As one of the seven metals of antiquity, silver has been an important material to humankind for millennia, prized by civilizations in every corner of the globe.

Throughout history, silver has been used for a range of practical and decorative purposes: it has been used as money, and yet also as a material from which to craft jewellery, hollow- and flatware, objects and even whole pieces of furniture.

Over time, silver items have been crafted in a variety of styles to suit contemporary needs and tastes. Additionally, the production of silver objects has undergone major changes, particularly following the understanding of how to alloy silver with other metals in the medieval period, and the rise of industry in the 18th and 19th Centuries.

This blog will explore the evolution of the use of silver from antiquity to the modern day. However, in order to understand why silver was used in certain ways and how its use has evolved, it is first necessary to understand the unique properties of the prized material.

What are the Properties of Silver?

Silver’s properties and qualities determine not only what it fundamentally is, but also what it can be used for as a material. Ultimately it is these properties that give silver its unique appeal and in turn its association with value, luxury, beauty and grandeur.

Shiny, white appearance

Silver is valued for its brilliant white metallic shine. It is, in fact, the most reflective of all metals. Interestingly, the word ‘silver’ derives from the Latin argentum, which has its roots in the Proto-Indo-European word for ‘shiny’ and ‘white’.

The appearance of silver is so distinctive that the use of the word ‘silver’ in the English language defines both the metal itself and its unique colour.

Silver’s white, lustrous appearance makes it an appealing metal to use in the decorative arts. Silver has, for instance, been used in the production of mirrors for centuries. It is often both applied to the glass to provide a reflective surface, and used to craft the mirror frame.

Non-reactivity

Silver is notable for its non-reactivity. It is characterised as a ‘noble metal’, and grouped with other metals, including ruthenium, rhodium, palladium, osmium, iridium, platinum, and gold.

Along with the other noble metals, silver resists corrosion and oxidisation in the air. This makes it perfect for crafting items that are built to last even if they are regularly handled and used, since they will not wear down or tarnish.

Malleable, ductile

In its pure state, silver is very soft. This makes it malleable and ductile, meaning it can be crafted into form quite easily, through a process of working and annealing.

Sheets of silver are hammered into shape when cold, and annealed – that is, it is warmed to soften it, making the silver more pliable. Working this way, silver can be used to create a range of holloware, flatware, cutlery and jewellery.

Electrical and thermal conductivity

Silver has the highest electrical and thermal conductivity of all the metals. While this may seem an unimportant fact, these properties make silver the perfect metal to use in electrical devices. For these qualities, silver is highly sought after in the modern world.

Aseptic, antibacterial

The fact that silver is both aseptic and antibacterial make it the perfect metal to use to create sterilised objects or environments. For this reason, silver can be seen to have health benefits.

It is therefore unsurprising that silver has been used extensively to produce utensils for eating and drinking, and is used in the modern world to help prevent disease and in areas such as water purification.

History of Silver

It is owing to its unique properties that silver has been able to perform a variety of important functions over time, which we will now explore through a brief history of silver and silverware.

Silver in Ancient Times (7th Century BC - 5th Century AD)

Silver has been mined and crafted into objects for many millennia. In the ancient period, it was used for a variety of purposes, from making precious jewellery to fine hollow- and flatware. However, silver was primarily used as a form of currency.

Silver as coinage

Silver and gold coins have been in circulation since the ancient times. Of the two, it is believed that silver is the oldest mass-produced form of coinage. Indeed, the ancient Greeks regularly used silver staters, drachmas and obols to trade within the Mediterranean world.

Greek silver stater coin, c.350 B.C. Posted to Flickr by Dorieo. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

Money and silver are intricately bound together. This is indicated by the fact that, in many languages, the word for silver is also the word for money. The French word ‘argent’, for instance, has this double meaning.

Silver lends itself to being used as a form of currency because it is rare enough to be considered precious, but no so rare that it only exists in trace quantities (as with some of the other noble metals).

And most importantly it is non-reactive. This means that despite being handled on a day-to-day basis, silver coins will not rust or corrode over time.

Silver also has a relatively low melting point, which means it can be easily melted down into coins.

For these reasons silver is ideally suited to being used as a 'storer of value', or as money that can be used to trade.

In its history, silver and money are intimately connected. It is partly for this reason that silver has associations with wealth and affluence today.

Decorative arts & burial objects

Its compelling appearance combined with its role as a 'storer of value' made silver an ideal material in which to craft luxury goods.

In ancient times, silver — in its pure form — was much harder to come by than other precious metals, such as gold. For this reason, it was considered extremely precious and used sparingly to create jewellery and small objects, often devotional in character.

Because silver was obscure and mysterious, as well as white and lustrous, it was compared with the moon, called ‘Luna’ by alchemists and associated with the goddess Diana.

Excavations in several countries have uncovered ancient graves, which are filled with silver items. These individuals were of a high-status, and the items they chose to accompany them to the afterlife had to be their most precious. The presence of silver in these graves indicates that silver was incredibly valuable in the eyes of the ancients.

The silver bowls, dishes, cups, and more, would have been buried so that they would be presented as a gift to the gods in return for safe passage to the afterlife. As a noble metal, silver would not corrode over time, making it the perfect offering.

The presence of silver items in important burial sites indicates the value it held for ancient civilisations.

Silver in the Medieval Period (5th Century - 15th Century)

Throughout the Middle Ages, silver continued to be used to make precious decorative objects. It was used to make jewellery, for domestic decoration, to embellish armour, and as a thread that could be woven into tapestries.

Furthermore, with the rise of the Church in the 11th Century, silver was increasingly used to produce reliquaries and liturgical objects, such as crucifixes and chalices. Its purity and lustre made silver an ideal metal to craft devotional objects with.

German silver, silver-gilt, niello, and gemstone chalice and paten, 1230-50. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

Sterling silver & silver alloys

While the softness of silver has its benefits, it also sets limitations on what can be made from it. To solve this problem, medieval craftsmen began to combine (or 'alloy') silver with other metals, such as copper, to increase its hardness and strength.

Sterling silver — an alloy that is approximately 92.5% silver and 7.5% copper by weight — first appeared around the 12th Century. This new form of silver was much stronger and more versatile, and could be used to create new types of objects.

(Note again the intrinsic link between silver and money: ‘Pound Sterling’, the modern-day currency of the United Kingdom, literally derives from the measurement of one pound of sterling silver.)

Discovery of the New World (mid-15th Century)

The traditional sources of silver in Europe — such as Goslar in Germany — were augmented, in the second half of the 15th Century, by the European discovery of the New World. Its natural sources of silver were significant and were quickly plundered by Spanish conquistadors and transported across the globe to be sold.

Following this conquest, Central and South America — particularly around the areas we now know as Peru, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina — became the chief suppliers of silver. These countries, with the addtion of Mexico, continue to be in the top 7 silver-producing nations worldwide.

Interestingly, the name ‘Argentina’ derives from argentum, which, as we know, is Latin for silver.

The High Point of Silversmithing (16th Century-18th Century)

The discovery of new sources of silver in the New World, and its subsequent export across the globe, prompted the emergence of a new generation of silversmiths.

To begin with, silver continued to be used sparingly to craft jewellery and small religious objects, as it was in the Middle Ages. It was also often applied to, or inlaid in, decorative objects.

Over the course of this period, however, the demand for grand silver items increased. This was partly spurred on by increasing levels of expendable wealth, and the desire to use material possessions to reflect status.

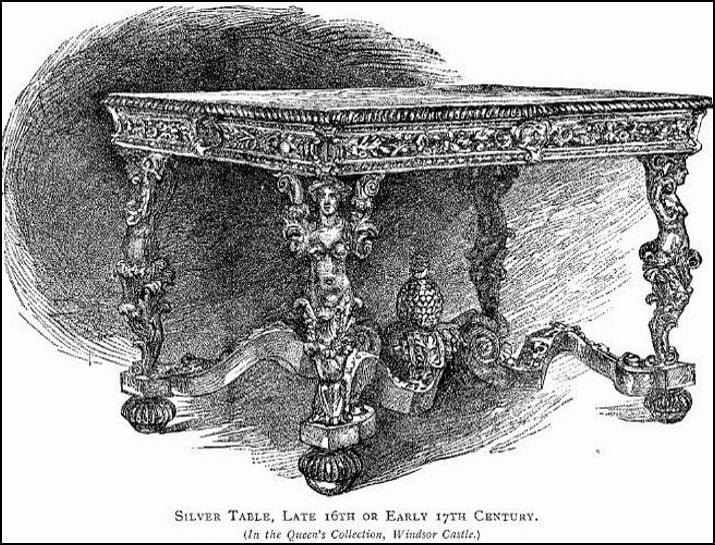

The below Baroque style silver table, now housed in the Queen’s Collection at Windsor, is a dazzling example of the most extravagant of silver items being produced in this period.

‘Silver table, late 16th or early 17th Century’, from Illustrated History of Furniture, From the Earliest to the Present Time from 1893 by Litchfield, Frederick, (1850-1930), Accessed via Wikimedia Commons. The silver table is held by the the Royal Collection Trust and has been attributed to Andrew Moore (1640-1706), working to a design by Daniel Marot (1661-1742).

The vogue for luxurious silver furnishings properly took off in Europe in the mid-17th Century, inspired by the French court of Louis XIV.

Following Louis XIV’s example, European monarchs began to commission silver tables, stands, mirrors, commodes, benches, candelabra, vases, statues, chandeliers, and more.

These attempted to emulate, and compete with Louis XIV’s solid silver furniture at Versailles, made by the craftsmen of the Manufacture des Gobelins and the Galeries du Louvres.

However, few late 17th and early 18th Century French items of silver furniture survive. This is because Louis XIV and Louis XV both issued several edicts that demanded large pieces of silver be melted down, literally 'liquidated', to cover the costs of various fiscal crises.

Several grand silver pieces in the English Royal collection were similarly melted down. Fortunately, silver tableware was spared this fate, owing to the small scale of cutlery, plates, jugs, and other pieces of serveware.

Important makers

The 18th Century saw the emergence of some of the most important silversmiths of all time. These included Paul de Lamerie, the Garrards silvermiths, the Bateman Family, Paul Storr and Paul Revere.

Paul de Lamerie (Dutch, 1688-1751) — the appointed silversmith to King George I of England — was famous for his ornate, Rococo style silverware. These items were decorated with engraved, relief and applied designs, taking the form of floral swags, cartouches, sea monsters, and more.

The Queen Adelaide Garniture de Table, 1796, by Garrards silversmiths.

The Garrards silversmiths (English, founded 1722) worked in a similar style, creating opulent royal pieces, such as The Queen Adelaide Garniture de Table, shown above. This piece was gifted by Queen Adelaide (wife of King William IV of England) to the first Earl Howe, Richard William Penn Curzon, in 1796.

In the late 18th Century in Europe, the taste for refined, Neoclassical style silver items developed, partly as a reaction against the opulence of the Rococo.

The Bateman Family (English, c.1773), Hester Bateman in particular, crafted elegant silver pieces of tableware which sparingly employed Neoclassical motifs, such as fine beading and bright-cut engraved decoration.

Collection of late 18th century Neoclassical style silver objects comprising a teapot (by Peter and Ann Bateman), a hot water urn, a creamer, and a hot water jug (all by Hester Bateman). The Birmingham Museum of Art. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

Paul Storr (1771-1844) is another celebrated English silversmith who worked in the fashionable, Neoclassical style, crafting grand pieces of tableware for the English nobility and King George IV.

This movement away from the Rococo to the Neoclassical is further illustrated in the work of the patriot silversmith, Paul Revere (American, 1734-1818). Before the Revolutionary War, Revere was generally working in the Rococo style, while after it, he began to create more refined, Neoclassical silver pieces.

Silver tableware

As demonstrated in the examples above, silver was primarily used to craft fine objects of tableware.

The fashion for silver tableware emerged together with the taste for fine dining. Elaborate dining practices became popular among the French elite in the late 17th and 18th Centuries, and were soon picked up elsewhere in Europe.

Mealtimes were ceremonious occasions, which often consisted of several courses of food, beautifully presented on fine pieces of silver. The abundance of silver — plates of varying sizes, cutlery, sauceboats, salvers, centerpieces, and candelabra — was an elaborate and magnificent display of status and wealth, intended to impress dinner party guests.

With the discovery of the New World, new foodstuffs began to be imported into European countries. New forms of silverware were thus created to serve these new foods, such as the coffee and tea pot.

French Neoclassical style silver candelabrum (one of a pair), by Robert Joseph Auguste. The Metropolitan Museum, New York. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons. French Rococo style silver cofeepot, by François Thomas Germain, 1757. Decorated with coffee leaves and berries on the spout and base of handle, playfully referencing its function. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

Silver’s age-old association with status made it well suited to the production of fine tableware. It is also anti-bacterial and hygienic, and therefore perfect for use in dining.

Silver cups and trophies

In America from the late 18th and early 19th Century onwards, silver was increasingly used to make presentation vessels, which were used to celebrate civic and political victories. These grand pieces often took the form of classical urns or chalices.

This relates to the earlier practice in America of awarding the winners of sporting events with a silver cup. These chalices were often Neoclassical in style, since the act of presenting winners with a prize originated in ancient Greece.

American Neoclassical style silver presentation vase, 1825, by Sidney Gardiner and Thomas Fletcher. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

One of the earliest examples of these silver twin-handled silver chalices is the Kyp Cup, which was crafted by Jesse Kyp, and presented to the winner of a horse race in New England in c.1699. The Stanley Cup, Americas Cup and World Cup are well-known silver trophies that have descended from this early prototype.

To this day, silverware continues to be a marker of success within the sporting world.

The chalice’s form, with its associations of success, combined with the costliness and bright, shining appearance of silver, make a silver cup a highly desirable prize.

The Rise of Industry (mid-18th Century-19th Century)

In the periods discussed up to this point, silver was the exclusive preserve of the social elite. This is largely because silver was a costly raw material, but also because it was expensive to commission trained silversmiths to handcraft items.

Silversmiths, before the rise of industry, would hand-work sheets of silver, using hammers and other tools, occasionally annealing (heating to soften) it, and gradually raising it into shape. This is how bowls, plates, jugs and other such items were crafted. The bits of an object that couldn't be constructed this way — such as candlestick stems, tea spouts, or the bracket feet of salvers — were cast separately. These seperate parts were then combined by soldering and riveting. This process was time-consuming and required highly-skilled labour.

With the rise of technology in the mid-18th Century, however, machines were invented that could produce silver goods quickly and cost-efficiently, requiring only a semi-skilled workforce to oversee the process.

The silver objects that were created this way could be sold at a much cheaper price than ever before. For the first time, silver items could be purchased by the middle classes, and not just the gentry and aristocracy.

Silver plating

The Industrial Revolution brought about huge changes across society, and none more so than in the production of silver items.

One of the most radical of these changes was the invention of the silver plating process, whereby a thin layer of silver could be applied to the surface a cheaper metal. This allowed objects to be created with the appearance of silver, but at a significantly lower cost.

Sheffield Plate — produced in Sheffield between 1760-1840 — was the earliest form of silver plating.

The plating method involves thin sheets of silver being fused (using heat) to a base metal, which, for Sheffield Plate, was copper. Using this layering technique, companies were able to create a wide range of 'silvered' household items, that could be sold to the growing middle classes.

The stamping machine

The Sheffield cutlery industry was even more pioneering in that they were one of the first companies to make full use of stamping machinery. This technology emerged around the same time as silver plating and was equally as revolutionary in its impact on the production of silver goods.

Invented by Matthew Boulton and James Watt, this machine could quickly and efficiently stamp out whole objects. This technique partly fuelled the 19th-century fashion for elaborately-shaped flatware made from thin sheets of silver.

The Birmingham smallware industry — that is, the companies concerned with items like buckles, badges and buttons — similarly began using machines to stamp out forms, reducing the time, effort and cost involved in the production of silver goods.

In this process of rapid industrialisation, however, the stamping machine was soon superseeded by steam power and electricity.

Electroplating and electroforming

After c.1840, the Sheffield Plate method of silver plating was replaced with electroplating techniques, whereby silver is fused to a metal (often nickel, a cheaper alternative to copper), using electricity rather than heat.

Pure silver, rather than sterling (as with Sheffield Plate), tended to be used in this process, but it was very thinly deposited and was susceptible to wear over time. This method produced even more affordable silver wares than Sheffield Plate.

The first electroplating process was patented by George Elkington, who, began in 1841 with one factory in Newhall St. in the Jewellery Quarter in Birmingham, and, by 1880, employed 1,000 people and had 6 other factories.

Elkington produced a wide range of silver objects, from jewellery to plates and cutlery. Companies such as Christofle et Cie of Paris and Tiffany & Co of New York also employed this electroplating method, along with electroforming, which used the plating process to create whole objects.

English silver, parcel gilt salver, electrotype after Russian, St Petersburg original, 19th Century, by Elkington & Co. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

In general, the age of industry saw many traditional hand-crafting methods replaced by machine production. The power-driven lathe, for example, was introduced to spin and polish silver items mechanically, eliminating the need for skilled labour, which demanded time, effort and money.

Late 19th-Early 20th Century

In a reaction against industrialisation, the Arts and Crafts movement deliberately created silver works with a planished surface — that is, the objects exhibited the marks left by the silversmith’s hammer.

The Arts and Crafts school believed in the integrity and value of hand-wrought products, above machine-made ones. The silverware produced collaboratively by Omar Ramsden and Alwyn Carr exemplifies this approach to design.

Silver Arts & Crafts style porringer, c.1925, by Charles Robert Ashbee for the Guild of Handicraft. The Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt in Germany. Accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

Art Nouveau emerged in the late 19th Century, alongside the Arts and Crafts movement. Silver wares in this style emphasised feminine, flowing lines and organic, asymmetrical forms, making great use of relief decoration. Following on from Art Nouveau was Art Deco, with its sharp, geometric forms.

Silver in the 20th and 21st Century

Its unique characteristics mean that silver can be used in diverse ways, and not just as a decorative material.

Today, silver is used in healthcare and medicine, since silver irons and compounds kill bacteria, fungi and algae. Silver is also key to technological advance: over 30% of silver produced in the contemporary world is used in the photographic industry, often in the form of silver nitrate.

Furthermore, almost all electronic devices — in particular, the on/off button part of televisions, lights etc. — is made using silver components. Silver is also used to purify water, and in green technology. Even NASA’s Magellan spacecraft was fitted with silver-coated quartz tiles to reduce solar radiation during a mission into space.

Silver is still valued, however, as a luxury material that can create decorative pieces, such as fine holloware or jewellery. To craft such items by hand, however, requires great skill and patience.

There are, and will always be, pieces that are made to imitate silver, which have been produced en-masse and can be sold cheaply.

It is owing to organisations, like The Goldsmiths Company and Contemporary British Silversmiths, that the silversmith’s art is kept alive. Today, metalworkers, such as Jessica Jue, Nan Nan Liu, Tamar de Vries Winter and many more, continue to produce silver wares that engage with, challenge and redefine the history of their craft.