Few materials or gemstones carry quite the same appeal as this ever popular and highly prized natural mineral. Possessing a richness and vibrancy that is unmatched, malachite is the instantly recognisable, beautiful, deep rich-green gemstone that adorns so many prize antiques.

But why is this: who was it that made it so popular, and how did the use of malachite as a luxury material evolve since antiquity? This is our guide to this timelessly regal material.

What is Malachite?

Malachite is a beautiful and rare natural mineral that has been used for a vast variety of decorative, artistic, and cultural purposes throughout human history. A form of copper carbonate (chemical formula Cu2CO3(OH)2 for the swots!), it is found in caverns deep underground, often above large copper ore deposits, where the conditions are right for it to form as clusters and stalactites, or on very rare occasions, as large masses and crystals.

Its rich green colour and the patterns when cut through is what gives it its name, from the Greek moloche, a variant of the term for the mallow-plant, the leaves of which are similar to the bands and patterns in malachite minerals. It ranks between 3.5 and 4 on the Moh’s scale, meaning it is fairly soft, and somewhat brittle, thus it is most commonly used as a veneer rather than a major structural material, and is often protected beneath layers of wax to prevent damage.

A slice through a beautiful cluster of malachite, showing the rings that indicate the sample's age.

Many of the oldest sources of malachite have since been depleted, and today, while rare, it is most commonly found in Africa, Australia, and the United States, in the state of Arizona in particular.

In Namibia, for example, malachite is found in extraordinarily large crystals. Another location where malachite has historically been mined is Russia, in the Ural Mountains, where it has been found in vast quantities, sometimes as large as 50 tons at a time.

Discovery and Early History of malachite, 4000 B.C. – 600 B.C.

Malachite, due to both its natural beauty and the locations of deposits in the Middle East, has been mined since prehistory, and since the dawn of civilization. It is a mineral that usually forms above copper deposits, and alongside other minerals such as azurite and calcite in caverns and caves, deep underground.

It is most commonly found in the form of stalactites and clusters, but on rarer occasions it can form as immense crystals and magnificent large masses, that can be hewn and cut from the rock in large pieces and slices.

Archaeological evidence shows that it has been mined in the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt and around the Isthmus of Suez as far back as 4000 B.C. and was mined in the Timna Valley in Israel for approximately 3,000 years in antiquity.

In Britain too it was mined at the Great Orme Mines in North Wales, around 2000 - 600 BC. Many of these early mines used naturally occurring malachite to smelt copper; however, since copper is far more readily available from other sources, malachite has been saved and used largely as an ornamental and decorative gemstone since, allowing generations of people since antiquity to appreciate its natural splendour.

It has also been used to make green pigment in paint right up until the Industrial Revolution. Only recently has it been replaced by artificially synthesised copper carbonates to create the green pigment in modern paints.

The Great Ormes Mines North Wales, where c.1800 tonnes was mined for copper smelting in prehistoric Britain.

Malachite in the ancient world: Egypt, Mexico, Greece, and Rome, c.3000B.C – 600A.D

In Ancient Egypt malachite was believed to protect against evil. Its rich green colour gave it huge symbolic importance, and it was believed to represent fertility and new life, with the eternal paradise in the afterlife itself known as the Fields of Malachite.

Despite this, the Egyptians rarely used it for jewellery or in its raw form. They much preferred it for its use in paint, and often painted death masks in green, inspired by the story of the god of plant life and the underworld: Osiris. Many of these masks have retained their extraordinary colour, where works even thousands of years later have not.

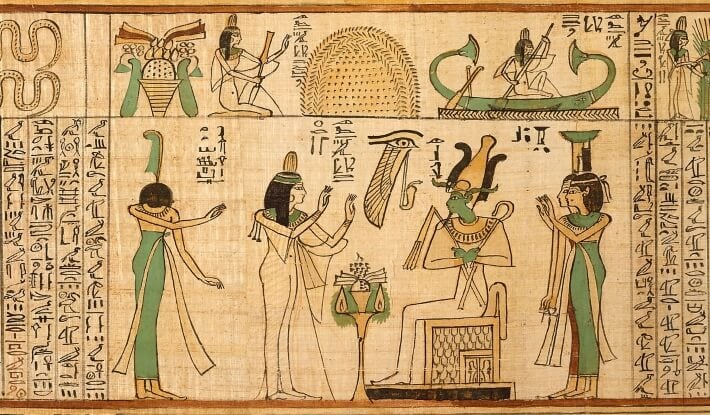

Nany Before Osiris, Isis, and Nephthys (Book of the Dead for the Singer of Amun, Nany); Painted Papyrus, c.1050 B.C., Egypt, 3rd Intermediate Period. The green areas are painted with a pigment made from malachite.

The Romans and Greeks used malachite extensively in jewellery and amulets, the Romans associating it with Juno, Queen of the Gods, and calling it the ‘peacock stone’.

In South America, meanwhile, the ancient Mayan culture also prized malachite, believing it to have important spiritual powers and properties, and the death mask of the Red Queen, a hugely important royal figure from Palenque, is entirely constructed from a mosaic of malachite pieces. The material clearly conveyed ideas of exceptional prestige and royalty.

The death mask of the 'Red Queen', from Palenque, Mexico. The mask is made from a mosaic of malachite crystals.

To this day malachite is still believed to bring good fortune and confer health benefits. While these effects naturally remain unproven, the gemstone nonetheless still carries, and will continue to confer, connotations of prosperity, abundance, life, and spiritual wisdom, as it has since the times of Ancient Egypt.

Malachite in the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and Early Modern Europe

In the Middle Ages, and into the Renaissance and subsequent centuries, malachite most commonly appears as a pigment in painting. In Renaissance Italy it was known as ‘verdetto della magna,’ or the green from Germany. This malachite was sourced from a combining of both mining, in the traditional sense, and a form of collection from waterways called natural precipitation. The exact location for this malachite remains unclear, but scholars believe it was somewhere in modern-day Slovakia.

It can be seen in artworks and paintings from the likes of Giovanni Bellini, the great Venetian master, to Raphael, in a work such as the spectacular and hugely important Sistine Madonna. The rich green colour in paintings is preserved to varying degrees of success based upon the binder and mixers used. In Bellini’s works, such as the National Gallery’s Agony in the Garden, it has unfortunately turned brown due to reactions with the sulphur within the egg-yoke binder, whereas in Raphael’s work, the rich green in the curtain and drapery elements has remained intact, largely due to the presence of lead-white in the paint mixture.

Raphael's 'Sistine Madonna,' oil-on-canvas, c.1513-14, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden. One of Raphael’s great masterpieces, the rich green comes from a mixture of malachite and orpiment.

In this period malachite was used in small amulets and jewellery, particularly for children. After the Middle Ages, and the various devastating plagues and diseases that swept across the continent, beliefs and superstitions arose that malachite provided health benefits and was able to ward off evil spirits.

Further afield, in China during the Qing dynasty, small amulets and pieces, such as snuff bottles, were made of malachite crystals, anticipating the use of malachite in more elaborate pieces in Europe by more than a century.

Some of these pieces feature a beautiful combination of malachite and azurite, a mineral very similar in composition to malachite, but of a deep blue colour instead. These minerals are often found together, and in some cases flow elegantly into each other.

Meanwhile, back in Europe, malachite was starting to be used again in the decorative arts, predominantly as a veneer or inlay, such as in Italian works in micro-mosaic and pietra dura, including those made by the Vatican Mosaic workshop in Rome. Many a table or decorative object from this time can be found with a ring or layer of malachite added to give it a wonderful flash of green.

Cameos and small amulets have since continued to be a popular medium for malachite works, the relative softness of the stone making it suitable for fine carving and details. Such examples can be found in many of the major art and archaeological museums in Western Europe.

An assortment of amulets and jewels with malachite, from the British Museum and Royal Collection. A gold and malachite cameo brooch after 'Night' by Bertel Thorvaldsen; a Qian period Chinese snuff bottle in malachite and azurite, and an Italian snuff box with a micro mosaic front panel.

Malachite Antiques in Imperial Russia c.1750 - 1917

By the 18th century, many of the traditional and oldest malachite reserves had been depleted and mined to exhaustion. One location, however, where malachite was found in vast large pieces was the Ural Mountain range in Russia. One, even two tonne blocs of malachite could be found here, a phenomenon that has not been discovered anywhere else, and for this reason, Tsarist Russia was given an extraordinary chance to build and sculpt objects in malachite in a way that no other nation or culture had before or has since.

Malachite, and malachite in antiques, will be forever connected to Imperial Russia. It is in the Tsarist court, in the nineteenth century, where malachite was most prized, and where some of the most stunning pieces and objects were crafted from this beautiful gemstone.

Corinthian columns, magnificent vases in Classical shapes and designs, entire fireplaces veneered with malachite: these are some of the fine pieces on view in locations such as the Winter Palace in St Petersburg.

Indeed, the Malachite Room in the Winter Palace, now part of the Hermitage Museum, is perhaps the most famous location of malachite antiques, and one of the most famous rooms in Russian history, closely associated with the late Tsars, and with the Russian Provisional Government in 1917.

The Malachite Room in the Winter Palace, St. Petersburg

The influence of Russia, and the growing use of Malachite across Europe

Many of the very best malachite antiques are original Russian pieces, such as a pair of vases we are privileged to house in our own collection, or works that aim to resemble these famous originals, and replicate their sense of grandeur and opulence. The enduring value of malachite antiques lies in their superb designs and sumptuous raw materials used, both malachite, and the gilt-bronze with which it is usually paired.

The Malachite Room in St. Petersburg inspired other such locations, both in France at Versailles, and as far afield as Mexico, where, as we have seen, there already existed a rich history of using this precious gemstone.

The Malachite Room in the Castillo de Chapultepec, Mexico

The Malachite Room in Versailles was previously known as the ‘Cabinet of the Sunset’ in Louis XIV’s time, and it was built for him as a retreat from the goings on at court. It came to be known as the malachite room in the time of Napoleon, after he used it to house several diplomatic gifts which he had received from Tsar Alexander I.

This collection of Russian vases and urns was added to by the work of Jacob-Desmalter, an important French maker, who embraced the use of malachite, and led to its close association with the French Empire style.

Mayfair Gallery is proud to house a pair of original Russian 'Medici' vases by I. Galberg in our collection.

Thus, the use of malachite in the decorative arts spread across Europe because of the example of locations such as the Malachite Room in St. Petersburg which other royal courts wished to copy, and through diplomatic gifts from the Tsars, especially Tsar Nicolas I, who gifted the large malachite urn in the Grand Reception Room of Windsor Castle to Queen Victoria in 1839. This monumental piece also happened to be one of the few objects to survive the fire of 1992 in situ.

The Malachite Urn in the Grand Reception Hall of Windsor Castle, a gift from Tsar Nicholas I to Queen Victoria in 1839, crafted in the familiar 'Medici' design.

As the use of malachite was adopted in France in the nineteenth century, it became clear the rich affinity malachite had with a variety of French antique styles, from Louis XVI, through to the Empire style and Egyptian revival.

Malachite appears in French vases, clocks, and items of furniture during the Louis XVI period, and as such these early items carry a great deal of rarity and value. The use and popularity of malachite grew over time, and in the nineteenth century many pieces made imitating earlier styles made use of this rich gemstone, elevating earlier designs and styles with a new-found vitality and vibrancy.

Malachite and its uses today

Original malachite antiques continue to be highly prized. Often a distinction is made between original pieces, where malachite is a somewhat rarer find, and later examples where a malachite veneer, for example, is used in replacement of an earlier material.

In a sense, such a distinction misses the appeal of this superb material. The value in a malachite antique lies in the intrinsic appeal and beauty of the material itself, the rich patterns, the rings, bands, that occur naturally, and the way it complements and elevates designs and objects in a way no other gemstone can.

Malachite is also a very popular material in luxury jewellery and for smaller decorative objects and pieces such as watch faces.

The use of Malachite imitations in modern interior design can create beautiful effects, as demonstrated here.

In the realm of interior design, malachite continues to be used in making new furniture in both traditional and contemporary styles, and indeed materials and furniture elements imitating malachite are highly sought after. The very use of decorations in imitation of the unique exquisite bands within malachite, and the very fact that beautiful, stylish, and lustrous contemporary veneers and rooms are adorned with materials aiming to replicate malachite’s unique visuals demonstrates its timeless appeal and worth.

The work of 20th century Italian designer Piero Fornasetti (1913-1988), for example, often incorporated veneers copying the natural appearance of malachite. Fornasetti created everything from cabinets and mirrors to upholstery in a faux malachite pattern, that has an almost metallic glow, and replicates the lighter, more silver shade of green that tends to be of greater purity and value.

Offering a bridge across the centuries, and a link from the very earliest days of artistic endeavours and production, malachite is a gemstone with a history like no other. Its deep green waves and bands continue to be highly sought and replicated, and an antique piece offers a unique chance to connect with designers and craftsmen from centuries past.

For malachite antiques in a vast array of styles, periods, and uses, browse Mayfair’s Gallery collection of malachite furniture, clocks and vases.