not only introduced sculptures in new sizes, but in new materials too. Many Rococo sculptures were produced in terracotta and porcelain as well as the more traditional marble and bronze.

Porcelain figures were particularly associated with the 18th Century and the Rococo style, since it was at the beginning of this period that hard-paste porcelain was first introduced into Europe by the manufacturers at Meissen.

Meissen figures, like those shown below, were hugely fashionable during the 18th Century and continue to be popular today.

The Thrown Kiss by Johann Joachim Kaendler, Meissen porcelain Rococo style figures, c.1736 © Daderot via Wikimedia Commons

Rococo style sculpture was intended to have a pleasant, often playful, effect on interiors.

These works were designed to be admired for their skill and witticism, and thus were more ornamental and decorative than the sculptural variants that came before.

19th Century Neoclassical sculpture

Whilst Rococo sculpture retained its popularity in the late 18th Century and into the 19th Century, there was a growing desire for sculpture in the Neoclassical style.

Neoclassicism emerged as a reaction against Rococo flamboyance, but also as a result of a renewed interest across the arts, literature and architecture in Classical subject matters.

In part this new interest in Classical forms of sculpture emerged out of new archaeological excavations - most famously that of Pompeii - which had unearthed antique marbles from ancient Roman civilisations.

The Neoclassical style saw a return to Classical subject matter, yet avoided the rigidity of strict Classical form.

The two most commanding figures within the field of Neoclassical sculpture were the Italian sculptor Antonio Canova (1757-1822) and the Danish-born Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844).

Both men studied and worked in Rome, where they were famous internationally for the beautiful forms and harmonious proportions of their sculptural works.

Many of these Neoclassical works took Greek and Roman myths and legends as their subject matter, and depicted moments of heightened emotion, in this way tying in with the emerging Romantic movement.

The statue of The Graces Crowning Venus, below, is a brilliant example of a work inspired by both Canova and Thorvaldsen; the original image was produced as a sculptural relief by Canova, and made into a full-sized statue by Thorvaldsen.

This stunning work, with its delicate detailing and refined elegance, is typical of the Neoclassical style.

Marble sculpture of the Graces crowning Venus by Antonio Frilli, after Canova

From Neoclassicism to Modernism and beyond

Neoclassicism remained popular as a sculptural style into the 19th Century, a period which also saw the revival of Baroque and Rococo styles of sculpture, as well as new styles like Romanticism, and later, Art Nouveau.

This proliferation of different styles of sculpture, all existing at the same time, set the precedent for the 20th Century, a period which, with the birth of abstract and conceptual movements, tested the very definition of sculpture.

Styles and types of sculpture are now so numerous that it would be meaningless to list them in their entirety, but they nevertheless represent the great level of artistic appreciation that society today has for sculptural works.

The preservation and conservation of so many wondrous Old Master and antique sculptures allows us to celebrate these works alongside modern creations.

Whether it be a bust or a flowing relief sculpture, our fascination with creations of the bygone era, and particularly our mortal affixation with the human form, have been a constant source of inspiration for thousands of years, and will continue to do so for many years to come.

Browse Mayfair Gallery's collection of antique sculpture.