Perhaps the defining feature of Japanese history has been the country’s near ceaseless negotiation of its place in the world.

For thousands of years, the inhabitants of those islands in the northern Pacific have found themselves confronted with a stark question: what is Japan, and how should it relate to the wider world?

Should Japan be an inward-facing society, protective of its own customs and traditions? Or should it open itself up to the rest of the world, to share and be shared, but to make itself vulnerable to the vicissitudes of global geopolitics?

The Japanese Meiji period, defined as the period between 1868 and 1912, was an era in which artists were forced to respond to these questions on a new scale.

Meiji Japan was famously the era in which, after nearly 300 years of almost complete isolation from the globe, Japan began to trade openly with Europe and the West.

Consequently, Meiji Japan saw a new flourishing in the arts, as craftsmen and artists found their work in high demand overseas. It would lead to a vast expansion in production, and the development of a new 'national' style.

What was the Meiji Period?

Photograph portrait of the Emperor Meiji, c. 1880

Also known as the Meiji Restoration, the Meiji period was the era in the late 19th Century in which Japan returned to being ruled by an Emperor, known as the Emperor Meiji (‘meiji’ means ‘enlightened rule’).

Since around 1600, Japan had been ruled by a complex system known as the Tokugawa Shogunate, or simply the shogunate. It nominally had Emperors, but these were generally figureheads with no real power. Instead, Japan was controlled by the shogun, a military governor who ruled from the city of Edo (now called Tokyo). The shogunate era was often known as the ‘Edo Period’.

Pre-Meiji Japan was a feudal society. That is, land in Japan was divided up into large estates (called han) which were owned by daimyo (lords). Peasants could not own their own land, but merely borrow it from their lord in exchange for food and military service.

Japan operated according to a strict social hierarchy, running from the daimyo through to the samurai (the famous warrior class) and down to the peasants, artisans, and merchants.

And Japan under the shogunate was strictly isolationist, operating a policy known as sakoku. Japan’s ports were completely closed to foreign ships: nothing and no-one was permitted to come in or leave the islands.

The Meiji Emperor, upon acceding to the throne in 1868, ended all of this. He – with the help of some disgruntled daimyo lords – ended the shogunate and reformed Japan’s social structure and military.

He gradually weakened the powerful samurai class, freed peasants from bondage to their lord, built railroads, hospitals, and universities, began to trade with Europe and America, and fostered industrial growth based on the principles of the market economy.

Japan under the Emperor Meiji moved, in short, from being a feudal society to become a capitalist society.

Why was the Meiji period so important?

It’s because of these profound changes in economy, politics and society, that the Meiji period is commonly described as the period in which Japan entered modernity.

Or – more accurately, perhaps – we can think of it as the period in which modernity entered Japan.

Indeed, the end of Japanese isolation necessarily brought with it a huge influx of Western goods, people and culture. Western ‘experts’ arrived in the country to design Japan’s new railroads and factories, and to teach in Japan’s new universities.

This did not always happen by choice: Japan had initially opened its ports to America because it had been effectively forced to do so, by Commodore Matthew C. Perry in 1853. After Perry, the European powers had simply followed suit, threatening Japan with military force if they refused.

But while the opening of Japan to trade with the West brought Western culture to the islands, it also meant Japanese culture travelled the other way, to Europe and America.

Japanese goods were sold in Western markets for the first time, and they would quickly become highly fashionable. New demands for Japanese-made objects in the West would have a profound impact on the history of Japanese art and craft.

How did the Meiji period change Japanese art?

The Japanese Satsuma Pavilion at the 1867 Paris Exposition Universelle, the first time that Japan had exhibited at one of the 19th Century's Great Exhibitions.

In the face of these new global ties, not to mention the rapid changes in Japanese society, artists and craftsmen in Japan started to produce more works than ever before.

The Meiji period today is indeed remembered as a period of rapid expansion in artistic production, and the flourishing of older Japanese craft traditions.

The end of the feudal system in Japan had meant the end of an old system of artistic patronage in which makers were almost exclusively commissioned by their ruling samurai to make decorative pieces. Because the samurai were warriors, many of these pieces took the form of weaponry and armour.

Under the new system, Japanese craftsmen were granted more freedom, as they were designing pieces for the market – and for export – rather than according to a strict commission.

Meiji Japan was also keen to portray itself to the world as equal to the West in artistic and technological sophistication. in 1867, Japanese artists displayed their wares at the Exposition Universelle in Paris for the first time, and to great acclaim.

The new dialogue between Japan and the West also led to a cross-cultural confluence of styles and techniques. Japanese painters learnt new Western techniques, while Japanese craft, especially metalworking, was widely copied in the West (in a style known as japonism) and was an important influence on the development of the late 19th Century Art Nouveau.

Despite this cross-pollination, the art that developed during the Meiji period remained distinctly Japanese. Outlined below are the main characteristics and developments in the major Meiji period artistic mediums.

Meiji period painting and woodblock prints

It was during the Meiji period that Japanese art students first went to Europe to study Western painting, and developed a new style of painting based on these techniques, known as yoga (or ‘Western style’).

Yoga painting involved oil paints, canvas and watercolours, all techniques which had been developed in the West.

In reaction to yoga painting, a new, more traditionally Japanese style of painting emerged, known as nihonga (Japanese style) painting. This involved the application of natural pigments to silk and washi (Japanese paper), and emphasised block colours and shapes and altogether more two-dimensional compositions.

An example of yoga painting (left) versus nihonga painting (right). Left: Reminiscence of the Tempyo Era by Fujishima Takeji (1902); right: Jo no Mai (Noh Dance Prelude) by Uemura Shōen (1936). Note the differences in texture and composition, making the yoga painting appear more Western in style.

The development of nihonga as a form of opposition to the influence of the West was encouraged by a number of Japanese artists as well as influential critics, such as (ironically) the American lecturer Ernest Fenollosa, who taught at the University of Tokyo.

Indeed, the division between nihonga and yoga spoke to the uncertainty in Meiji society as a whole between embracing the West and rejecting it.

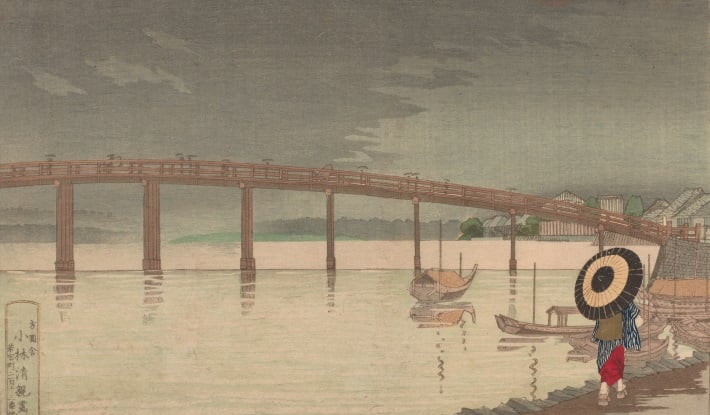

Woodblock printing also underwent transformation in the Meiji period, especially the traditional genre of ukiyo-e (literally, ‘pictures of the floating world’).

Ukiyo-e is some of the most recognisably Japanese art, normally taking the form of stylised images of kabuki actors, sumo wrestlers, flora, fauna, and erotic images. It was an ancient practice which had reached its peak in the 18th Century.

Its most famous practitioner was Hokusai, who, although dying shortly before the Meiji period began, is associated with Meiji Japan largely because of his popularity in the West during the era.

One important ukiyo-e artist in the period was the artist Kobayashi Kiyochika (1847–1915), who produced large-scale depictions of Tokyo’s modernisation (the main image in this article). These were unlike anything seen before in the genre, and point to the transformation of art in the Meiji period.

Meiji period bronze wares

Japanese Meiji period bronze incense burner in the shape of a daikon (a type of Japanese radish) with a mouse on top. The artist is unknown but note the fineness and detail of the bronze casting. Currently on display at the Linden Museum in Stuttgart, Germany.

In bronze-working, Meiji period craftsmen were newly empowered to attempt distinctive, innovative, and complex pieces.

Here, makers were influenced less by the West than by China, which had had a relationship with Japan stretching back thousands of years, far further than Japan’s recent association with Western powers.

Artistry in bronze-work reached new heights in the Meiji period, as a number of ‘metal-working’ schools developed, creating intricate pieces including vases, sculptures, teapots and incense burners.

Like Chinese pieces, these would often take nature as their inspiration, featuring images of flora and fauna as well as mythical animals like dragons.

Often these were applied with enamels, precious metals, or sometimes even hardstones (this was a technique known as ‘mixed metal’), and the best pieces were always meticulously-cast, intricate pieces with astonishingly realistic detailing.

Artists Suzuki Chokichi (1848-1919) and Kano Natsuo (1828-1898) were particular masters of the new techniques.

Meiji period cloisonné enamel

Detail from a cloisonne vase with birds and flowers, c. 1900, produced by the Ando Cloisonne workshop in Nagoya. © Walters Art Museum via Wikimedia Commons

The Meiji period was also known as the ‘Golden Age’ of cloisonné enamel, and with good reason: Japanese craftsmen in the period produced some of the finest, most complex works the world had ever seen.

The technique of cloisonné was introduced to Japan from China in the 1830s, and was initially used to decorate small items like jewellery and swords.

Japan’s Meiji period modernisation led to a vast increase not only in the number of enamellists, but in the range of enamelled objects. Its main centre was the city of Toshima (sometimes known in Japanese as ‘shippo-cho’, or ‘cloisonné-town’).

Cloisonné was an ideal medium for the kind of intricate, two-dimensional block-colour decoration which had come to be recognised as unmistakably Japanese, and artists experimented with new, complex techniques for achieving this effect.

The most important practitioners in Toshima were the artists Tsukamoto Kaisuke (1828-1887), and his pupil Hayashi Kodenji (1831-1915).

Kodenji would later found a new workshop in the town of Nagoya, at which other important artists such as Namikawa Yasuyuki (1845-1927) and Namikawa Sosuke (1847-1910) also worked.

It was in Nagoya that new enamelling techniques were developed, including ‘moriage’, when successive layers of enamel are applied to an object; and ‘plique-a-jour’ (known as shotai-jippo in Japanese), in which enamel is applied to a backing which is then dissolved, leaving behind a brilliant, luminescent object.

Plique-a-jour (shotai-jippo) enamel bowl by Namikawa Sosuke, for the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900. Note how there is no backing, and the light shines through the bowl like a stained glass piece. © Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

Enamel pieces were among the most impressive pieces seen by Westerners at the Great Exhibitions of the late 19th Century. Sir Rutherford Alcock, upon seeing these displays, wrote that ‘it is impossible not to be struck with admiration at the marvellous delicacy of execution and fertility of invention’.

The Victoria & Albert Museum immediately started acquiring enamel pieces from the Exhibitions, and today holds one of the world’s largest collections of Meiji period enamel.

Meiji period ceramics and porcelain

Detail from a Satsuma porcelain vase produced during the Japanese Meiji period, currently on display at the George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum. © Daderot via Wikimedia Commons

Most of the fine porcelain produced during the late 19th Century Meiji period was created in the region of Satsuma; to the point that Satsuma porcelain is practically synonymous with Japanese Meiji period ceramics.

Japan had had a long history of porcelain production, mostly based in the Hizen province. These so-called 'kakiemon' wares - mostly produced in the 17th and 18th Centuries - were widely admired in the West.

In the early 19th Century, however, kakiemon production had declined, and it was overtaken by porcelain and earthenware made in the Satsuma region.

The region of Satsuma was historically important, especially during the Meiji period: it was the first region to rebel against the shogunate and offer its support to the new Emperor.

Its porcelain had been important in the 17th Century, but underwent a revival following the expansion of production in the late 19th Century, during which time ceramicists perfected new overglaze techniques for decoration, as well as Satsuma porcelain’s distinctive ivory-coloured ground.

Most Satsuma wares were produced for export, and for this reason were decorated with images and subjects which its makers thought would be appealing to Westerners, including Japanese-style figures wearing kimonos; pagodas; flowers; and birds.

There were as many as twenty independent workshops operating out of the region in the late 19th Century, all of whom employed a large number of craftsmen to work on creating the decorations.

Satsuma porcelain from this period was sometimes criticised for being ‘over-elaborate’ in the quality of its decoration, and it is for this reason that we can see a shift in the early 20th Century towards more sparsely-decorated wares.

Because many of these were produced for the Western mass market, much Satsuma ware was of low-quality and has not survived until the present day; but there were nevertheless a number of masterpieces produced in the period.

Meiji period okimono and netsuke

Small ivory netsuke showing a mother with her child. © Wellcome Images via Wikimedia Commons

Okimono (‘decorative objects’) and netsuke (small carvings intended to be worn on the belt of a kimono) also enjoyed a newfound popularity in the West during the Meiji period, and are still even today some of the most widely collected Japanese antiques.

Okimono and netsuke are often confused, since they both generally take the form of small carvings (often in ivory but sometimes in bronze, wood, coral, shells and precious metals), which depict a wide range of subjects, including animals, mythical creatures, people, objects, flowers and fruit.

The major difference is that okimono are bigger and don’t contain holes which allow them to be fastened to a belt.

Both types of objects were produced on a large scale during the Meiji period, and in both cases their function was transformed: netsuke were no longer necessary as clothing accessories as Japan gradually adopted Western dress during the Meiji period, and okimono were no longer religious objects produced by artisans for their landlords as the feudal system ended.

Under the new market economy of the Meiji regime, okimono and netsuke carvers were free to experiment with more ‘secular’ subjects, and produced ever-more complex and precious objects, mostly for Western collectors.

Famous carvers of okimono and netsuke included Ishikawa Komei (1852-1913), who taught carving at the new Tokyo School of Art, which opened in 1889. His figures, and those of his school, are most recognisable for their high degree of naturalism and detail.

Meiji period okimono and netsuke range from small, delicate works to larger, more sculptural pieces.

Meiji period furniture, lacquerware and shibayama

Detail of a Japanese Meiji period ivory and mother-of-pearl inlaid hardwood cabinet

Finally, the Meiji period also saw an expansion in the production of furniture and lacquerware. These were especially popular in the West since their form and decoration was unlike anything seen before, and was seen as distinctively ‘Japanese’.

Indeed, the rich black lacquer which adorned most Japanese woodwork was so associated with the country that it was simply referred to as ‘japan’ (like ‘china’ for porcelain) in English. It was an ancient technique, involving the use of the resin from a tree native to East Asia, and remained a mystery to many in the West until the end of the 19th Century.

Furniture during the Meiji period grew taller and more impressive, as ceilings grew higher and Japan adapted to Western styles of living.

Lacquerwork also became more impressive, as craftsmen dabbled in new techniques of applying coloured lacquers, inlaying metals, and polishing lacquered surfaces down to a glossy, almost-mirrored finish.

Lacquer was not only applied to wooden furniture, but also to smaller decorative objects such as boxes, koro and even netsuke and okimono. Shibata Zeshin (1807–1891) was one of the most prominent lacquer artists of the period.

Top half of a tiered lacquer food box by Shibata Zeshin, inlaid with gold, silver and coloured lacquer, c. 1868-1890.

Lastly, the technique of shibayama became hugely popular during the Meiji period, again as a means of decorating furniture, vases, and small objects.

Shibayama refers to an inlay technique in which cut pieces of ivory, mother-of-pearl, coral, precious metal, wood and horn are inlaid onto a wooden or lacquer surface. The technique is similar to Western marquetry but produces a more three-dimensional, textured surface abnd often depicted more elaborate scenes.

Artistic development in shibayama occurred in the Meiji period, when makers started to use new materials, such as coloured enamels and precious metals, to make ever more complicated and sophisticated works.

When and why did the Meiji period end?

The Emperor Meiji died in 1912, bringing an end to this heady, vibrant period. He was succeeded by the new Emperor Taisho, who ushered the beginnings of liberal democracy in the country.

Japan during the 40-year Meiji period had undergone an enormous amount of change, socially, politically, and artistically. New styles and techniques developed, artists from previously separate crafts collaborated with each other, and production expanded on an unparalleled scale.

But it was also a period of great tension artistically: fierce battles raged over the contentious issue of Western influence on Japanese art; and for the first time in the country’s history, Japanese art was no longer only being made for Japanese consumers.

Japanese makers managed to weather the storm of these debates astonishingly effectively, creating art that was at once palatable to Western consumers, and at the same time respectful of Japanese tradition and heritage.

If there was any single artistic achievement of the Japanese Meiji period, it was this remarkable ability to balance tradition with innovation.

If you would like to have a look at our range of Japanese Meiji period antiques, please click here.