The story of the discovery of porcelain in Europe by scientists at Meissen is one that is often told in the history of European art, and for good reason: magic, imprisonment, diplomacy and theft are its major themes; a small medieval town in Germany its setting.

Cracking the secret to porcelain was a groundbreaking achievement in its day, but it’s one which runs the risk of overshadowing the other many achievements of the Meissen factory in the 18th Century and beyond.

The Meissen ceramicists not only discovered the formula for porcelain, but they used this formula to create some truly exceptional pieces of decorative art, sculpture, and tableware.

Where is Meissen?

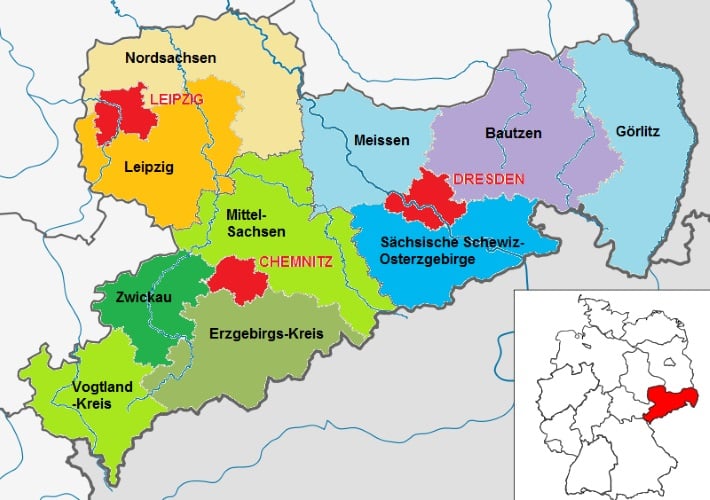

Map showing the location of Meissen with Saxony and Germany, c. 1900

The town of Meissen (also spelled Meißen) is a small town in Eastern Germany, a few miles north of Dresden. It is practically synonymous with porcelain – so much so that the name Meissen commonly refers both to the town and to the porcelain factory established there.

In the 18th Century, when the Meissen manufactory was founded, the town was part of the Electorate of Saxony, one of the member states of the Holy Roman Empire. It was, in the early 18th Century, under the rule of King Augustus II The Strong, who was also the King of Poland.

Meissen changed hands a number of times over the course of the next two centuries, thanks to the Seven Years’ War and the Napoleonic invasions of the early 1800s. Throughout this time Meissen remained one of the most important towns in the region, in no small part thanks to its highly influential porcelain factory.

A view of the Cathedral in Meissen, Germany. © Avda via Wikimedia Commons.

When was Meissen founded?

The factory of Meissen officially began production of porcelain on 28 March 1709; but the story which had allowed them to reach that point was one which dated back thousands of years.

Chinese porcelain in Europe

Pair of blue and white Chiense porcelain vases from the Ming Dynasty, now in the British Museum. © Daderot via Wikimedia Commons

Porcelain had been being produced in China for thousands of years: the exact start date is impossible to pinpoint since archaeological finds have dated porcelain-like products as far back as 1200 BC.

Porcelain as we would recognise it today, however, was first produced on a large scale during the Chinese Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD).

From this time Chinese porcelain (or china, as it was more simply known) had been slowly entering the European market, and with it capturing the European imagination.

In the Middle Ages, porcelain from China was imported at great cost and made available at extremely high prices. It was for this reason that porcelain was also informally known as ‘white gold’.

The dearness of imported porcelain, and its rarity, had kickstarted a race among Europe’s craftsmen to discover the secret formula. Until that point, European ceramicists had only been able to make second-rate earthenware and ‘soft-paste’ porcelain.

Chinese ‘hard-paste’ porcelain, by contrast, was durable, translucent, and could withstand heat and water.

The discovery of porcelain in Meissen

Red stoneware 'Bottgerware' teapot in the Chinese style, c. 1710, at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremburg

Rulers from all over the European continent had, unsuccessfully, sponsored efforts to produce this kind of hard-paste porcelain in their own lands.

King Augustus II, Elector of Saxony and therefore the ruler of Meissen, was particularly enamoured with Chinese porcelain, possessing a personal collection of over 20,000 Chinese pieces. For him, porcelain was a symbol of his wealth and power, and it was imperative that he should be the first ruler to crack the secret.

The breakthrough finally came around the year 1700 when Augustus became aware of experiments being conducted by a young alchemist named Johann Friedrich Böttger (1682-1719).

Böttger had boasted that he had discovered the secret to alchemy, that is, to produce gold out of worthless materials. Augustus demanded that he perform this feat for him, and had the young chemist imprisoned in a dungeon until he could make gold.

By 1704, Augustus had become frustrated with Böttger’s lack of progress, and appointed the mathematician Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus (1651-1708). Eventually (and reluctantly) Böttger abandoned his pursuit of gold and took up Tschirnhaus’s experiments with making porcelain.

Tschirnhaus, with Böttger as his assistant, quickly discovered that the secret to making porcelain did not lie only in the ingredients being used, as so many had assumed, but in the temperatures at which the clay was fired.

Their first experiments had resulted in the production of red stoneware (later known as Böttgerware, pictured above), but by 1708 they were producing true white hard-paste porcelain.

Although there is some debate over whether it was Tschirnhaus or Böttger who first cracked the secret to porcelain (some have even suggested it was invented in England first!), what we do know is that in 1708 Tschirnhaus suddenly died, leaving Böttger in sole charge of porcelain production in Meissen.

It was not until the following year, in 1710, that Böttger officially received the royal decree which would establish the Meissen factory.

How is Meissen porcelain made?

The secret to porcelain production, as Böttger discovered, lay in firing a special type of clay known as kaolin (china-clay) at around 1,200 degrees Celsius.

Luckily for Böttger, there was a natural abundance of the mineral in the countryside around Meissen; and its discovery accelerated the development of Meissen porcelain.

In European porcelain-production, kaolin is mixed with a variety of different materials: bone-ash, feldspar, quartz and even glass are all occasionally used to produce porcelain.

The traditional and original Meissen method, however, was to use a mixture of kaolin and alabaster. It was a closely-guarded secret for a number of years, before industrial spies from other factories in Europe finally discovered the secret.

By the middle of the century, porcelain factories in Vienna, Sevres, Venice, Florence, and Staffordshire were all using Meissen’s hard-paste formula.

What is Meissen porcelain?

Meissen's famed 'Half Figure' porcelain tea set, c. 1723-34. © Bonhams

Meissen porcelain has an extremely distinctive form of decoration, developed throughout the 18th Century.

When antiques collectors and experts talk, therefore, of ‘Meissen’ porcelain, they are not solely talking about all porcelain made in the town of Meissen, but porcelain which has its own look, feel and style.

Indeed, once the Meissen ceramicists had mastered making porcelain, the next step was to master decorating it. Since there were no available European examples to base their work on, they started, naturally, by imitating Chinese pieces.

Early Meissen porcelain decoration was largely completed by the painter they recruited from Vienna in 1720, Johann Gregorius Höroldt (1696-1775), who developed a set of sixteen enamel colours – which are still the basic colours used in porcelain-making today.

It was from this crucial period, in the 1720s, that Meissen gained its reputation across the world for fine porcelain.

Höroldt’s pieces were largely completed in the chinoiserie style (that is, taking after Chinese pieces) but he also developed a range of wares which took inspiration from Japanese ceramics. These were known, confusingly, as Indianische Blumen, or 'Indian flowers'.

Sometimes Höroldt and his craftsmen combined Japanese and Chinese stylings, as in the below example.

Meissen porcelain teapot, 1724-1725 at the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Notice the Chinese-style drawing inside the cartouche on the teapot, with the Japanese-style flowers (Indianische Blumen) painted in purple around.

One of Höroldt’s assistants was a young sculptor named Johann Joachim Kändler (1706-1775), an artist who is now remembered as having led Meissen into its mid-18th Century Golden Age.

Kändler eventually took over from Höroldt around 1733, and his early pieces clearly bear the influence of the great chinoiserie expert.

As more time passed, Kändler developed his own virtuosic style. Today Kändler is remembered as Meissen’s most important and highly revered modeller.

Kändler’s genius was to move Meissen away from imitation Chinese works, and to align Meissen’s production with the emerging, fashionable Rococo style.

Most of Meissen’s most famous pieces were produced under Kändler. Some of Meissen’s most distinctive 18th Century porcelain products are outlined below.

Meissen animal figures

Meissen's 'Billy Goat', modelled by J.J Kandler c. 1732, on display at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London. Note the unusual large size and extremely high quality detailing on this astonishing piece of sculptural work

Some of Kändler’s most recognisable figures were the range of animal figures he produced for a variety of important clients.

Interestingly, these figures were largely intended as tableware. Their designs took after the designs of sugar moulds, devices for displaying sugar on grand dining tables.

Sugar would be pressed into a mould – normally in the shape of an animal – and placed on a dining table to be consumed. Early Meissen porcelain figures replicated the designs of these moulds, but because they were more durable, they ended up taking on a life of their own and becoming collectable in their own right.

King Augustus II, founder of Meissen, was particularly fond of these figures. He consciously cultivated an image of being learned and scientific, and kept a large menagerie of exotic animals for display and study.

Kändler’s animal figures were unusually accurate and naturalistic in their representation, and were especially exceptional for the high level of detailing – given that porcelain sculpture was such a new craft in the period.

Meissen porcelain figures

Group of comedia dell'arte figures by Kandler for Meissen, c. 1735-1744. © Sean Pasathema via Wikimedia Commons

Meissen under Kändler also developed a series of human figures which were extremely popular among Europe’s elite, as well as among collectors today.

These figures had all the attributes – lightness, grace, humour, and exuberance – of the very best Rococo period art.

Kändler in particular was inspired by the famous Italian comedia dell’arte form of theatre, and many of his figures were stock characters in the comedia: harlequins, foolish old men, devious servants.

It was the fluency and vibrancy of the the Meissen comedia figures which showed the full range of Kändler’s extraordinary abilities.

By the 1750s, Kändler was even experimenting with combining his human and animal figures, resulting in his famed ‘monkey orchestra’, one of the most recognisable Meissen pieces created.

Meissen's famous 'monkey band', featuring a variety of monkeys in 18th Century dress

Meissen dinnerware

As well as decorative sculpture, Meissen was famous for a number of objects which, although still astonishingly artistic, were more functional in nature.

Meissen, for example, produced a wide range of tableware across the 18th and 19th Centuries.

Perhaps the most famous Meissen dinner service – again produced under Kändler – was the ‘Swan Service’ created for Heinrich von Brühl, the First Minister of the Electorate of Saxony, between 1737 and 1742.

The set consists of over 2,000 individual pieces and featured decorations inspired by natural forms, botany, and water.

Meissen porcelain terrine from the 'Swan Service'. Note the distinctive Meissen figures at the top and sides of the piece, as well as the Rococo shell elements

Meissen porcelain candelabra and vases

Meissen also produced porcelain candelabra and vases across the 18th and 19th Centuries, again employing many of the same stylistic flourishes as in their tableware and figures.

Meissen even produced entire chandeliers made from porcelain throughout this period.

These works used the same enamel colourings, curving shapes and flamboyant designs as many of their other famous Rococo style pieces.

Meissen Two-Handled Urn, 1814-60. © Milwaukee Art Museum. Photo credit: John R. Glembin.

Later Meissen works

Production at Meissen continued after Kändler, and throughout the 19th and 20th Centuries, right through to the present day.

The works produced by Meissen never, however, quite matched the artistic triumph of its Rococo heyday under Kändler.

Indeed, many of the works produced in the 19th and 20th Centuries by Meissen were revivals of old models introduced under Kändler – simply because they were so popular among wealthy European clients.

That said, 19th Century Meissen did experiment with new forms and styles, most notably during the Art Nouveau period at the end of the century. Meissen also adopted the nascent Art Deco style in the early 20th Century.

How to identify Meissen porcelain

Chart showing the different underglaze marks used by Meissen across the 18th Century

The classic identification mark for Meissen is the blue underglaze crossed swords mark, pictured above. It should normally be found on the underside of any Meissen piece.

However, Meissen only really started using the underglaze mark from the 1770s; before this, Meissen pieces were either marked with an ‘AR’ (for Augustus Rex) or not at all.

So not all genuine Meissen pieces bear the crossed sword marks; conversely, not all pieces with the crossed sword mark are genuine Meissen.

The best way to identify genuine Meissen (as with most antiques), then, is by gauging the overall quality of the piece: the brightness of the decoration, the brilliance of the gilding, and the feel, weight and detail of the piece.

There are also, in addition, a number of clues which give away Meissen pieces: very early pieces should be greyish-white in colour, but after about 1720 (when Höroldt changed Meissen’s formula), they should be a brilliant white, with a bright, lustrous glaze.

Real Meissen pieces should also be distinctive in style: that is, they should either have Rococo elements, or Baroque elements, but never both together.

One further complication, however, is that by the 19th Century, copies of Meissen pieces were as high-quality as the ‘real’ thing. Identifying Meissen by quality alone is no longer sufficient.

In general, then, identifying Meissen is just like identifying good quality porcelain overall: it’s more a question of how the piece feels than what name is attached to it.

Meissen vs Dresden porcelain

There is also a certain amount of confusion over the difference between Meissen porcelain and Dresden porcelain, which is hardly surprising given the proximity of the two towns. Pieces which are actually the work of Dresden craftsmen are often wrongly described as Meissen, and vice-versa.

One thing to remember here is that Dresden did not begin manufacturing its own porcelain until the 19th Century: any piece which is labelled Dresden from earlier is likely to have been manufactured in Meissen, but decorated in Dresden.

Because Meissen had the monopoly on porcelain for much of the 18th Century, their pieces were hugely expensive. It was much cheaper for many buyers around Europe, then, to buy undecorated, plain Meissen pieces and have them painted in workshops locally.

A wide variety of workshops in Dresden sprang up across the 18th Century, dedicated solely to the painting of Meissen pieces.

As the market for Dresden-decorated pieces grew (and the secret formula for porcelain was revealed), Dresden developed its own distinct facilities for producing porcelain in the 19th Century.

It is because Dresden largely grew out of Meissen that the two are often confused.

Meissen today

There is still a porcelain factory in Meissen today (although it has moved from its original 18th Century location) which still continues to produce porcelain and ceramic products.

As for Meissen’s antique pieces, most of these are split between private collections and large public ones.

The Victoria & Albert Museum has a breathtaking collection of some of the very finest Meissen pieces, which can be viewed in the ceramics rooms of its flagship London gallery. In Germany, the Zwinger Colllection in Dresden possesses many of Kändler’s animal figures.

There are also many Meissen pieces traded on the private market which range from the very affordable to the astonishingly expensive (for the earlier, more important pieces)

The 21st Century trade in Meissen is just as vibrant as it was in the 18th Century. There is perhaps no greater testament to the quality and beauty of Meissen porcelain than this fact.