In the 19th Century, most Europeans had never been to the region we now know as the Middle East.

For most, the Middle East was a kind of mystery, a blank canvas on which to project a wild dream.

Europeans wanted to believe that the Middle East was a region of exotic luxuriance, sensual richness and forbidden pleasures, a place quite separate to their own.

The 19th Century Middle East was, in short, a fantasy. And although the region was slowly but surely coming into reach across the 19th Century – thanks to advances in travel, communications, and scholarly study – the people who did venture there indulged this fantasy to the extreme.

The so-called ‘Orientalist’ painters conjured exquisite images of rich, bountiful landscapes, sensory and erotic delights, and vivid emotions.

The Middle East depicted in the Orientalist paintings of the 19th Century was simultaneously real and not real: viewers knew that the place existed, somewhere; and yet every element of it was fantastical, as if belonging to a different world entirely.

What does ‘Orientalist’ mean?

Orientalism is a term with a wide definition. It is used very generally to denote the study and depiction of the ‘Orient’ by the ‘West’.

The ‘Orient’ is itself an extremely broad term, and can refer to anywhere East of Europe – be it Turkey, India, China, or Japan.

In art, however, Orientalism is more commonly used specifically to refer to a style of painting which developed in the 19th Century and which depicted the region of the world now known as the Middle East: the regions of West Asia, North Africa and the south-eastern tip of Europe.

Orientalist painting flourished within Europe’s artistic academies in the 19th Century, and in this sense was linked to the tradition of Academic art.

The Orientalist style of painting also had a less profound – but still important – influence on other art and design media, including sculpture, architecture and the decorative arts, all of which can be described as having a distinctive ‘Orientalist’ style of their own.

When did Orientalist art begin?

European trade and travel with the Middle East had dated back thousands of years, but fascination with the region took off properly at the turn of the 19th Century.

A number of developments in this crucial period helped to generate the interest in the Middle East which would be expressed in Orientalist art.

In politics, Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798 kickstarted the new academic study of the country.

His invasion was not merely a military one, but a scientific and intellectual one, taking with him a band of scientists, archaeologists and writers known as savants. His aim was not only to rule the country, but to study its history and culture.

Notably, Napoleon also employed his court painters to create stirring images of him in action in Egypt, as in the below painting by his favourite court artist Antoine-Jean Gros (1771-1835).

Bonaparte Visiting the Plague Victims of Jaffa (1804) by Antoine-Jean Gros

Archaeology in particular helped to change Europeans’ perception of the Orient. Like it had done with Greece and Rome in the 18th Century, archaeology in Egypt and Mesopotamia (modern-day Turkey, Iraq, and Syria), heightened European’s interest in the region via the grandeur of its ancient civilisations.

Moreover, travels and excavations in these regions (notably at Babylon in 1815 and Nineveh in 1842) stunned the world by uncovering the remnants of a great civilisation that was far older – and in many ways far more impressive – than Greece and Rome.

Travel, culture, and the grandeur of ancient civilizations – these were all also themes that animated the group of late 18th and early 19th Century artists, painters, and thinkers known as the Romantics.

Lord Byron, perhaps the archetypal Romantic, had spent much of his adult life travelling in Greece and Turkey and was influential in introducing his readers to the region then known as the ‘Near East’.

Romanticism was attracted the exotic dress, military heroism and art of the people who lived there, many of the themes which animated the Orientalist painters.

Fascination with the Middle East emerged, then, from a combination of political, intellectual, and literary forces. It was this fascination which would go on to inspire the Orientalist painters.

Although they grew out of the Romantic tradition of painting, Orientalist artists would, over the course of the 19th Century, develop their own distinct style of painting.

The story of Orientalist art is the story of the slow development of a distinct genre which would culminate eventually in the formation of the French Society of Orientalist Painters in 1893, with Jean-Léon Gérôme, one of the most prominent in the movement, as its president.

What were the major features of Orientalist painting?

Although Orientalist painters were all inspired by what they saw as the beauty of the Middle East, several of them never actually travelled there, instead relying on descriptions they had read in travelogues and in literature.

Many, however, of the most important painters did travel themselves, and what they painted was based on the sketches they had made while they were there, and on the objects they brought back with them.

Orientalist paintings therefore took the form of landscapes, archaeological painting, and, most commonly, genre scenes depicting ordinary Middle Eastern people in everyday settings.

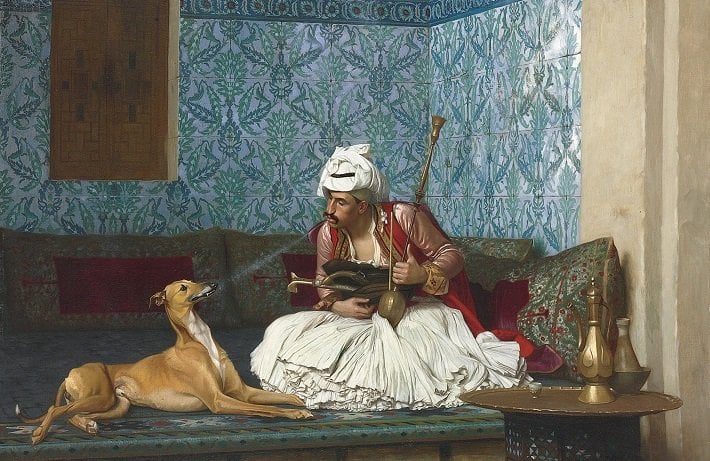

Une Plaisanterie (A Joke) (1882) by Jean-Léon Gérôme, depicting a playful moment between a Turkish man and his dog

And yet, though these paintings were depictions of ordinary people going about their daily lives, they were sensationally exotic.

Exoticism is perhaps the defining characteristic of Orientalist art: its subjects are stereotyped, its details are exaggerated, the sensory worlds of tastes and smells are passionately invoked. In their vivid colour and exceptional detail, the best Orientalist paintings have almost photographic qualities.

As well as exoticism, eroticism is an important part of much Orientalist art. Female subjects were often nude, and in sensual poses for the titillation of their Western viewers.

Of course, however, Orientalist art covers a broad range of different kinds of paintings made by artists from all over Europe – Britain, France, and Germany especially – each with their own distinct style.

Some of the differences between Orientalist painting in Britain and France are outlined below.

French Orientalist painting

France was the birthplace of Orientalist painting. Romantic painters such as Eugene Delacroix created the first celebrated depictions of the Orient with his grand, gory battle scenes.

Les Fanatiques de Tanger (1838) by Delacroix, depicting a gruesome scene of religious violence in Morrocco

But as the century progressed, French Orientalist artists increasingly took up genre painting, which would become the major form of French Orientalist art.

The subjects of French Orientalist art were engaged in routine activities: eating, drinking, bathing, shopping, and praying.

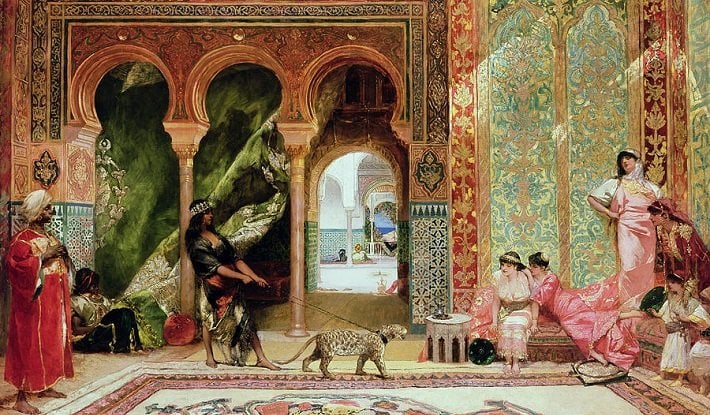

French Orientalist works tended also to be more explicitly erotic than their other European counterparts. Indeed, the harem – the part of a Middle Eastern palace reserved for the owner’s concubines – was an extremely common setting for Orientalist artwork.

Male painters were not allowed to enter harems, and so harem paintings were mostly the result of the artists’ imagination. It's for this reason that many harem paintings have almost voyeuristic qualities.

Le Harem du Palais by Gustave Boulanger (1824-1888). Note the positioning of the artist relative to the scene, giving the painting a voyeuristic quality, as the observer is viewing the scene from afar

Likewise, paintings of lounging odalisques (female servants in harems), although again common in Orientalist art, were often created using French models.

British Orientalist painting

British Orientalist genre painting, on the other hand, tended to be less gaudy and sexually explicit than French art.

Where women or the harem were the subjects, they tended (unlike in French painting) to be fully clothed, and in possession of a kind of Victorian moral earnestness. Prominent British painter John Frederick Lewis (1804-1876), for example, used his wife as his model for his harem paintings.

Perhaps this was a result of Victorian Britain’s tighter control over sexual morality; but perhaps it was also a simple consequence of British painters’ stricter adherence to their sketches.

This was as true of genre painting as it was of landscape and topographical painting. The forms of domestic architecture – the distinctive design of Turkish and Arabic homes, for example – is a recurring theme in British genre painting of the period.

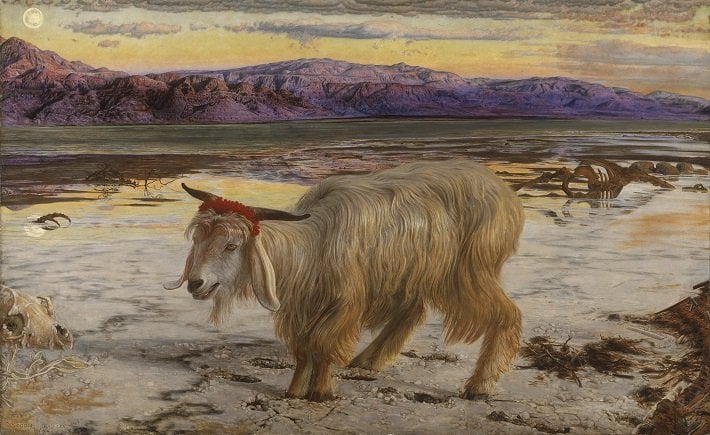

One important strand of British Orientalist art which did allow itself to diverge from the artists’ sketches was religious in character.

Because the Middle East had long been identified as the land of the Bible, painters used the landscapes they had seen on their travels as settings for paintings of religious scenes, as in the below example:

The Scapegoat (1854-56) by William Holman Hunt, depicting the famous 'scapegoat' described in the Book of Leviticus in the Old Testament of the Bible

Who were the major Orientalist artists?

The earliest painter to become prominent through a distinctly ‘Orientalist’ style was Eugene Delacroix (1798-1863), whose painting The Women of Algiers (1834) is one of the most celebrated early works of Orientalist art.

At the same time, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867), Napoleon’s court painter and the artist behind this article’s main image, pioneered Orientalism from within a stricter Neoclassical tradition.

His pupil Théodore Chassériau (1819-1856) developed the style in France, together with artists such as Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps (1803–1860).

In France, however, it would be Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904) who would become most associated with the Orientalist ‘movement’ later in the 19th Century. His work is often unapologetically sensual and erotic, and sought to capture what he saw as the high drama and passion of Oriental life.

La Grande Piscine de Brousse (1885) by Jean-Léon Gérôme, depicting a bath in the Turkish town of Bursa

In Britain, it was Sir David Wilkie (1785-1841) who first ventured to the Middle East to paint portraits of the Sultans and Ottoman military commanders of Syria, Egypt and Jerusalem.

He was later followed by John Frederick Lewis (1804-1876), perhaps the most prominent of the British Orientalist painters, renowned in particular for his extraordinary attention to detail and realism. He lived in Cairo from 1841-1851.

A Lady Receiving Visitors (The Reception) by John Frederick Lewis. Note the extraordinary detailing on the windows, walls and ceiling of the building depicted here. The house in this scene was based on his Lewis's own house in Cairo.

Also important in British Orientalism was David Roberts (1796-1864) and later William Holman Hunt (1827–1910). Holman Hunt was also famous for forming the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, which would become hugely important in the history of British art.

Elsewhere in Europe, painters such as Ferdinand Max Bredt (German, 1860-1921) Gustav Bauernfeind (German, 1848-1904), Ludwig Deutsch (Austrian, 1855-1935), and Rudolf Ernst (Austrian, 1854-1932) all also gained a following for their imaginative, detailed, sensuous depictions of the Orient in bold, vivid colours.

How else did Orientalism influence art?

Painting was not the only medium to have been influenced by the Oriental style.

The new interest in the Middle East in the 19th Century, and the new fashion for the visual culture of the Orient gave rise to developments in a number of different artistic media.

Orientalist sculpture

Pair of large patinated bronze busts by Élé Guillemin, depicting an Oriental man and woman

Orientalist sculpture was often taken up by many of the same painters who specialised in Orientalist works.

A notable example is Jean-Léon Gérôme, who took up sculpture late in his career but produced some impressive bronzes.

Elsewhere, French sculptors such as Élé Guillemin (1841-1907) and Jean Jules Salmson (1823-1902) specialised in sculpting Middle Eastern subject matter.

The Orientalist style was particularly associated with the cold-painted bronze works of prestigious Austrian artist Frans Xaver Bergman (1861-1936).

Orientalist architecture

The Brighton Royal Pavilion in England. © Qmin via Wikimedia Commons

Orientalism had a less profound impact on architecture, but there are a few notable examples, most impressively the Brighton Pavilion (pictured above), the seaside pleasure palace constructed for King George IV of England in the early 19th Century.

The Pavilion is a complex mix of different Oriental styles, including Islamic ones, but also drew inspiration from India, China and Japan.

Orientalist interiors also became popular in Britain during the later part of the 19th Century: the most famous example of an Oriental-inspired interior was the London residence of artist Frederic Leighton (1830-1896), now open to the public as Leighton House Museum.

Orientalist decorative arts

Orientalism’s influence on the decorative arts could be sensed more keenly in the 19th Century, and were at least in part born out of a slightly different tradition to Orientalist painting.

Just as there was a fashion for chinoiserie in the 18th Century in Europe, there could also be said to have been a similar fashion for Turquerie dating as far back as the 15th Century, and which attempted to imitate the artistic styles of the Ottoman Empire.

An important maker of Islamic-style decorative art in the later 19th Century was the French potter Théodore Deck (1823-1891), highly esteemed for his Orientalist faience works.

The important Orientalist painter Rudolf Ernst, discussed above, also started a ceramics workshop in Fontenay-aux-Roses in 1905 dedicated to producing Oriental-themed faience tiles.

Where can one see Orientalist art today?

Several of the world’s finest galleries and museums display 19th Century Orientalist paintings.

The Louvre in France contains most of the best-known French Orientalist work, while the Tate in Britain owns the finest British examples. Much Orientalist art is also owned privately.

As well as still being on display in galleries globally, Orientalist art also lives on in another, more profound sense: by continuing to influence the way artists and the public think about, view and depict the Middle East.

Oriental subject matter, for example, continued to be important for several of the most well-known ‘modern’ artists of the 20th Century, including Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Henri Matisse, Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky.

But it could even be argued that the work of the 19th Century Orientalists influences the way that we in the present day think about and depict the Middle East region. This indeed was the argument of cultural critic Edward Said’s famous book Orientalism (1978), to which we owe the name of the genre.

The Orientalist painters’ exotic fantasies of the East live on: in our minds as well as in our art.