For the past couple of months, as you walk down historic Mount Street in Mayfair, something colossal is ready to great you, just before you reach the junction with Berkeley Square. Huge boards adorn the changing building, proclaiming “Bacchanalia- coming soon”.

The signage indicates the opening of a new mega-restaurant, Bacchanalia, to rival other giants of the culinary scene in the neighbourhood such as Scotts, 34, Amazonico and Sexy Fish.

Bacchanalia - located just a stone’s throw from Mayfair Gallery - promises a magnificent new central London venue to cater to those hungering for some Classical mystique on their evenings out.

But what lies beyond the grand facade, and might its name ‘Bacchanalia’ give us some clues as to what we can expect?

Read on to find out more about the ancient origins of Bacchanalia, how they captured the imagination of artists and revellers over the centuries, and what you should keep an eye out for should you choose to attend a night of Bacchic revelry in Mayfair.

What are, or were, Bacchanalia?

Bacchanalia were large private feasts and parties put on by the wealthy Roman elite from about 200 BC onwards, in Ancient Rome, and in rich private estates in the South of Italy. They were held, nominally, in honour of Bacchus, the god of wine, and featured exotic menus, copious amounts of food and drink, and various forms of live entertainment. They were the ancient equivalent of parties for high society, exclusive events held out of the public eye, where invitations were made on a strict and highly exclusive basis.

These parties, furthermore, had a strong religious and cultic aspect, drawing heavily on existing Greek traditions of festivals and parties, which were held in honour of the Greek equivalent of Bacchus: Dionysus. But whereas these Greek festivals were public, open to all, and largely free to attend, the Roman Bacchanalia were exclusive, mysterious events, shrouded in secrecy, where only whispers of what went on were shared – everyone else left guessing as to the nature of Bacchanalia’s strange and decadent feasts and rituals...

What happened at these parties? Why were they regarded with such envy and suspicion by those who didn’t attend? And who exactly was the god Bacchus, in whose name these parties were held? What did his cult even involve, and consequently, what you should expect from a night at Mayfair’s new shrine to this ancient deity? Read on to find out.

As we shall see, there is a fine line between fine dining and the scandalous mystique of the rites of Bacchus. Follow along, but be warned: tread carefully!

The Origins of Bacchanalia – The God Dionysus

Bacchus, or Dionysus, to use his Greek name, was an ancient god and one of the twelve most important deities who formed the Olympic Pantheon. He was worshipped as far back as around 1500 BC: effectively from the dawn of the Greek world.

Unlike other gods, worship of Dionysus didn’t exactly consist of temples and shrines and ordinary prayer. He represented wine and relaxation, a break from year long toil in the fields, and as such he became the patron god of many ancient festivals.

The highlight of the Greek calendar was the City Dionysia, held in Ancient Athens. It consisted of a series of huge festivals and feasts that were held over multiple weeks, with various forms of publicly funded live entertainment. The Greek plays and tragedies, legendary pieces of literature and drama that are still enjoyed today, were all performed at festivals in honour of Dionysus. These festivals were an early form of what would later be adopted by the Romans and evolve into Bacchanalia.

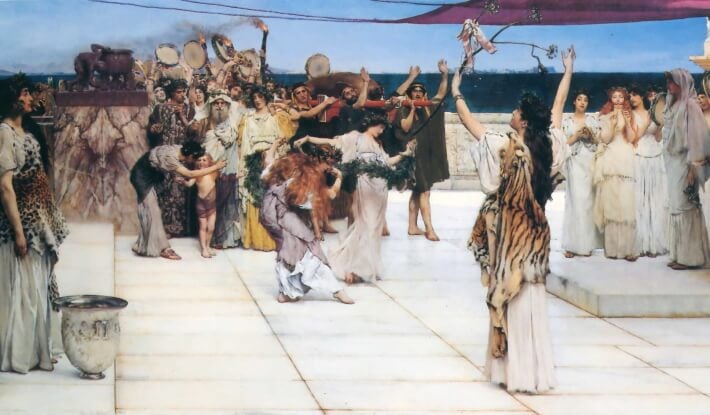

An artist’s impression of how the City Dionysia might have looked: ‘A Dedication to Dionysus’, by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1889. Alma-Tadema is known for his spectacular paintings that evoke the luxury, sensuality, and decadence of the ancient world. In this work he attempts to recreate the feel of ancient Bacchic ritual.

While these great public, open events were held in Dionysus’ honour, various secretive religious centres and cults were established in his name. Known as ‘mysteries’, their exact origins and practices were shrouded in secrecy. Dionysus, it seemed, had a dual nature. Publicly, he was the god of parties and festivities, but in secret, he was a powerful, sinister, strange force of nature, worshipped because he represented something more primal, carnal, and animalistic about human nature.

Bacchus in the Ancient Greek imagination

Bacchus is best known as the God of wine, and this was in fact his main attribute. But like all ancient gods and goddesses, what he represented was far more complex, and he personified a far deeper and more profound aspect of the ancient Greek psyche – or soul.

Despite being an established god in Greek thought, Dionysus (or Bacchus) had always been seen as an outsider – often considered an Eastern and imported deity. A charismatic, mysterious, profoundly powerful but uncontrollable force of nature, it took a very long time for the Greeks to come to terms with exactly what he meant, and how to go about worshipping him.

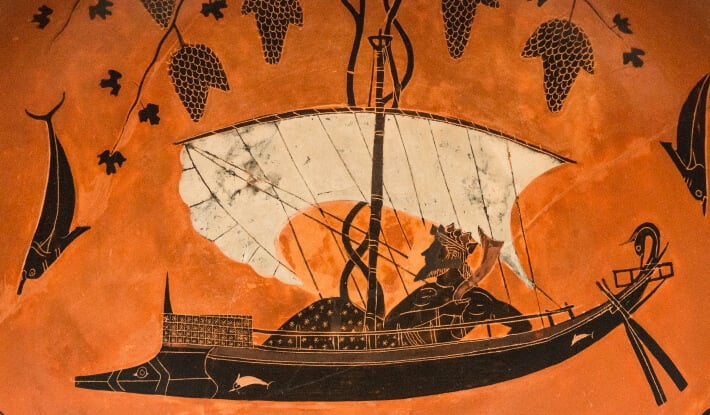

One of the oldest images of Dionysus, or Bacchus. By the great Greek Vase painter Exekias, c.520BC, this beautiful painting shows the god reclining lazily on a small boat: having been captured by pirates, he demonstrates his divinity by making the mast sprout vines of grapes, and turning the pirates into dolphins, which leap around the boat as he sails on.

First of all, it’s safe to say that the Greeks liked their wine! The sea, in the poems of Homer, is called ‘the wine-dark sea,’ and libations - offerings of wine poured out for the gods - are as old as Greece itself. (Island restaurants today will serve you the best €6 litre of wine you’ll ever have! Not that they’ll be much of that at Mayfair’s Bacchanalia!)

I digress. The point is: wine was an important part of life, and there had to be a god to go with it, one equally as important. But wine stood for more than just a nice drink, and Dionysus represented more than just getting somewhat inebriated and enjoying some good food. Dionysus represented a dangerous force of nature, both a peaceful and dangerous force: that strange phenomenon of losing control of oneself but being introduced to a new world of experience and vision: treading the line between relaxation, and intoxication.

Dionysus gave freedom, offered comfort, and could grant worshippers a divine state of pleasure and ecstasy. But as with all gods, what he gave he could also take away. He could inspire madness, maenadic fits of possession and fury, acts of bestial violence, and reduce worshippers to animals and inflict wicked acts of cruelty against those who offended him.

Euripides’ Bacchae – a Bacchic party to avoid!

These aspects of the God are best articulated and explored in that Ancient Greek masterpiece of drama, Euripides’ Bacchae, originally performed in the Theatre of Dionysus in 405 BC. In this play, the god Dionysus comes to the city of Thebes with dire results.

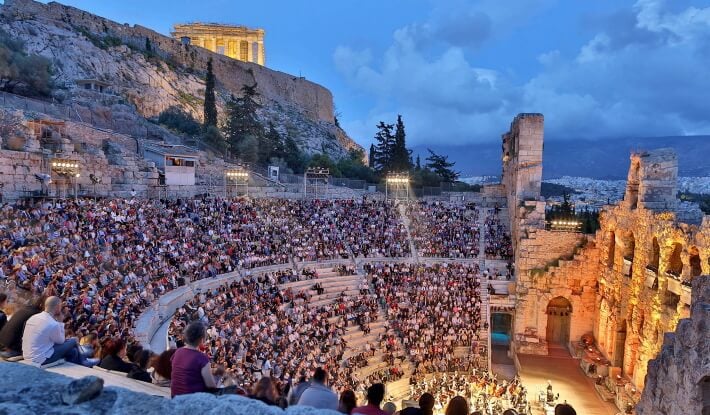

Not the Theatre of Dionysus! (the original venue for all the great Greek plays and tragedies) but the Roman Odeon of Herodes Atticus, a later building, built under the glow of the Parthenon, as it might have looked in the City Dionysia, the cultural highlight of the Ancient Greek world.

He begins by recounting the story of his birth. Born to the Theban woman Semele, and fathered by Zeus, the women of Thebes deny Dionysus’ origins, and say that the story with Zeus is a lie to cover up the fact Semele fell pregnant to some mortal man. Dionysus drives the women of Thebes mad in revenge for denying his divinity, and calling his mother a liar, and sends them out into the mountains to live like savages.

Dionysus then comes to the palace, in the disguise of a priest of his own cult, and is promptly arrested by Pentheus, prince of Thebes. Pentheus, however, is both disgusted and intrigued by the rites of Dionysus, and despite denying Dionysus’ divinity and in particular his Greek divinity – considering him some barbaric Easterner - he can’t help but want to know more about this mysterious force of nature.

Dionysus subsequently breaks out of his chains and causes a huge earthquake and fire to ruin the palace, revealing more and more of his divinity and power as the play progresses. As he does so, he plays on Pentheus’ curiosity, eventually driving him mad, dressing him up as a Bacchic maenad with fawn skins and a thrush, and leads him to where the women of Thebes – including his mother – are located, possessed by Dionysus’ power.

Pentheus’ act of submission fails to appease Dionysus, however, and he commands his followers, the maenads, to kill Pentheus: and they do so, tearing him limb from limb. Dionysus’ dangerous, capricious, and proud character is shown. The point is made: you deny – and accept – Bacchus at your own peril.

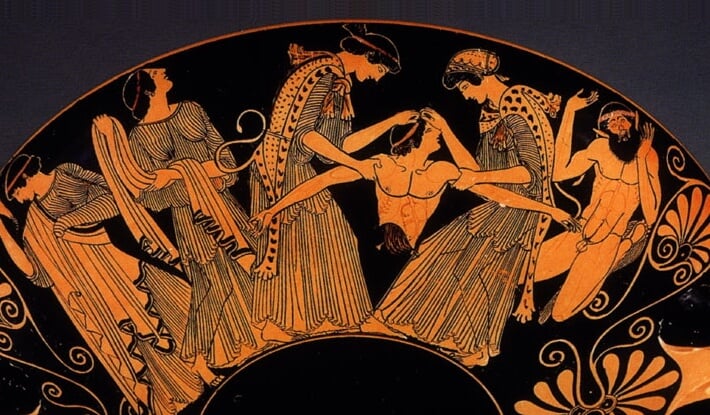

An ancient Greek vase painting showing the climax of the play. Pentheus is torn apart by his mother and aunts, in an act of furious possession brought on by Dionysus. The Death of Pentheus, c.480BC, on a Red-Figure kylix krater by Douris.

As to how this says something about human nature – as all great literature, especially Greek literature does – is that the Bacchic urge, the need to follow Dionysus is always there. His power is real, and to suppress it and deny it, to deny that bestial, animalistic, impulsive aspect of one’s character is dangerous folly. Equally dangerous, however, is to think that this part of human nature can be explained rationally, that Dionysus can be tamed.

In other words: don’t deny that you really want to make that reservation, but if you do, don’t have too much fun!

Bacchanalia in Ancient Rome

As the power of Greece faded, Rome rose to the prominence, becoming the cultural heart of the Mediterranean in the process, c.200-150BC. As it did so, it adopted many of Greece’s cultural traditions, including the worship of Bacchus.

Bacchanalia were the Roman equivalent of the Greek parties and festivals we have seen above. They combined aspects of the Ancient Greek Symposium and the City Dionysia, with a more laid-back, party atmosphere.

Unlike the Greek Dionysia, Bacchanalia were smaller-scale, private events, hosted and paid for by Rome’s wealthy elites. Just as the Greeks adopted Dionysus from the near-Eastern world, so too did the Romans adopt Bacchus from the Greeks.

These parties were initially women-only events, held in Southern Italy, around 200BC. Over time, men began to attend, however these clandestine cults and parties were regarded with such suspicion and hostility, and they became so popular, that the Senate took measures to curtail them. The main source about Bacchanalia around this time is Livy, a deeply socially conservative thinker and historian, who considered these orgiastic festivals hotbeds of debauchery, degeneracy, and treasonous scheming against the state – not without good reason.

Despite efforts to curtail them, Bacchanalia survived well into the time of the emperors, with rather scandalous results. The emperor Caligula would hold feasts - supposedly celebrating Bacchus - at which he would force married couples to attend in order to take his favourite married women somewhere more private before returning to share the sordid details in everyone’s presence.

A Roman Orgy by Henryk Siemiradzki, c.1880. Nineteenth century paintings generally fail to do justice to just how raucous and indulgent a proper Roman Bacchic party could be.

The most famous examples, however, are the orgiastic, drunken, drug-fuelled parties hosted by the emperor Nero. Known for playing the fiddle while Rome burned, what’s less well-known is that he used the land cleared by the fire to build the so-called ‘Domus Aurea’ – his sex palace.

Beneath a hundred-foot-tall statue of himself, he would host feasts where people stuffed themselves until they vomited, then proceeded to engage in drunken orgies until they collapsed from exhaustion – often with a sham wedding thrown in where he would ‘wed’ his favourite slave-boy, and ‘consummate’ the marriage promptly after.

No wonder, then, that Thomas Couture’s painting at the top of this article is titled ‘The Romans in their Decadence.’ Many of these stories come to us in the writings of later historians, and because of the secrecy around these events, it is no wonder that fantastical tales were written about what went on, with most believing that ‘worship of Bacchus’ was just a façade, used to justify acts of the utmost debauchery and degeneracy.

Bacchanalia in Art after Ancient Rome

These crazy, drunken parties and orgy filled evenings came to an end with the fall of Rome – many considered that Rome fell from the inside, due to being such a hotbed of decadence and moral decay. Nevertheless, Bacchus remained a hugely popular figure, particularly in the art of many periods and styles after the fall of the ancient world.

Multiple Italian Renaissance artists and sculptors, including Michelangelo, depicted Bacchus (as shown below left), but it is often in later, more flamboyant, more indulgent art styles that Bacchus came ever more to the fore.

Bacchus was a popular subject for the late Renaissance artist Titian, who enjoyed painting both sides of the god’s personality, but he appears even more famously in the art of Caravaggio, that charismatic personality of the Italian Baroque, known for living a life both sacred and profane.

A famous painting of Bacchus by Caravaggio, which hangs in the Uffizi (shown below right), depicts the god in a highly sensual and provocative fashion. It was commissioned by the wealthy Cardinal Del Monte, who was a fan of classical Greek mythology, and who used images such as these to demonstrate his knowledge of art, music, and theatre.

Left: Michelangelo’s Bacchus invites you for a drink, although he looks like he’s had one too many himself! Right: Bacchus, by Caravaggio, the Baroque painter par-excellence.

An artist inspired by Caravaggio was the Spanish painter, Diego Velázquez. Caravaggio had a habit of painting Biblical scenes with the characters depicted in contemporary clothes and dress, as if Christ could appear in a Roman tavern, like he does in The Calling of St Matthew.

Following Caravaggio, Velasquez did this in the case of Bacchus: depicting him surrounded by Spanish labourers, thus presenting him as a champion of the working man, and the liberator of the people from the monotony and slavery of daily toil.

The painting, titled 'The Triumph of Bacchus', and shown below, presents a more down to earth depiction of Bacchus, bringing the world of Classical pleasure and festivity a little closer to everyone.

‘The Triumph of Bacchus,’ by Diego Velázquez (1599-1660), Museo del Prado, Madrid

Bacchus, and Bacchanalia more generally, also provided a popular subject matter for artists during the Rococo and Neoclassical periods.

Fine sculptures - such as those by Clodion - depicted the god surrounded by nymphs and satyrs, and worshippers in the throngs of ecstasy and sensual pleasure. Bacchus was a popular subject for this leading artist, and fine terracotta sculptures, such as the one below right, show Bacchus tantalising a nymph who clings off him, lusting after him and his fruit.

In our collection at Mayfair Gallery we are particularly pleased to have a sculpture titled 'Bacchanalia' by the Dutch artist Paul Brou. This large and wonderfully carved sculptural group depicts a young and drunken Silenus as he carouses with his merry band of Bacchic revellers.

Comparing these two works we can see both sides of the god Bacchus: the playful, merry, and lighthearted side of Bacchus and his affinity for nature, contrasted with the sensual, physical, powerful and erotic sway of Bacchus and of his female followers, the maenads.

Left: 'Bacchanalia' by Paul Brou (Dutch, 19th Century), Mayfair Gallery, London. Right: ‘Bacchus and a Nymph with a Child and Grapes’ by Clodion (French, c.1800), Metropolitan Museum, New York.

So what can we expect from Mayfair's latest restaurant: Bacchanalia?

No doubt Bacchanalia aims to draw upon the mystery, wonder, and promise of sensual stimulation and delight that Classical ideas of Bacchic parties conjure up. Alongside this, it promises to be a gateway to a world of culinary delights, inspired by the cuisine, culture, and history of the Mediterranean, and all its ancient splendour.

The decoration, featuring magnificent Classically inspired statutes by Damien Hirst, and an underground level designed to appear like the Greek underworld has an indulgent Baroque magnificence – clearly intending to marry promises of Bacchic pleasure and sensuality with a real Classical grandeur and majesty.

All in all, Bacchanalia promises to be more of a sophisticated venue inspired by all of Greece and the Mediterranean, rather than a specific aspect of Bacchic cult, or an attempt to recreate Caligula and Nero’s orgiastic parties – though Bacchanalia is definitely appealing to that temptation!

Just as Greek tragedy was a lens through which to enjoy every myth and aspect of the Greek world (not just those relating to Dionysus), so too does Bacchanalia promise to be a lens to enjoy all aspects of the Classical world, through the lens of unmatchable Bacchic pleasure.

Based on the rich artistic legacy and wealth of ancient inspiration we have explored, we can expect Bacchanalia to be a place overflowing with indulgent sensory experience, and pure, sensual delight and pleasure - a place to indulge culinary and carnal desires, and enjoy an evening truly in the spirit of the ancient god of relaxation, escapism, and decadence.