It is hard to think of a term that is used so widely and so wantonly in the world of arts and antiques. One need only step into a gallery or open the first page of an art history book or catalogue to be inundated with every expert and keen amateur telling you why a certain painting or object, is Classical, Neo-classical, Neo-classical revival, Neo-classical Empire-style, and so on and so forth. Everyone knows it when they see it, but few can explain it. So, what exactly is ‘the Classical,’ what makes something ‘Classical’ or ‘Classicizing’, and why does it feel like all art is forever fated to live under the shadow, or light, of the Classical period? Here we aim to show you why ‘Classical’ is a term never to be afraid of.

What do we even mean by ‘Classical?’

If you were to pick any place at any time that you would associate most strongly with the term ‘Classical’ it would probably be Athens, or Ancient Rome. And you’d be right to do so. While ‘Classic’ and ‘Classical’ are terms that have a wide variety of uses and contexts and are words so embodied in our language they can refer to a whole multitude of things, in their original context they meant the Greece and Rome of antiquity.

Classics as a discipline is the study of Ancient Greece and Rome, from c.800 BC to c.400 AD, give or take a couple centuries. Classical, as an art style, covers everything from the early Classical c.480 BC to the fall of Rome in 410 AD. After what we call the ‘Archaic,’ the Classical style emerged, and remained the dominant style for the rest of antiquity, although scholars like to split it further into Early, High, Hellenistic, and Roman.

Generally, we all have a sense of the importance of Greece and Rome as the cradle of Western Civilisation, the fountainhead from which Europe, the Renaissance, and, effectively, the entire Modern World springs.

What is less well known, however, is that until c.500 BC, there was very little sense that Europe was really something separate from the wider world. Rome was a very small city-state in its infancy, and Greece was only a small part of a far larger world and culture that spanned the Eastern Mediterranean and extended into the East. Greece was a place of minimal importance compared to the vast network of Egypt, Persia, Cyprus, the Levant, and the Middle East.

In the Classical period all this changed. The Greeks (specifically the Athenians) fought off the Persian invaders at the Battle of Marathon, and in the next few years they revolutionised the Mediterranean world, distinguishing themselves from all other nations and cultures, and creating an art movement to go with it that has endured, and thrived, right up until the present day.

The Revolution from the Archaic to the Early Classical, c.480 BC, in Ancient Athens

Greek art is instantly recognisable. The Elgin Marbles, for example, are some of the best-known artefacts in the world. But Greek art didn’t always look like this. For a long time, it looked very close to Cypriot, Egyptian, even Oriental art. Dedications from the 6th century BC at Delphi, the religious centre of the Greek world demonstrate this. There are sphinxes that look positively Egyptian, and gilt ivory statues of gods that wouldn’t look out of place in Ancient Persia.

A selection of major Archaic sculptures: The Naxian Sphinx, c.560 BC from Delphi. The Anavyssos Kouros, c.530 BC, and Antenor’s Kore, c.520 BC, both by Attic artists. These artworks – all Greek – bear a great deal of similarity to Ancient Egyptian art and Persian Art, and are very different to Classical Greek art.

Because of this, scholars split Greek art into the ‘Archaic’ and the ‘Classical.’ Archaic art developed organically in the context of the wider Mediterranean and in co-operation with wider artistic movement. While some Archaic art does look very Greek to us, particularly vase painting, which probably reached its peak in the late 500s BC, it was decidedly Oriental. Stylised, as opposed to naturalistic, defined by pattern, rather than a canon that looked to nature, and aimed to represent it in an idealised manner.

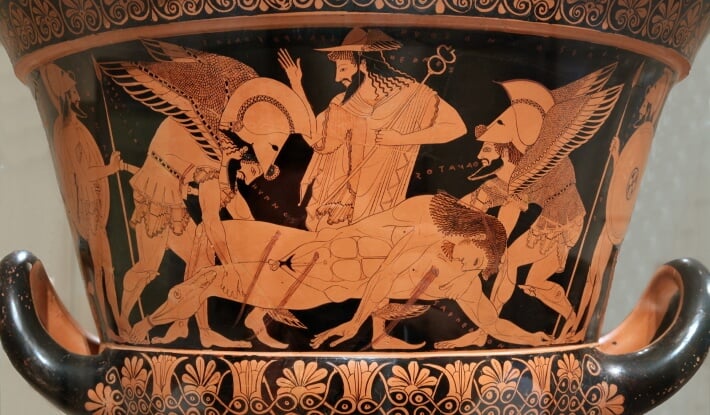

The Death of Sarpedon from the Euphronios Krater, c.510 BC, one of the finest of all Greek Vases, dating to the late Archaic period. Unlike sculpture and architecture, Greek vase painting reached its zenith in the late 500s BC, before Classical times, with the work of artists such as Exekias.

The ‘Classical’ first appeared in the aftermath of the Battle of Marathon and the first stage of the Persian wars. It is hard to emphasize quite how quickly Greek art and sculpture changed. In a matter of a decade or two Greek sculptures transformed from the stiff, rigid, unrealistic ‘kouros’ and ‘kore’ statue types, into incredible dynamic works of art, exemplified in masterpieces such as the Artemision Zeus, Myron’s Discobolus and the Riace Bronzes.

Masterpieces of the Early Classical Period. The Artemision Zeus, Myron’s Discobolus, and Riace Bronze A, all c.480-470 BC.

A telling example of the change can be seen at a lesser-known archaeological site, that of the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina. Here, two warriors, shown in the same pose: wounded, laid low, and close to death, are depicted in totally different ways.

The first sits almost upright, with the typical ‘Archaic smile,’ which could not be more out of place. His hair is in Eastern style curls, his muscles somewhat realistic, but lacking any sense of torsion and strain. He looks out at us as if reclining at a banquet: apart from the arrow sticking out of his chest. He is late Archaic.

The other, made only a year or two later, is fully Classical. His anatomy is significantly more realistic. His body twists, and his musculature reflects the torsion in his body. Gone is the Archaic smile, and his mood matches his circumstance. The artist took the time to properly observe the anatomy, and he cast off old conventions of representation, embracing new ones that looked to nature, but also depicted nature in a heroic, proud, masculine Greek fashion.

Two dying warriors from the Temple of Aphaia, Aegina, c.480-470 BC Top: Archaic. Below: Classical.

To draw together the key concepts of the Early Classical period, the following is a good summary of what it entailed:

- A conscious rejection of Eastern and Persian art and dress – we are Greek, and to be Greek is something different, something heroic, and something better.

- A clear focus on realism. Paying attention to anatomy, and infusing art and sculpture with concepts such as proportion, symmetry, that is to say: commensurability, whereby all parts of a figure are in harmony which each other, balance, and, where possible, naturalistic movement.

- A mode of masculine self-representation that displayed confidence, military strength, discipline, and athletic prowess.

- A shift from marble as the main material, to bronze, where a greater range of motion was possible, and the artist could be significantly more ambitious in their compositions.

The High Classical in Athens, c.460-420BC

This early Classical period we have looked at above is often referred to as ‘Severe.’ As one can detect from the works shown, it was very masculine, highly focused on realism, and lacking some of the grace, softness, and beauty of more well-known and popular Classical works. Female figures lacked the charm and sensuality of what we call ‘High Classical’ works.

The Athenians pioneered the High Classical style in the mid-5th century BC, in the time of Pericles, a leading figure of Democratic Athens. At this time the Athenians became the dominant power in the Aegean Ocean, and heavily taxed other city-states that were part of the Delian league, an alliance of Greeks against the Persians. It spent a great deal of its newfound wealth on the Acropolis, funding grand business plans and artistic projects, such as the Parthenon.

A painting of the Athenian Acropolis in 1863, by Rudolph Müller. Periclean Athens in the mid-5th Century BC is where the High Classical period mostly took place, and where buildings like the Parthenon set new standards for art and architecture that lasted for thousands of years.

While the High Classical style they developed built on the early, Severe period, it altered it in subtle but important ways. It was realistic, but with a heightened sense of ‘realism.’ Canons of proportion developed, specific poses emerged, and attempts were made at depicting the ‘ideal’ warrior.

Female statues also became more elegant. They kept their Classical, tied-up, shorter hairstyles, and simpler dress, but the sensual ‘wet’ style emerged, displayed most famously by the goddess statues from the Parthenon, where their translucent dress highlights and accentuates their highly feminine forms.

Three goddesses from the East Pediment of the Parthenon, c.440 BC, in the British Museum, London. The most famous and beautiful of all the Elgin Marbles. The ‘wet’ style can clearly be seen on the body of the reclining goddess who is probably Aphrodite, goddess of love and beauty.

The Hellenistic Style, c.330-100 BC

No style ever stays the same, and in the Hellenistic period, c.330 BC onwards., the Classical style saw its first seismic shift. At the end of the Classical period, c.330 BC, Philip of Macedon united the Greek states, which had been constantly bickering and waging war against each other, and his son Alexander the Great then used this united Greek force to launch a huge military campaign that defeated the Persian Empire.

After this, Greek culture was spread across all the nation states that had been formerly held together by the Persians, in what is known as the ‘Hellenistic’ era. In the Hellenistic period the traditional Classical canon was broken. Figures became more slender, and their musculature altered. Often, it became more floral, more expressive, less bound by convention, freer to depict vulnerable or weaker male figures, and more prone to show highly emotional moments, often more tragic, and less dignified and heroic.

The Laocoon, c.30 BC – 70 AD, Vatican Museums, a Hellenistic sculpture. The Hellenistic period was defined by depictions of much more extreme emotion and grief, like here, where Laocoon and his sons are killed by serpents sent by Athena.

The Late Classical period in Rome, c.100 BC – 400 AD

Rome took over as the centre of the Classical world in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, when it sacked Carthage, subdued the Greek world and established itself as the dominant force in the Mediterranean. Their art appropriated a whole host of styles from the Greeks, from Archaic to Hellenistic, and added new styles of their own – particularly styles of painting and mosaics that are preserved at Pompeii.

It is often said that Rome conquered Greece militarily, but culturally that Greece conquered Rome. The art, philosophy, architecture, and mythology of Greece became that of Rome, and Rome became the successors of Greece, admiring its art, and creating art of its own that copied various Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic styles.

The Romans skill in engineering allowed them to surpass the Greeks architecturally, with marvels such as the Pantheon, the Colosseum, the Mausoleum of Hadrian - now the Castel St. Angelo - and a huge complex of buildings and arches in the Roman Forum. Their public sculpture involved adopting the classical style to promote the public image of leaders such as Emperors and generals.

A statue of the first Roman Emperor, Augustus, 1st Century BC; Roman sculpture saw the Classical style put in service of promoting the public image of emperors and generals.

The essence of the Classical style across these periods: the high points of Greek civilisation in the 5th and 4th centuries BC, and the glory days of Rome right up until its eventual demise at the hands of the Huns in 410 AD, is that it represented and embodied in an artistic framework the hopes, ambitions, and dreams of Greece, Rome, and European Civilisation at its finest. This is the core appeal of what the Classical has meant to successive generations, and why it continually resurfaces.

While Rome stood, the Classical style, in all its forms, flourished. After the Sack of Rome in 410 AD, a huge gulf of time passed with little art and architecture to match the heights of the ancient world. During the Middle Ages various states and powers wrestled for control in Europe, with many of them modelling themselves as the return of, or a new version of Rome, and art during this period drifted away from classicism and the ideals that it pursued.

The Return of the Classical in the Italian Renaissance, c.1400-1550

At long last, a fascination with the Classical world arose during the Italian Renaissance, c.1400-1550. Artists in Florence, Venice, and Rome, sought to elevate their craft and returned to the ancients for inspiration. Many texts on painting and design looked to Classical examples for rules of proportion and architectural models, and all the while artists were constantly comparing themselves to ancient artists.

As cities became wealthier and more confident in 15th century, the people of Italy saw themselves as going through a Rebirth– a ‘Rinascimento’, in the original Italian (Renaissance is a much later French term). Italians constantly saw themselves as trying to recapture the splendour of centuries gone by, and in the Renaissance they felt they had finally achieved this goal. It was said of artists such as Michelangelo that they had finally matched and even surpassed the ancient masters.

The paradox of the Renaissance is that it was an art movement pulled by two seemingly incompatible forces: in one direction: a very strong Catholic Christian faith, and in the other: the allure and majesty of a Pagan Classical world. The Renaissance masters had to try and harness the best of the Classical style, without losing focus on the Christian message and the sense of humility and lowliness felt by men of faith. Artists aspired to create something majestic: but they had to keep track of who they were meant to worship and idolise, namely God, the Virgin Mary, and Christ.

Piero della Francesca's Baptism of Christ, c.1450, in the National Gallery London. Here we see Classical ideas, such a strong sense of geometry, proportion, and dignity, present in this painting. Classical ideas are used here in service of a humble, subtle, and deeply Christian purpose.

To do so they harnessed all they could in terms of Classical systems of symmetry, proportion, and perfection. They studied ancient sculptures that were discovered.

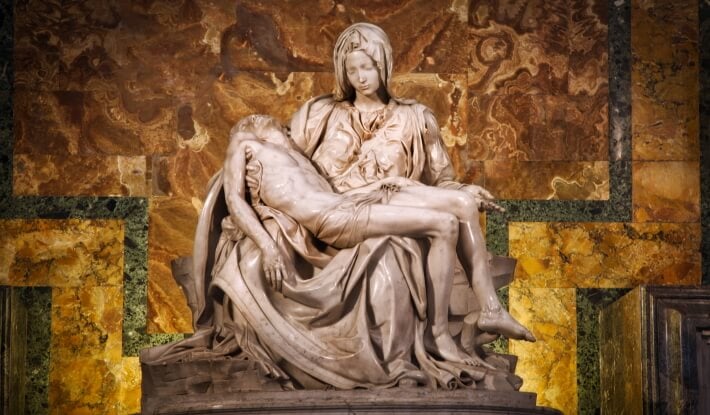

A good example of how the Renaissance artists adapted the Classical style to their own ends is Michelangelo’s Pieta. Here, the Virgin mother holds the deceased Christ across her lap. The body of Christ is drawn from Classical torsos: muscular, athletic, powerful, he appears like a Classical Apollo, the pathos of his death increased by the splendour of his physical form. Mary too is remarkably youthful and beautiful. Anguished and in mourning, her face is nevertheless soft and elegant, yet poised, with a Classical Stoicism, and her feminine figure is evident from the handling of the dress.

Michelangelo's Pieta, c.1499, one of his earliest, and most Classical masterpieces. The exceptional beauty and youthfulness of Mary and the heroic figure of the Apollonic Christ draw heavily upon Classical sculpture from Greece and Rome.

The style of Raphael is probably the most Classical of all the artists of the Italian Renaissance, to such an extent that he took the style to its extreme. He was an artist in huge demand in his short lifetime (1483-1520), and to be able to keep up with the number of projects he had he made use of a large workshop, with dozens of assistants who executed a great deal of paintings we attribute directly to him. They all worked in a singular style, which strove for absolute perfection above all, and total homogeneity.

The Classical style to many does in fact symbolise perfection, art at its zenith. To others, however, it can be hugely stifling, a hindrance to creativity. It is no surprise that after Raphael we see artists rejecting his obsession with perfectionism, attempting to take art in more original, more earnest, and more expressive directions.

Baroque, Mannerist: All art as just variations on the Classical?

Patterns in art history tend to repeat. Just as the original Classical style shifted into Hellenistic, so too did the Renaissance shift into Mannerism and the Baroque, c.1560 – 1750.

The Classical canon, and existing modes and rules of art expanded. Art became more expressive, often more floral, and more sides of humanity were shown besides the dignified heroic godlike faces and figures of the Classical period and the Renaissance.

But there always remained a love of the Classical world, and the perceived prestige, learning, education, and grandeur that comes with it. Some of the masterpieces of the Baroque period, such as Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne, were explicitly taken from Classical poems and texts.

Detail from Bernini's Apollo and Daphne, c.1625. An unrivalled masterpiece of the Baroque. This work is based on a section of Ovid's Metamorphoses, one of the most important and influential poems ever written. While the source is Classical, the depiction is very Baroque: decorative, emotional, more erotic: very similar to the ways the Hellenistic period differed from the Classical.

In the Mannerist movement too, a short lived but important period in the late 16th century, we see artists stretching, quite literally, existing rules of proportion. The Madonna with the Long Neck shows the artist, Parmigianino trying to find new proportions, new ways of displaying female beauty, adapting Classicism to create a new artistic style in itself.

Parmigianino's 'Madonna of the Long Neck', oil-on-panel. c.1535-40. The artist, who tragically died aged only 37, left this work unfinished at the time of his death. In it, he wildly distorted human proportions for his own artistic ends, trying to find an original way of depicting Christ and the Virgin Mary, but still using Classical elements.

The Neoclassical Movement and The Grand Tour c.1760-1900

A wide appreciation of the Classical period came during the period of the Grand Tour, where wealthy aristocratic nobles from Northern Europe went on long trips and voyages to see as much of Rome and neighbouring cities as possible, especially after the discovery of Pompeii in 1748, which revealed original Classical art not seen for some two thousand years.

The rediscovery of ancient sites, and the scholarly reflection that ensued, meant the progression of art was less organic, and more structured and academic. As opposed to artists trying to emulate Classical artists, often without reference to actual art and architecture, and by simply chasing an idea, scholarly study meant that in the 18th and 19th centuries there was more in the way of architecture, decorative arts, and interior design that drew upon the Classical tradition.

Prominent European leaders and monarchs also looked to the classical period to enhance their own image and prestige, such as Louis XVI and Napoleon in France, and Tsars such as Nicholas I in Russia.

Leading artists of the Neoclassical movement include Antonio Canova (1757-1822), Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1884) and Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825). These artists reacted against the frivolous nature of the Rococo, a decorative style lacking serious subject matter, and turned back to Classicism to elevate their art once more.

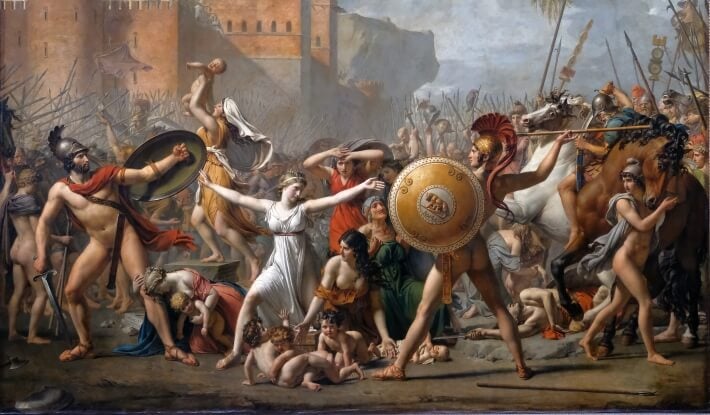

The Intervention of the Sabine Women, by Jacques-Louis David, 1799. David is the most famous painter who worked in the Neoclassical style, and this masterpiece combines a legendary Roman subject with an artistic style trying to be as Classical as possible.

In the world of the decorative arts, furniture pieces and antiques note the shift in and out of Classical and less Classical styles. When the transition in France was made from Louis XV to XVI style, for example, the flamboyant, Baroque excesses of the former were curtailed, and there was return to discipline, with stricter, column-like, tapered forms, imitative of architectural elements, with decorative elements such as friezes like those on Classical buildings.

The Classical and the Contemporary

Historically Classicism has been the predominant style in European art. However, in modern times, abstract and contemporary art have taken over, and artists working in a realistic, naturalistic, and objective style of art are somewhat of a minority.

Nevertheless, there are many artists working to keep the ancient flame alive. Against the onslaught of contemporary abstract art, Classical fine art is somewhat of an antidote. While Picasso’s and Mondrian’s continue to sell for record amounts, the exhibitions on Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, and Caravaggio are the ones that sell out in record time. People still hunger for Classical art and its pursuit of timeless beauty.

See, for example, paintings by the likes of Patricia Watwood, a leading contemporary classical artist. These paintings have a comforting spiritual appeal that abstract art cannot provide, and her fight is one shared by many using traditional methods in their art: to unearth beauty and restore it as art’s true focus.

Not that all art involving the Classical style has to be so serious. Léo Caillard, for example, takes famous artworks and monuments, including those that are scattered across the City of London, and gives them a modern make-over. In doing so, he is making the point that it only takes a slight adjustment to the appearance of Classical works to make us realise that at heart, the legendary figures and towering heroes shown aren’t that far away from us, and that fundamentally we are all people made in the image of Classical masterpieces.

‘To the Friendship between the Classical and the Contemporary,’ Léo Caillard, 2018. The French artist, known for decorating Classical works such as these sculptures at Bush House, London, made this as part of the ‘Classical Now’ exhibition series at King’s College London in 2018, celebrating the continuing links between past and present.

In a profoundly fundamental way, the essence of European culture and civilisation will always be strongly indebted to the Ancient world, and a small group of people in 5th Century B.C. Athens. Our arts will always be infused with the style they created, and the canon of the art they developed.